A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (11 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

How could Russia

not

help Serbia? Nicholas was being told that his people would not tolerate another abandonment of their brothers, the South Slavs. Russia would be disgraced, would have no more friends in the Balkans, no respect in Europe. A failure of such magnitude might trigger a revolution worse than the one in 1905.

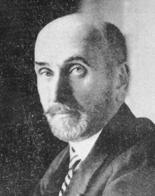

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov

“The curses of the nations will be upon you.”

One solution suggested itself. If Russia showed enough firmness, perhaps Austria would hold back. By Friday, July 24, the day after the delivery of Austria’s note, the day before Serbia was supposed to reply, Sazonov was telling the Russian army’s chief of staff to get ready for mobilization.

It was at this point that the Balkan crisis became a European one.

Background

THE HOHENZOLLERNS

THE FLAMBOYANT AND ERRATIC KAISER WILHELM II OWNED

and loved to show off more than three hundred military dress uniforms. He would cheerfully change his costume a dozen or more times daily. One of the jokes that made the rounds in Berlin was that the kaiser wouldn’t visit an aquarium without first putting on admiral’s regalia, or eat a plum pudding without dressing as a British field marshal. He really could be almost that childish, even in 1914, when he was in his early fifties and had ruled Germany for a quarter of a century. Not surprisingly, many of the men who were sworn to serve him regarded him not just as immature but as mentally unstable.

Wilhelm was only the third member of the Hohenzollern family to occupy the throne of Imperial Germany; the second had been kaiser for only months. The Hohenzollerns, unlike the Hapsburgs, were in 1914 a still-rising family at the top of a rising nation. Despite interruptions that at times had brought them to the brink of ruin, they had been rising for five hundred years, slowly emerging from obscurity in the late Middle Ages and eventually surpassing all the older and grander dynasties of Europe. They had always been more vigorous than the Hapsburgs, more warlike, rising through conquest and ingenuity rather than through matrimony. They had a remarkable history not just of ruling countries but of inventing the countries they wanted to rule. It is scarcely going too far to say that the Hohenzollerns—assisted, of course, by their brilliant servant Otto von Bismarck—invented modern Germany. Centuries earlier they had invented Prussia, a country so completely artificial that at the end of World War II it would simply and forever cease to exist.

The first Hohenzollern of note was one Count Friedrich, a member of the minor nobility who in the early fifteenth century somehow got the Holy Roman emperor to appoint him Margrave of Brandenburg, an area centered on Berlin in northeastern Germany. In his new position Friedrich was an elector, one of the hereditary magnates entitled to choose new emperors. His descendants increased their holdings during the next century and a half, expanding to the east by getting possession of a wild and backward territory called Prussia.

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Still immature after a quarter-century on the throne.

Inhabited originally by Slavs rather than by Germans, Prussia had been conquered and Christianized in the 1200s by a military religious order (there were such things in those hard days) called the Teutonic Knights. It happened that, when the Protestant Reformation swept across northern Germany, the head of the Teutonic Knights was a member of the Hohenzollern family, one Albert by name. In 1525 this Albert did what most of the nobles in that part of Europe were doing at the time: he declared himself a Protestant. Simultaneously he declared that Prussia was now a duchy, and that he—surprise—was its duke. This Albert of Hohenzollern’s little dynasty died out in the male line after only two generations, at which point a marriage was arranged between the female heir and her cousin, the Hohenzollern elector of Brandenburg. (The Hapsburgs must have nodded in approval.)

The first half of the seventeenth century was a low point for the family: Brandenburg found itself on the losing side in a North European war and for a while was occupied by Sweden. Better times returned with Friedrich Wilhelm, called the Great Elector, who was margrave from 1640 to 1688 and originated the superbly trained army that forever after would be the Hohenzollern trademark and would cause Napoleon to say that Prussia had been hatched out of a cannonball. Friedrich Wilhelm made Brandenburg the most powerful of Germany’s Protestant states, second only to Catholic Austria to the south.

In 1701 the Hapsburg Holy Roman emperor found himself in a struggle over who would inherit the throne of Spain. He needed help—he needed the tough little army of Brandenburg. The Hohenzollern elector of the time, another Friedrich (the Hohenzollerns rarely went far afield in naming their sons), wanted something in return: he wanted to be a king. This presented difficulties, but the emperor’s need was real and so things were worked out. He decided that Friedrich could have a kingdom, in a way, but that the intricate rules of imperial governance required calling it Prussia rather than Brandenburg. The rules required also that, although Friedrich could not be king of Prussia, it would be acceptable for him to style himself king in Prussia. This was nearly the feeblest way imaginable of being a king, one that made Friedrich’s new status seem faintly ridiculous. But it was a step toward real kingship, and Friedrich settled for it. He became King Friedrich I, the first Hohenzollern to be a monarch, if only in a way.

It was not until two generations later that the Hohenzollerns became kings of Prussia. This happened during one of the most remarkable reigns in European history, that of Friedrich II, who by the age of thirty-three was known to all of Europe as Frederick the Great.

Frederick the Great is too big a subject to be dealt with in a few paragraphs. Suffice it to say that he was a writer, a composer of music that is still performed today, and a “philosopher king” according to no less a judge than Voltaire (who became his house guest and stayed so long that the two ended up despising each other). He was the first monarch in all of Europe to abolish religious discrimination, press censorship, and judicial torture. He was also a ruthless adventurer all too eager for glory, and he and his kingdom would have been destroyed except for the lucky fact that, in addition to all his other gifts, Frederick happened to be a military genius. In the course of his long life he teetered more than once on the brink of total failure—at one point he was at war with Austria, France, Russia, and Sweden simultaneously—but after any number of hair-raising escapes he raised Prussia to the ranks of Europe’s leading powers. He made the Hohenzollerns one of the leading dynasties of Europe despite never having—and giving no evidence of ever wanting—children of his own. When he died in 1786, just before the French Revolution, the crown passed to an untalented nephew.

The wars of Napoleon undid all of Frederick’s achievements. They reduced Prussia first to a state of collapse, then to submissive vassalage to France. By piling humiliations upon all the German states, however, Napoleon ignited German nationalism. This led to an uprising after Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia. The Prussian army, lethal as always, contributed significantly to the defeat of the French first at Leipzig and finally at Waterloo. Hohenzollern princes were conspicuous on the field of battle; one of them was killed leading a cavalry charge. In 1815 the Congress of Vienna restored Prussia to major power status but in a new way: some of the kingdom’s easternmost holdings were given to Russia and Austria and replaced with others in the west. Prussia thus became the only major power almost all of whose subjects were German. This was important at a time when nationalism was starting to be a powerful political force, and when Germans everywhere were beginning to talk of unification. The big question was whether there would be a Greater Germany led by Austria or a Lesser Germany from which Austria, with its millions of non-German subjects, would be excluded.

The century following the defeat of Napoleon brought triumph after triumph to the Hohenzollerns. In 1864, guided by Bismarck, Prussia took the disputed but largely German provinces of Schleswig and Holstein from Denmark. Two years after that it fought Austria and won so conclusively as to put its claim to leadership among the German states beyond challenge. The Hohenzollern realm now stretched across northern Germany all the way to the border with France and included two-thirds of the population of non-Austrian Germany. In 1870 the French emperor Napoleon III, in trouble politically and desperate to find some way of reversing his fortunes, was seduced by Bismarck into committing the folly of declaring war. Prussia and the German states allied with it—Austria emphatically not included—were more than ready. They astonished the world by demolishing the French army at the Battle of Sedan. In the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, the assembled German princes declared the creation of a new German empire, a federation within which such states as Baden, Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg would continue to have their own kings but over which there would now be a Hohenzollern emperor.

As part of the spoils of war, the German princes wanted to take from France—to take

back

from France, they would have said—the province of Alsace and part of the province of Lorraine. This territory was not of tremendous importance economically or in any other real way, but many Germans believed it had been stolen by Louis XIV two centuries before and was German rather than French. Bismarck, architect of everything Prussia had achieved over the preceding decade, foresaw that France would never forgive the loss. He predicted that to keep what it had won, Germany would have to fight another war after a half-century had passed. He was right, as usual, but made no serious effort to block the annexation.

The first ruler of the newly united Germany, King Wilhelm I of Prussia, proved to be surprisingly unhappy about his elevation, even sullen. In his opinion being King of Prussia was as great an honor as any man could ever want. But an empire required an emperor, and he had no choice but to agree. He remained King of Prussia while assuming his new title, however, and Prussia continued to be a distinct state with its own government and military administration. It continued to be dominated by a centuries-old Prussian elite, the Junkers, whose sons went into the army and the civil administration and swore loyalty not to their country but to its king.

At that point, 1871, the Hohenzollerns stood at the pinnacle of Europe. Kaiser Wilhelm I, a man so stolid and methodical that the people of Berlin learned to set their watches by his appearances at his window, ruled what was unquestionably the most powerful and vigorous country in Europe. And he had a worthy heir: his son, Crown Prince Frederick, an able, conscientious, and loyal young man who in the centuries-old tradition of his family had led armies through all the great campaigns leading up to the creation of the empire and had been rewarded with the Iron Cross and a field marshal’s baton. The crown prince was happily married to the eldest and best-loved daughter of England’s Queen Victoria. She was a serious-minded young woman who had won her husband over to the idea of one day, after they had inherited the throne, transforming Germany into a democratic monarchy on the British model. Together, meanwhile, they were producing yet another generation of Hohenzollerns. Their eldest child was a boy who bore his grandfather’s name. He had a withered, useless left arm—a troubling defect in the heir to a line of warrior-kings—but he was healthy otherwise and not unintelligent. When his grandfather became emperor, the boy Wilhelm was twelve years old, his father barely forty. But only seventeen years later, filled with insecurities but determined to prove himself a mighty leader, a worthy All-High Warlord, this same boy would ascend to the throne as Wilhelm II.

Chapter 4