A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (6 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

House would depart for home having accomplished essentially nothing. He returned to an America that appeared to be on the verge of war with Mexico (U.S. troops had forcibly occupied the coastal town of Veracruz in April), was embroiled in violent labor disputes (also in April, Wilson had sent troops to Colorado to crush a strike by coal miners), but was as confident as the president of its uniquely virtuous, uniquely pacific role in the world. William Jennings Bryan, Wilson’s secretary of state, saw it as “the imperative duty of the United States…to set a shining example of disarmament.” In January the influential

Review of Reviews

had confidently told its readers that “the world is moving away from military ideals; and a period of peace, industry and world-wide friendship is dawning,” while statesman and Nobel Peace Prize winner Elihu Root wrote unhappily that, even for educated Americans, “international law was regarded as a rather antiquated branch of useless learning, diplomacy as a foolish mystery and the foreign service as a superfluous expense.”

None of these people had even the faintest idea, as June ended, of what lay just head. But they are hardly to be blamed. What was coming was unlike anything anyone had ever seen.

Background

THE SERBS

NO ONE COULD HAVE BEEN SURPRISED THAT TROUBLE

had broken out in the southeastern corner of Europe, or that the Serbs were at the center of that trouble. In 1914, as before and since, the Balkan Peninsula was the most unstable region in Europe, a jumble of ill-defined small nations, violently shifting borders, and intermingled ethnic groups filled with hatred for one another and convinced of their right to expand. By 1914 the Balkans were exploding annually. The little Kingdom of Serbia, seething with resentment and ambition, was never not involved.

The roots of the trouble went deep. Almost two millennia ago the dividing line between the Eastern and Western Roman Empires ran through the Balkans, and so the dividing line between the Catholic and Orthodox worlds has run through the region ever since. Later, after the Turks forced their way into Europe, the Balkans became another of the things it continues to be today: the home of Europe’s only indigenous Muslim population, the point where European Christendom ends and Islam begins. Through many generations the Balkans were a prize fought over by Muslim Turkey, Catholic Austria, and Orthodox Russia. By 1914, Turkey having been pushed almost entirely out of the region, the contest was between Russia and Austria-Hungary only, with Turkey waiting on the sidelines in hope of recovering some part of what it had lost.

The Russians wanted Constantinople above all. In pre-Christian times it had been the Greek city of Byzantium, and it then became the Eastern Roman capital until falling to the Turks. It dominated the long chain of waterways—the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus—that linked Russia’s Black Sea ports to the Mediterranean. Possession of Constantinople would make the tsar—the word means “caesar” in Russian, as does kaiser in German—what Russia’s rulers had long claimed to be: rightful leader of the whole Orthodox world, rightful heir to the old eastern empire. It was largely with Constantinople in mind that the Russians anointed themselves patrons and protectors of the Slavic and Orthodox populations in the Balkans, the Serbs included. As the nineteenth century unfolded and the Turkish empire entered a terminal state of decay, it was mainly Britain that kept the Russians from seizing Constantinople. The British were motivated not by any affection for the Turks but by simple self-interest. They feared that Russian expansion to the south would threaten their own position in the Middle East and ultimately their control of India.

The Serbs had been part of a wave of so-called South Slavs (Yugoslavs, in their language) that moved into the Balkan region during the seventh century, when the Eastern Roman Empire was beginning to totter (Rome itself had collapsed much earlier) and many tribal groups were on the move. In the centuries that followed, the Serbs built a miniature empire under their own tsar. For a time it was uncertain whether all the Serbs would be Orthodox or some would be Roman Catholic, but eventually they settled into the Orthodox faith. Thereby they helped to ensure that a thousand years hence their descendants would identify themselves with the greatest of Slavic and Orthodox nations, Russia, and would look to the Russians for protection. They assured also that religious differences would contribute to separating them from Catholic Austria and from the Magyars (many of them Calvinist Protestants) who dominated Hungary.

From the late Middle Ages, in the aftermath of their defeat at Kosovo, the Serbs were trapped inside the empire of the Ottoman Turks. By the eighteenth century the Turks, the Austrians, and the Russians were entangled in what would turn into two hundred years of bloody conflict in and over the Balkans. In 1829 a Russian victory over the increasingly incompetent and helpless Turks made possible the emergence of a new principality that was, if almost invisibly tiny, the first Serbian state in almost half a millennium and a rallying point for Serbian nationalism. In the 1870s another Russo-Turkish war broke out, with Serbia fighting actively on the side of Russia this time and gaining more territory as a result. Now there was once again a Kingdom of Serbia, a rugged, mountainous, and landlocked little country surrounded by the whole boiling ethnic stew of the Balkans. Its neighbors were Europe’s only Muslims, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians some of whom thought of themselves as Serbs and some of whom did not. Among those neighbors were Magyars, Bulgars, Croats, Albanians, Macedonians, Romanians, Montenegrans, Greeks, and—just across the border in Bosnia—brother Serbs suffering the indignity of not living in Serbia. Despite the inconvenient fact that Serbs were only a minority of the Bosnian population (fully a third were Muslims, and one in five was Croatian and therefore Roman Catholic), the incorporation of Bosnia into an Orthodox and Slavic Greater Serbia became an integral part of the Serbs’ national dream. The fact that under international law Bosnia was the possession of two of the great powers—officially of the Ottomans but actually of the Austrians in recent years—mattered to Serbia not at all.

As the years passed, trouble erupted with increasing frequency, and sometimes with shocking brutality. At the start of the twentieth century Serbia had a king and queen who were friendly to Hapsburg Vienna. In 1903 a group of disgruntled army officers staged a coup, shot the royal pair to death, threw their naked bodies out the windows of their Belgrade palace, and replaced them with a dynasty loyal to Russia.

In 1908 Austria-Hungary enraged Serbia by annexing Bosnia and the adjacent little district of Herzegovina, taking them from the Ottoman Turks and making them full and presumably permanent provinces of the Hapsburg empire. Serbia turned to Russia for help. The Russians, however, were still recovering from a 1905 war with Japan in which total and humiliating defeat had exposed the incompetence of both their army and their navy, forced the abandonment of their ambitions in the Far East, and ignited a revolution at home. As a result—and to its further humiliation—the Russian government felt incapable of doing anything to support the Serbs.

In 1911 the same conspirators who had murdered Serbia’s royal family founded Union or Death, the Black Hand. Then in 1912 came the First Balkan War. Serbia joined with several of its neighbors to drive the Turks all the way back to Istanbul. The victory doubled the kingdom’s size and raised its population to four and a half million. A year later, in the Second Balkan War, Serbia defeated its neighbor and onetime ally Bulgaria. Again it grew larger, briefly seizing part of the Dalmatian coast but being forced to withdraw when the Austrians threatened to invade. Serbia was still getting not nearly as much support as it wanted from Russia, but France, seeing a strategic opportunity in the Balkans, was now providing money, arms, and training to the Serbian army. France’s motives were transparent: to make Serbia strong enough to tie up a substantial part of the Austro-Hungarian army in case of war, so that France and its ally Russia (and Britain too, if everything went perfectly) would be free to deal with Germany alone.

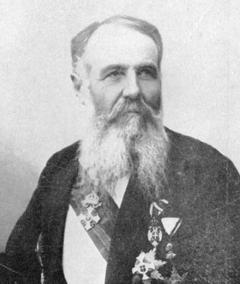

To what extent did the government of Serbia know in advance of the plot to kill Franz Ferdinand? To what extent could Belgrade therefore be held responsible? As with many parts of this story, the answer is neither clear nor simple. Prime Minister Nikola Pasic, a shrewd old man with a majestic white beard, did hear about the plot weeks before the shooting, but he emphatically disapproved. He put out the word on the Belgrade grapevine that the plot should be called off. On the other hand, Serbian officialdom was not entirely innocent. The leader of the Black Hand was the country’s chief of military intelligence, one Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijevic, a monomaniacally dedicated Pan-Serb nationalist whose physical strength had caused him to be nicknamed “Apis” after a divine bull in ancient Egyptian mythology. Apis had been the mastermind behind the strategy that led to Serbia’s successes in the Balkan wars. Now, in 1914, he was the mastermind behind the plot to kill Franz Ferdinand. But there has never been any evidence that Pasic’s cabinet was involved.

Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pasic

“Our cause is just. God will help us.”

On the contrary, Apis and his allies in the Black Hand and the military saw Pasic as an obstacle, even as an enemy. The prime minister’s lack of enthusiasm for extreme measures, for another round of war, was contemptible in their eyes. Pasic was so unacceptable to the Serbian army’s high command that in June 1914 the generals forced him out of office. He was almost immediately restored, but only at the insistence of the Russians and the French, who regarded him as sane and sensible and therefore as a badly needed man in the Balkans. Pasic’s return to office was a defeat for Apis, an indication that his influence was waning. Apis may have seen the assassination of Franz Ferdinand as a way of precipitating a crisis that would cause Pasic’s government to fall, and if the crisis led to war, he would not have been likely to regard that as too high a price to pay. Pasic, on the other hand, understood that Serbia was physically and financially exhausted after two wars in as many years—its casualties had totaled ninety thousand, an immense number for such a small country—and that the army was in no condition to challenge the Austrians. In case of war, Serbia would be able to muster only eleven badly equipped divisions against Vienna’s forty-eight. And of course Pasic was mindful of Russia’s failure to come to Serbia’s aid in 1908, in 1912, and again in 1913.

Why didn’t Pasic intervene more actively to stop the assassination? Actually, he went so far in that direction as to put himself at risk. He sent out an order that the three conspirators whose names had become known to him should be stopped from crossing the border into Bosnia. But the answer came back that he was too late—the three were already across. He then directed his ambassador in Vienna to deliver an oral warning. But this ambassador, himself an ardent Serb nationalist, had no great enthusiasm for such a mission. He met with Austria’s finance minister rather than with someone better positioned to take action on such a matter. He expressed himself so vaguely—he said he was concerned that “some young Serb might put a live rather than a blank cartridge in his gun, and fire it,” never indicating that Belgrade had knowledge of an actual plot and even knew the names of conspirators already in Sarajevo—that the finance minister could see no reason for alarm and was given no basis on which to do anything. It must have seemed to Pasic, who could have known nothing of how his warning had been diluted, that there was nothing more he could do. That summer Serbia was in the midst of an election. The result would decide whether Pasic remained as prime minister. It would have been suicide, certainly politically and perhaps literally, for him to become known as the enemy—the betrayer, even—of the most violently passionate patriots in the kingdom.

By then no one but the assassins themselves could have stopped the assassination. Not even the Black Hand, not even Apis himself, was now in control. On June 14 Apis told a meeting of the Black Hand executive committee of his plans for Sarajevo in two more weeks. The committee’s members did not react as he expected. They voted that the plot must be called off. Like Pasic, they realized that the assassination could lead to war with the empire next door, and undoubtedly they understood that the prime minister had reason to be opposed. Apis, through a chain of intermediaries, managed to get word to the assassination gang to abandon its plot. Now it was his turn to be ignored. Gavrilo Princip, in an interview with a psychiatrist as he lay dying of tuberculosis in an Austrian prison midway through the war (an interview in which, strangely, he often spoke of himself in the third person), would say that in going to Sarajevo “he only wanted to die for his ideals.” He had been happy to accept the Black Hand’s weapons but unwilling to obey when instructed not to use them.

Chapter 2