A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (4 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

Smith-Dorrien, Horace.

Corps and army commander with British Expeditionary Force, August 1914–May 1915

Stopford, Frederick.

Commander of the landing force at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, August 1915

Stürmer, Boris.

Russian prime minister, February–November 1916; also served as interior minister and foreign minister

Sukhomlinov, Vladimir.

Russian war minister, 1909–15

Tirpitz, Alfred von.

Prussian naval minister, 1897–1916

Tisza, István.

Prime Minister of Hungary, 1913–17

Trotsky, Leon.

Leading member of Bolsheviks; principal political adviser to Lenin; head of Russian delegation to Brest-Litovsk negotiations

Viviani, René.

Premier of France, June 1914–October 1915

Wilhelm, Crown Prince.

Eldest son and heir of Wilhelm II; commander of the German Fifth Army from August 1914 and of an army group from September 1916

Wilhelm II.

Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia, 1888–1918

Wilson, Henry.

Britain’s military liaison with France; chief of the imperial general staff from March 1918

Wilson, Woodrow.

U.S. president, 1913–21

Zimmermann, Arthur.

German deputy foreign minister

Introduction

T

his book is a labor of love. It has grown out of a lifelong fascination with the war that George F. Kennan called “the great seminal catastrophe”—the one out of which a century of catastrophes arose.

My fascination began when, as a boy of twelve or thirteen, I came into possession of a paperback copy of Erich Maria Remarque’s

All Quiet on the Western Front

. I remember being unable to put it down—even taking it with me to the ballfield, where I could return to it on the bench when my side was at bat. I remember reading some of its more lurid descriptions of life in the trenches aloud to my pals and then to my mother, who, horrified, ordered me to stop.

It was not until twenty years later, when I made two long camping trips through Europe, that the immensity of the tragedy that was the Great War became clear to me. Nearly every village and church in Austria, Britain, France, and Germany has its First World War memorial, and their lists of the dead seem impossibly long. Everywhere I went the question was the same: how could so small a place have lost so many boys and men? My curiosity grew. My reading, untainted by any thought that I might one day undertake to write about what I was learning, broadened.

Years passed, and I gradually became aware that I had never found a one-volume history of the war that seemed to me entirely satisfactory. It hardly need be said that the number of fine works on the subject is very, very large. Among these works are brilliant scholarly accounts of how the war erupted when it did in spite of the fact that almost no one wanted it, why it went on year after year as European civilization slipped toward collapse, just how vast a calamity it was, and the terrible things that came in its wake. Some of these books are almost above criticism. Few of them even attempt to appeal to the general reader.

There are also, of course, many admirable popular histories. Some are about specific aspects of the war (one of its years, fronts, battles); some embrace the entire conflict. That even the broadest leave out important things is not only unsurprising but inevitable—no one knows better than I now do that no narration confined within a single pair of covers can deal with

everything

. Still, I never found a work without gaps that struck me as unnecessary and regrettable, or whose narrative seemed quite as fully rounded as it could and should have been.

And so, no doubt presumptuously, nearly four years ago I embarked on the writing of this book. From the start my objective was to weave together all of the story’s most compelling elements—the strange way in which it began more than a month after the assassination that supposedly was its cause; the mysterious way in which the successes and failures of both sides balanced so perfectly as to produce years of bloody deadlock; the leading personalities; the astonishing extent to which the leadership of every belligerent nation was divided against itself; the appalling blunders; the incredible (and now largely forgotten) carnage—while at the same time filling in as much as possible of the historical background. And I use the word

weave

advisedly. An early decision was to intertwine the stories of the war’s major fronts rather than dealing with them separately in the usual way, and to mix foreground, background, and sidelights in such a way as to make their interconnections plain. I continue to think that such an approach is essential to showing how the many elements that made up the Great War affected one another and deepened the disaster.

It has long seemed to me that practically all popular histories of the Great War assume too much, expect too much of the reader, and therefore leave too much unexplained. In dealing with Hohenzollern Germany, for example, they commonly presume that today’s reading public knows more than a little about who the Hohenzollerns were, where they came from, and why they mattered. Authors are right, of course, in making mention of the decadence of the Ottoman Empire, the frailty of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the backwardness of the Russian Empire—of all the elements that gave rise to the war and that the war destroyed. The recurrent mistake, it seems to me, has been to

only

make mention of such things, thereby diluting the story. I believe that this volume, whether or not it has any other distinction, is unique in the extent to which it attempts to restore parts of the story that have almost always been missing. I hope that it captures at least some of the multidimensional richness of one of the most epic tragedies in the history of the world.

My final objective, and not the least of my objectives, has been to offer this story in the most

readable

form possible and thereby to do justice to its inherent drama. Candidly, this has never seemed a singularly daunting challenge. Mark Twain said it isn’t hard to be funny: one need only tell the truth. Something similar can be said about my subject: to make a great drama of the Great War, one need only be clear and careful and thorough in telling it as it was.

The war is unique in the number of questions about it that remain unsettled. Who caused it—if it can be said that anyone did? Should Germany have won it in 1914—and need Germany have lost it in 1918? Could it have ended earlier if only a few things had gone just a little differently at Gallipoli, or on the Marne, or at Ypres? Was Douglas Haig—or Erich Ludendorff, or Conrad von Hötzendorf—a great commander, or a disastrously bad one, or something in between? Could the conflict have been brought to a negotiated conclusion before it did so much damage to so much of the world? After ninety years, scholars remain divided on such questions. It seems likely that they always will. I do not claim to have the answers—am not sure that answers are possible, which is part of what makes the questions so interesting. I hope I have provided enough information to allow readers to understand why the questions persist, and perhaps in some cases to arrive at conclusions of their own.

It is testimony to the power of the story that in all these years of learning about it and developing my own account of it, I have not had one boring day. If I have succeeded in making the reader understand and perhaps even share my fascination, I will regard my labors as rewarded fully. Among the many people to whom I am grateful as this project comes to completion, I must mention my agent, Judith Riven, and my editor, John Flicker, both of whom have been indispensable and endlessly supportive. I am grateful both to and for my children, Eric, Ellen, and Sarah, and I will never forget how Paul Wagman, that best of friends, saved the whole project from a very early death.

Finally, I must try to express my admiration for and gratitude to those scholars and researchers—among whom I cannot claim to be numbered—who for nearly a century have been devoting their lives to unearthing the buried secrets of the Great War. Without their labors and achievements, works like this one would be impossible.

G. J. Meyer

New York City

January 2006

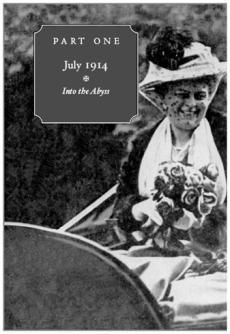

Franz Ferdinand and Sophie minutes before their assassination.

Chapter 1

June 28:

The Black Hand Descends

“It’s nothing. It’s nothing.”

—A

RCHDUKE

F

RANZ

F

ERDINAND

T

hirty-four long, sweet summer days separated the morning of June 28, when the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire was shot to death, from the evening of August 1, when Russia’s foreign minister and Germany’s ambassador to Russia fell weeping into each other’s arms and what is rightly called the Great War began.

On the morning when the drama opened, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was making an official visit to the city of Sarajevo in the province of Bosnia, at the southernmost tip of the Austro-Hungarian domains. He was a big, beefy man, a career soldier whose intelligence and strong will usually lay concealed behind blunt, impassive features and eyes that, at least in his photographs, often seemed cold and strangely empty. He was also the eldest nephew of the Hapsburg emperor Franz Joseph and therefore—the emperor’s only son having committed suicide—heir to the imperial crown. He had come to Bosnia in his capacity as inspector general of the Austro-Hungarian armies, to observe the summer military exercises, and he had brought his wife, Sophie, with him. The two would be observing their fourteenth wedding anniversary later in the week, and Franz Ferdinand was using this visit to put Sophie at the center of things, to give her a little of the recognition she was usually denied.

Back in the Hapsburg capital of Vienna, Sophie was, for the wife of a prospective emperor, improbably close to being a nonperson. At the turn of the century the emperor had forbidden Franz Ferdinand to marry her. She was not of royal lineage, was in fact a mere countess, the daughter of a noble but impoverished Czech family. As a young woman, she had been reduced by financial need to accepting employment as lady-in-waiting to an Austrian archduchess who entertained hopes of marrying her own daughter to Franz Ferdinand. All these things made Sophie, according to the rigid protocols of the Hapsburg court, unworthy to be an emperor’s consort or a progenitor of future rulers. The accidental discovery that she and Franz Ferdinand were conducting a secret if chaste romance—that he had been regularly visiting the archduchess’s palace not to court her daughter but to see a lowly and thirtyish member of the household staff—sparked outrage, and Sophie had to leave her post. But Franz Ferdinand continued to pursue her. In his youth he had had a long struggle with tuberculosis, and perhaps his survival had left him determined to live his private life on his own terms. Uninterested in any of the young women who possessed the credentials to become his bride, he had remained single into his late thirties. The last two years of his bachelorhood turned into a battle of wills with his uncle the emperor over the subject of Sophie Chotek.