A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (97 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

The imminent arrival of more Confederate troops renewed Bragg’s confidence. A battle was imminent, but he would no longer be fighting a numerically superior enemy. Rosecrans had divided his army into three isolated forces. If Bragg could lure each of them in turn into one of the deep valleys that marked the terrain around Chattanooga, he might be able to destroy the entire Federal army. His plan depended on General Burnside’s remaining in Knoxville, and on his own generals’ following his exact orders. Burnside obligingly fiddled and fussed, but Bragg’s second requirement proved to be impossible. The Confederate commander had made himself so despised that his generals ignored him, allowing opportunities to attack to slip through their grasp. Bragg desperately needed Longstreet, if only to restore order and spirit to his army.

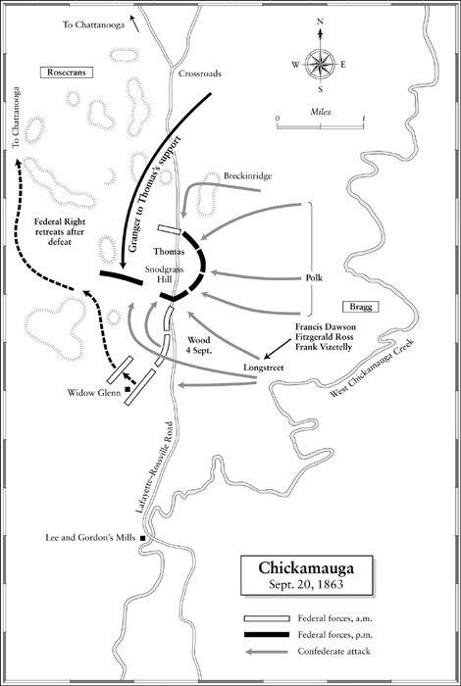

When news of Longstreet’s departure for Tennessee reached Charleston, Frank Vizetelly and Fitzgerald Ross took the first available train to Georgia, accompanied by a British Army officer named Charles H. Byrne, who had run the blockade in order to join the staff of the renowned Irish Confederate general Patrick Cleburne. The travelers arrived in Augusta on September 15. The town owed its prosperity to the Savannah River; “most of the goods which run the blockade into Charleston and Wilmington are sold by auction here, whence they are dispersed all over the interior,” reported Ross, whose appetite for running after the action remained strong despite the misery of Gettysburg. “We found several English friends in Augusta engaged in the blockade-running business.” An invitation to stay proved too tempting to resist, and the three companions had such a merry time that they were caught by surprise when Longstreet’s train passed through on September 19. Realizing that they were in danger of missing the battle, they begged a ride on the next train. On the twentieth they lurched to a halt outside Ringgold, several miles south of Bragg’s army, unable to travel any farther because of broken track. It was obvious from the crowded pens of Federal prisoners in the middle of the town that the battle for east Tennessee had already begun.

Longstreet arrived at Bragg’s headquarters near the Chickamauga River (“River of Death” in Cherokee) just before midnight on September 19; the bulk of his troops were with him, although the artillery train carrying Francis Dawson was still en route. Bragg had mismanaged the first day of fighting, making uncoordinated attacks that were readily crushed by the Federals. For the morrow, he told Longstreet, the army was to be divided into two, with Longstreet commanding one wing and General Bishop Leonidas Polk the other, in order to hit Rosecrans in synchronized blows, left and right.

16

The blows did take place, but, because of a combination of undelivered orders, misunderstood directions, and the difficulty of operating in a thickly wooded terrain that screened parts of the fighting, the synchronization did not. Even so, Longstreet was magnificent. While Bragg was panicking and calling the battle lost, “Old Pete” realized that the Federal line had split and sent in his wing to exploit the opportunity. The Confederates almost succeeded in breaking Rosecrans’s entire army. But one U.S. general, George H. Thomas—who was henceforth known as “the Rock of Chickamauga”—held his position and prevented a total Federal disaster.

It was late afternoon when Vizetelly and Ross heard about Longstreet’s assault. Vizetelly wanted to rush to the front, appalled that he was missing the battle. They did not arrive at Longstreet’s camp until evening: “We had walked a dozen miles,” wrote Ross, “and, not knowing where to find our friends, we concluded to stay where we were all night.” They had missed one of the most dramatic and bloody days of the war. Longstreet’s attack had spread mass panic among his opponents, reminiscent of the Federal flight during the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Rosecrans’s army, and indeed Rosecrans himself, had fled to Chattanooga, leaving the Confederates in possession of his deserted headquarters. As soon as it was light, the companions resumed their search for Longstreet. “We had been very much disappointed at being too late for the battle,” wrote Ross, “but I think what we saw today rather moderated our regret.” In all, 36,000 men had been killed or wounded during the two-day fight, nearly a third of the total who had taken part. During the night, while Ross and Vizetelly slept, the battlefield had been a hive of activity as small details of soldiers and civilians searched for survivors, holding their lanterns aloft to avoid treading on hands and feet.

Map.17

Chickamauga, September 20, 1863

Click

here

to view a larger image.

The Confederate private Sam Watkins had helped to carry the wounded to the field hospitals. “Men were lying where they fell, shot in every conceivable part of the body,” he wrote afterward. “Some with their entrails torn out and still hanging to them and piled upon the ground beside them, and they were still alive.” He passed a group of women who had been looking for relatives. One of them cradled a dead soldier’s head on her lap, crying, “My poor, poor darling! Oh, they have killed him, they have killed him!” He turned away, but there was nowhere to look without being assaulted by gore and terror. A man whose jaw had been torn away, leaving his tongue lolling from his mouth, tried to talk to him. Another stumbled past with both his eyes shot out, though one was still hanging down his check. “All through that long September night we continued to carry off our wounded,” he recorded.

17

Bragg was transfixed by the bloodshed. Longstreet argued, even pleaded with him to be allowed to launch another attack on the Federals before they had time to fortify Chattanooga and briefly thought he had persuaded the general to follow up his victory. But Bragg saw the thousands of corpses, the dead horses and shattered wagons, and despaired. He ordered the entire army to take up a new position along the crest of Missionary Ridge, which overlooked Chattanooga. Rather than endure another battle, he planned to starve Rosecrans into surrender, just as Grant had done to the Confederates at Vicksburg. Vizetelly and Ross realized that they were in the midst of an uproar in the camps and that the troops were furious with their leader. “I do not know what our Generals thought,” wrote Sam Watkins. “But I can tell you what the privates thought.… We stopped on Missionary Ridge, and gnashed our teeth at Chattanooga.”

18

Watkins would have been gratified to know that Bragg’s commanders shared his outrage. Several of them were discussing with Longstreet whether they should risk their careers by sending an official complaint to Richmond.

Vizetelly was circumspect in his report of the Battle of Chickamauga for the

Illustrated London News.

He made no mention of the generals’ revolt against Bragg, or that Longstreet was leading the cabal.

19

His shame at having arrived late may have pushed him to exceed his usual exuberance in camp. Every night he sang songs and entertained the senior officers as though his life depended on their enjoyment. The Confederates were mystified by their riotous visitor who could drink them all under the table, but were deeply appreciative of his efforts. “It was no uncommon thing to see a half dozen officers, late at night, dancing the ‘Perfect Cure’ which was one of the favorite songs … in the London music halls, and was introduced to our notice by Vizetelly,” wrote Francis Dawson, who was thrilled to share his tent with him.

20

Years later, Longstreet’s artillery chief, Edward P. Alexander, could still remember Vizetelly teaching them the words to “Tiddle-i-wink.”

25.1

“He was really a man of rare fascination and accomplishments,” reminisced Alexander. “He made great friends everywhere, but especially in Longstreet’s corps.”

21

The evening frolics could not mask the fact that the Confederate Army of Tennessee was in crisis. Bragg had suspended two popular generals, Bishop Leonidas Polk and Thomas Hindman, for their failure to carry out his orders during the battle. Longstreet had secretly sent an official complaint to Richmond against Bragg and was waiting for a reply. The fourteen other senior generals were on edge, as Francis Dawson discovered. He had been made acting chief of ordnance while his superior, Colonel Peyton T. Manning, recovered from a head wound, and his temporary promotion gave him a seat at the staff dinners. One night, Major Walton,

who I had always disliked heartily [wrote Dawson], said that when the Confederate States enjoyed their own government, they did not intend to have any damned foreigners in the country. I asked him what he expected to become of men like myself, who had given up their own country in order to render aid to the Confederacy. He made a flippant reply, which I answered rather warmly, and he struck at me. I warded off the blow, and slapped his face.

The next morning, Dawson asked Ross to deliver his challenge to Major Walton. Ross had relished the prospect of a duel, but he was deprived of the spectacle by Walton’s offer of a written apology. Dawson waited for two days. When none came, he sent Ross to see Walton again. The major informed him that he had changed his mind. Delighted, Ross responded that the major must choose his weapons, since the challenge still held. “This brought Walton to terms,” wrote Dawson, “and he made the apology I required.”

22

Dawson felt vindicated, but he still had to dine with Walton every day.

The tensions in Bragg’s army increased until, on October 5, twelve generals signed a petition asking for him to be removed from his command. Francis Lawley hoped that Longstreet would take over from General Bragg. “I have done my very utmost to get him to the helm,” he wrote to a friend. “The disappointment and indignation of his own corps, if he is put under Bragg, will be great and dangerous.”

23

Lawley was still feeling weak as well as unappreciated by his employers; he had recently received a reprimand from Mowbray Morris at

The Times,

who, in a momentary pang of editorial responsibility, had asked him to tone down his “extravagant partiality to the Southern Cause.”

24

Lawley arrived from Richmond just as Bragg learned of the attempted coup against him. He was unsurprised by the “heartburning recrimination” that had infected all ranks of Bragg’s army.

25

When Jefferson Davis arrived at the camp on October 9, Lawley assumed that the president had made the difficult journey expressly to remove the unpopular general. “The conclusion is irresistible,” Lawley told

Times

readers in his new spirit of semi-impartiality, “that General Bragg failed to convert the most headlong and disordered rout which the Federals have ever seen … into a crowning victory like Waterloo.” Cold, driving rain accompanied Davis’s visit. Francis Dawson had to dig a trench around their tent to keep the water from flooding in during the night. The rain did not deter wild hogs from feeding on the dead, but most other activity ceased. The guns could not be moved, as the wagons became stuck. “Few constitutions can stand being wet through for a week together,” wrote Ross. They were fortified, however, by the box of provisions Lawley had brought with him from Virginia. He had also arrived with a spare horse, which enabled the observers to follow President Davis as he visited the different headquarters. Davis stayed for five days, and every day the generals, the travelers, indeed the entire army, expected an announcement.

—

On September 22, 1863, the telegraph office in Washington had erupted into frenzied activity as the first reports came through from Chickamauga. The message from General Rosecrans was blunt: “We have met with a serious disaster.”

26

The news was bewildering to the cabinet. Their most recent message from Rosecrans had announced his effortless capture of Chattanooga. Although Lincoln and General Halleck had been concerned that General Burnside was taking too long to march from Knoxville to join forces with Rosecrans, it had never occurred to them that the Army of the Cumberland was in any real danger from Bragg. Tennessee had appeared to be falling like a neat row of dominoes, especially now that the Gap was in Federal hands. Indeed, Lincoln was so confident that he had started to make plans to strengthen Tennessee’s pro-Northern state government.

27

The rest of the cabinet had shared Lincoln’s optimism. William Seward had been feeling sufficiently cheerful to allow his work to be interrupted by a visit from Leslie Stephen. The Englishman had arrived in Washington with a letter of recommendation from John Bright. The future editor of the

Dictionary of National Biography

(and father of Virginia Woolf) was, at the age of thirty-one, entering the final months of his career as an Anglican clergyman. Recently, Stephen had suffered a crisis of faith and was on the verge of leaving the Church and his academic post at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. His wild red hair and unkempt beard made him an alarming figure, but his combination of being a friend of John Bright and the cousin of the pro-Northern journalist Edward Dicey overcame Seward’s resistance. He invited Stephen to accompany him to the White House. A cabinet meeting was slated to begin in half an hour, but in the intervening time Seward introduced Stephen to Lincoln as a friend of the “great John Bright.” “Bright’s name is a tower of strength in these parts,” Stephen wrote in surprise to his mother: