A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (82 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

The route from Matamoros through the Texas desert to San Antonio was exceptionally arduous. Fremantle might have chosen the most honorable way, but it was also the most dangerous. The law, where it existed at all, was rough and imprecise, and Fremantle was careful to travel in company. His first act on reaching San Antonio was to sell his heavy trunk, along with most of his belongings. It made him less likely to be robbed, and it was obvious he was not going to need any formal attire.

Fremantle was ninety miles from Alexandria on May 10 when he encountered a pathetic trail of refugees fleeing the city after its capture by Banks. Having grown anxious that he might become trapped on the west side of the Mississippi, he made a dash across the river. A Confederate steamboat took him part of the way, but for the final thirty miles he had to paddle upstream in a skiff with six other men. Fremantle finally reached Jackson on May 18. By now he had only a small bag and the clothes on his back. As he walked past the still smoldering Catholic church and the ruins of what had once been Jackson’s principal hotel, he fell into the hands of local vigilantes who were eager to hang someone. Fremantle was saved by an Irish doctor who pushed his way through the crowd, saying, “I hate the British Government and the English nation, but if you are really an officer in the Coldstream Guards there is nothing I won’t do for you.”

29

Once the mob was satisfied that Fremantle was not a spy, he was allowed to continue on his way. He reached General Johnston’s headquarters a couple of days after Grant’s first assault on Vicksburg. Johnston seemed a little detached: “He talks in a calm, deliberate and confident manner,” wrote Fremantle; “to me he was extremely affable, but he certainly possesses the power of keeping people at a distance when he chooses, and his officers evidently stand in great awe of him.” When Johnston told Fremantle that they had nothing compared to the Federals, the British officer realized that he was speaking the literal truth. “At present his only cooking-utensils consisted of an old coffee-pot and frying pan—both very inferior articles.” When they sat down to eat, Fremantle discovered “there was only one fork (one prong deficient) between himself and Staff, and this was handed to me ceremoniously as the ‘guest.’ ”

30

Fremantle encountered the same polite behavior wherever he went. The Confederates were curious about him, and he was constantly peppered with questions, such as whether the Coldstream Guards really wore scarlet into battle. Inevitably someone would ask him whether he thought British soldiers could fight as well or better. During one train journey there was a lively debate in the carriage as to whether the British could have defeated Lee at Fredericksburg.

It was May 28 when Fremantle arrived in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where General Bragg and his long-suffering army were encamped. He was not the only visitor at Bragg’s headquarters. The staff introduced Fremantle to an unexpected guest: three days earlier, Clement Vallandigham, the dissident Democrat and leader of the so-called Copperheads, had been unceremoniously dumped in front of Confederate pickets and ordered by his Federal guards not to turn back.

The exiled politician was outraged at his treatment by the U.S. government. On May 1 he had attended a rally in Ohio where he gave one of his usual antiwar speeches. It was a deliberate provocation, and General Burnside—who had been transferred to run the Department of Ohio, which oversaw all military matters across seven states from Wisconsin to West Virginia—fell into the trap. On May 4 Burnside sent soldiers to Vallandigham’s house in Dayton. They smashed down his back door and dragged the politician off to a waiting train. Vallandigham’s arrest had the effect that he was hoping for: newspapers throughout the Midwest declared him a martyr to free speech and freedom of conscience. Burnside hastily assembled a military tribunal of eight army officers to “try” the case. It was a farce, Vallandigham indignantly told Fremantle; one of the officers was not even American. (The unknown officer was Colonel John Fitzroy De Courcy, who had returned to duty and was anxious to be of use to Burnside in the hope it would lead to his reinstatement with the 16th Ohio.)

The tribunal listened to the evidence for two days and came to a unanimous agreement on the defendant’s guilt. They had more difficulty deciding what to do with him. One thought he ought to be shot; another suggested exile; eventually they agreed he should be imprisoned in a fort somewhere.

31

But the ensuing national uproar over Vallandigham’s trial severely embarrassed the administration, and Lincoln swiftly commuted the sentence to banishment. But Vallandigham had no more wish to be in the South than the rebels had to receive him. He had been made, in Fremantle’s words, “a destitute stranger” in his own country. General Bragg was puzzled as to how to treat his reluctant visitor; Vallandigham’s platform of compromise and reunion was no more popular in the South than Lincoln’s policy of forced reunion. He was relieved to learn that Vallandigham wished to travel to Bermuda, where it would be possible for him to take a ship to Canada. Vallandigham preferred not to mix with his hosts while they waited for permission from Richmond to allow him to travel to Wilmington. He did not consider himself a Confederate sympathizer and was not interested in meeting foreign supporters of the South; he politely declined an introduction to the sole English volunteer on Bragg’s staff.

Colonel Fremantle, on the other hand, was delighted to meet his compatriot. “Ever since I landed in America, I had heard of the exploits of an Englishman called Colonel St. Leger Grenfell,” he wrote on May 30, two days after his arrival at Bragg’s headquarters. “This afternoon I made his acquaintance, and I consider him one of the most extraordinary characters I ever met. Although he is a member of a well-known English family, he seems to have devoted his whole life to the exciting career of a soldier of fortune.” Grenfell was Bragg’s inspector general of cavalry, having left the raiding outfit led by the Confederate guerrilla John Hunt Morgan the previous Christmas. Fremantle was surprised to learn that Grenfell was fifty-five years old and that he had a wife (who had thrown up her hands some years before and was running a successful girls’ school in Paris) and two grown-up daughters.

32

Grenfell told Fremantle that he had fought the Barbary pirates in Morocco, followed Garibaldi in South America, and joined the Turks against the Russians in the Crimea. The last was undoubtedly true, as he had been Colonel De Courcy’s brigade major in the Turkish contingent.

33

Neither Grenfell nor De Courcy ever knew that their paths had again crossed during the Federal occupation of the Cumberland Gap.

“Even in this army,” wrote Fremantle,

which abounds with foolhardy and desperate characters: [Grenfell] has acquired the admiration of all ranks by his reckless daring and gallantry in the field. Both Generals Polk and Bragg spoke to me of him as a most excellent and useful officer, besides being a man who never lost an opportunity of trying to throw his life away. He is just the sort of a man to succeed in this army, and among the soldiers his fame for bravery has outweighed his unpopularity as a rigid disciplinarian. He is the terror of all absentees, stragglers and deserters, and of all commanding officers who are unable to produce for his inspection the number of horses they have been drawing forage for.

34

Grenfell always wore a red cap, which made him conspicuous in battle and therefore more esteemed among the officers.

Grenfell took Fremantle on a tour of the outposts. During the ride he was frank about the army’s deficiencies, as well as his own troubles: “He told me he was in desperate hot water with the civil authorities of the State, who had accused him of illegally impressing and appropriating horses, and also of conniving at the escape of a negro from his lawful owner, and he said that the military authorities were afraid or unable to give him proper protection.” Three days later, on June 3, “Grenfell came to see me in a towering rage,” wrote Fremantle. He had been arrested. “General Bragg himself had stood bail for him, but Grenfell was naturally furious at the indignity. But, even according to his own account, he seems to have acted indiscreetly in the affair of the Negro, and he will have to appear before the civil court next October. General Polk and his officers were all much vexed at the occurrence.

35

Bragg’s surety was misspent. A week later, Grenfell packed his bags and disappeared. No one heard anything of him for three months.

By then, Fremantle had already left for the east. After another tortuous train ride, which had the single distinguishing feature of a female soldier in their midst, he arrived at Charleston.

20.3

One of the first people to greet him was Captain Henry Feilden. Fremantle was amazed to come across another English volunteer. “A Captain Feilden came to call upon me at 9

A.M.,

” he wrote in his diary. “I remember his brother quite well at Sandhurst.”

36

The younger Feilden seemed entranced with the South. Naturally, Fremantle could not know of the momentous event that had taken place in Feilden’s life that week: Miss Julia McCord of Greenville, South Carolina, had visited the office, seeking a military pass to visit her brother.

20.1

Mrs. Chancellor and her six daughters were rescued by one of Hooker’s aides, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Dickinson. He disobeyed orders and remained with the women until they were safely across the Rappahannock, earning their eternal friendship and gratitude.

20.2

In his history of the Civil War, Winston Churchill wrote: “Chancellorsville was the finest battle which Lee and Jackson fought together. Their combination had become perfect.”

14

20.3

While Fremantle was in Charleston, the local newspapers reported: “The Western army correspondent of the ‘Mobile Register’ writes as follows:—‘The famous Colonel St. Leger Grenfell, who served with Morgan last summer, and since that time has been Assistant Inspector-general of General Bragg, was arrested a few days since by the civil authorities.… If the charges against him are proven true, then there is no doubt that the course of General Bragg will be to dismiss him from his Staff; but if, on the contrary, malicious slanders are defaming this ally, he is Hercules enough and brave enough to punish them. His bravery and gallantry were conspicuous throughout the Kentucky campaign, and it is hoped that this late tarnish on his fame will be removed; or if it be not, that he will.’ ”

TWENTY-ONE

The Eve of Battle

A message to the shipbuilders—British reaction to Jackson’s death—Henry Hotze resurgent—All eyes on Lee—Sir Percy Wyndham finds glory at Brandy Station—A lost boy

“M

y father heard about your going out to America to see me,” the Marquis of Hartington wrote to Skittles after his return to London in early spring. “He has been told all about the whole thing, which he had no notion of before [and] is in a terrible state about it.” He added disingenuously: “I told him you had given me up and he knows that I am very unhappy.” The truth, as they both knew, was that he was gently putting his mistress aside, or at least was trying to, with so far limited success.

1

Yet Hartington would not have the luxury of dithering for much longer; he had received an invitation from Lord Palmerston to join the government, which would mean assuming greater responsibilities while enjoying fewer of life’s pleasures. “I think it would be a most horrible nuisance,” he wrote.

2

On April 13, 1863, however, the decision was made for Hartington by the unexpected death of George Cornewall Lewis, the secretary for war.

21.1

Earl de Grey was promoted from undersecretary to secretary, and Hartington was offered de Grey’s former position, an honor not even he could refuse.

3

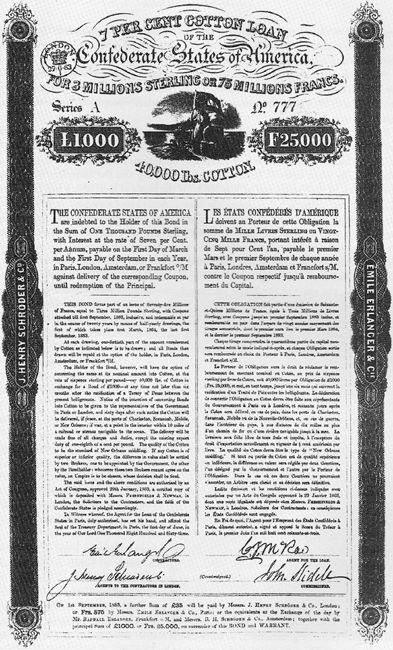

Ill.39

A certificate for the 7 Per Cent Cotton Loan, signed by Emile Erlanger and J. Henry Schroeder, and by Colin McRace and John Slidell for the Confederacy.