A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (23 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

Leman, ordered by King Albert to hold his position at all costs (a term meaning death before surrender or retreat), learned of the appearance of German cavalry to his north and concluded that he would soon be surrounded. To keep his mobile force from capture, he sent it off to join the main Belgian army. This removed almost a quarter of Belgium’s total fighting forces from danger of encirclement and capture, but at a price: it ended any possibility that Leman would have enough troops to keep the Germans at a distance from which their guns would be unable to do their worst.

There now arrived on the scene, and on the world stage, an obscure German officer who quickly established himself as the hero of the siege and with startling speed would become one of the most important men in the German army. This was Erich Ludendorff. (Note the absence of a

von

in the name—he was not a member of Prussia’s Junker aristocracy.) Recently promoted to major general, a tall, portly, double-chinned forty-nine-year-old, Ludendorff was on temporary assignment as liaison between the Liège assault force and the German Second Army, which was still assembling on the German side of the border. There had been good reason for giving Ludendorff this assignment: a few years earlier, as a key member of Moltke’s staff, he had developed the plans for the reduction of the Liège fortifications. (With typical thoroughness, he had once spent a vacation in Belgium in order to examine the defenses at first hand.) In the German army, unlike the French, it was customary to send staff officers into the field, into combat, where they could observe their plans in action, assist in making adjustments when reality began to intrude, and learn from the experience. But Ludendorff was constitutionally incapable of remaining a mere observer or adviser. It was he who had sent the cavalry that, by showing itself north of Liège, had caused Leman to send most of his troops away. Then, coming upon a brigade whose commander had been killed in one of the early attacks, he put himself in charge. Bringing howitzers forward and directing their fire on the Belgian defenses, he led an assault that gave him possession of an expanse of high ground from which the city and its central citadel were clearly visible.

When he could see no sign of activity around the citadel (Leman had moved to one of the outlying forts), Ludendorff drove to it. He shouted a demand for surrender while pounding on the gate with the pommel of his sword. Astoundingly, he was obeyed in spite of being greatly outnumbered. Thus the centerpiece of the Liège defenses fell into German hands almost without effort. Though the circle of forts was still intact, all were now isolated and without any support except what they could give one another. Ludendorff then hurried back into Germany to see to it that more and bigger guns were brought forward without delay.

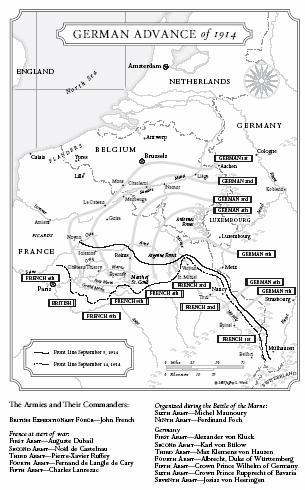

Moltke’s seven western armies, meanwhile, were forming up on a north-south line just inside the German border south of Holland. Picture a clock with Paris at its center. The line of armies was in the upper-right portion of the clock’s face, extending, roughly, from one to three o’clock. The biggest and northernmost of these armies, positioned to the north and east of Liège, was commanded by General Alexander von Kluck, tough, aggressive, irascible, and sixty-eight years old, a hardened infantryman who had begun life as a commoner and had been elevated to the nobility in reward for decades of distinguished service. Remarkably for a high-ranking German officer, Kluck had never had a tour of duty on the high command’s headquarters staff. His First Army, almost a third of a million men strong, was assigned to be the outer edge of the right wing. It would have the longest distance to travel as it moved westward across Belgium and then looped toward the southwest. If things went perfectly it would, on its way to Paris, move around and past the westernmost end of the French defensive line. It would then continue southward, circle all the way around Paris, and move back to the east. Finally it would hit the French line from the rear, pushing it into other German armies positioned at two and three o’clock and crushing it in a great vise.

The Germans did students of the war a lasting favor by arranging their armies in numerical order. Next to Kluck, immediately to his south during the mobilization (later to his east, as the Schlieffen wheel made its great turn), was the Second Army under General Karl von Bülow, a member of the high Prussian aristocracy who also was in his late sixties. Then came the Third Army, the Fourth, and so on down to the Seventh, which was almost as far south as Paris and had the Swiss border on its left. The first three of these armies made up the right wing, and though that wing no longer included as big a part of the German army as Schlieffen had intended, it was still an awesome force of seven hundred and fifty thousand troops. This was war on a truly new scale; the army with which Wellington defeated Napoleon at Waterloo had totaled sixty thousand men.

The First, Second, and Third Armies would be side by side as they drove forward. Their left would be protected by the rest of the German line. Though their right would be exposed, this would be no problem if Kluck could get around the equally exposed French left. His primary assignment, until he had circled Paris, was not to engage the enemy but to

keep moving.

If circumstances developed in such a way as to permit him to strike at the flank of the French left as he advanced, perhaps crippling it, so much the better. That would be secondary, however. The goal was Paris.

King Albert of Belgium

The two armies on the German left, the Sixth and the Seventh, were not intended to be an attack force. Their role was to absorb an expected advance by the French into Alsace and Lorraine, stopping the invaders from breaking through while keeping them too fully engaged to spare troops for the defense of Paris. Between the three armies of the right wing and the two on the left were the Fourth and Fifth Armies, the latter commanded by Imperial Crown Prince Wilhelm, the kaiser’s eldest son. They were to provide a connecting link between the defensive force in the south and the right wing, keeping the line continuous and free of gaps. They would be the hub of the wheel on which the right wing was moving, and they would not have to move either far or fast. They would be an anchor, a pivot point, for the entire campaign. Ultimately they were to become the killing machine into which Kluck was to drive the French after his swing around Paris.

French General Joffre, for his part, had his million-plus frontline troops organized into five armies. They too were forming up in a line and were in numerical order, with the First on the right just above Switzerland. The French Second Army was immediately to its north, the Third above it, and so on northward and westward in a great arc that ended approximately midway between Paris and the starting point of Kluck’s army. Joffre’s First, Second, and Third Armies, as they took up their positions, faced eastward toward Alsace and Lorraine with their backs to the chain of superfortresses (Verdun, Toul, Épinal, and Belfort) that France had constructed between Switzerland and Belgium. The Fourth and Fifth, being to the north and west of these forts, had no such strongpoints to fall back on. The position of the Fifth, commanded by Joffre’s friend and protégé Charles Lanrezac, was problematic. It was the end of the French line in exactly the same way that Kluck’s army was the end of the German, with no significant French forces to its north or west. Its left flank ended, as tacticians say, “up in the air”—out on a limb. This position carried within it the danger that the Germans might get around Lanrezac’s left, exposing him to attack in the flank or from the rear. In the opening days of the war, however, this danger seemed so hypothetical to Joffre as to be unworthy of concern.

Neither Lanrezac nor Joffre had any real way of knowing what the Germans were going to do. Aerial reconnaissance, like military aviation generally, was barely in its infancy in the summer of 1914. Until mobilization was completed, it would not be possible to make much use of the cavalry that was supposed to function as the eyes of the army. The commanders on both sides could do little more than make educated guesses, using whatever information came in from spies or could be gleaned from the questioning of captured soldiers. The sheer size of their armies and of the theater of operations, and the unavoidable remoteness from the front lines of headquarters responsible for the movements of hundreds of thousands of men, compounded the intelligence problem.

The individual armies, too, would be half-blind as they went into action. And they would be far more vulnerable than their size would suggest. A mass of infantry on the move is like nothing else in the world, but it may usefully be thought of as an immensely long and cumbersome caterpillar with the head of a nearsighted tiger. (The monstrousness of the image is not inappropriate.) It is structured to make its head as lethal as possible, ready at all times to come to grips with whatever enemy comes into its path. A big part of an army commander’s job is to make certain that it is in fact the head that meets the enemy, so that the tiger’s teeth—men armed with guns and blades and whatever other implements of destruction are available to them—can either attack the enemy or fend off the enemy’s attack as circumstances require.

An advancing army’s worst vulnerability lies in the long caterpillar body behind the head. (

Long

is an inadequate word in the context of 1914: a single corps of two divisions included thirty thousand or more men at full strength and stretched over fifteen miles of road when on the march.) Great battles can be won when a tiger’s head eludes or even accidentally misses the head of its enemy and makes contact with its body instead. When this happens the enemy is “taken in the flank,” and if an attacking head has sufficient weight it can quickly tear the enemy’s body apart, finally reducing even the head to an isolated, enfeebled remnant. Much the same can happen when an army on the move is taken in the rear, or surrounded and cut off from its lines of supply. Hence the importance that Moltke and Joffre attached to arranging their armies in an unbroken line, so that each could protect the flanks of its neighbors. Hence too the dangers inherent in the fact that both generals would begin the war with one end of their lines unprotected.

Joffre, like Moltke, was intent upon taking the offensive. His master plan, approved in 1913, reflected the French government’s refusal to permit any move into neutral territory. It assumed that the Germans too would stay out of Belgium and Luxembourg, and so it assumed further that the first great clash of the war would take place on the French-German border, somewhere between Verdun to the north and the fortress of Belfort to the south. Joffre’s five armies were more than sufficient to maintain a solid line while attacking from one end of that border to the other, and so he saw no reason to be concerned about Lanrezac’s left, which would be anchored on Luxembourg.

Joffre’s advantage was that he was not irrevocably committed to attacking at any specific place or time or even to attacking at all. Unlike Moltke he had options—he could change his plans and the disposition of his armies according to how the situation developed. This ability quickly proved important: when the Germans moved into Luxembourg and then on to Liège, Joffre was able to order the Fourth and Fifth Armies to shift around and face northward. He now expected the Germans to come from the northeast, through Belgium’s Ardennes Forest toward the French city of Sedan. His left wing would move north to meet them.

Lanrezac was not so sure. As word reached him of the intensifying assault on Liège, he could think of no reason for it unless the Germans needed to clear a path to the west. As early as July 31—before war was declared—he had sent a message to Joffre expressing concern about what would happen if the Germans advanced westward while his army stayed south of the Belgian border or moved east to join in the French offensive. “In such a case,” he warned, “the Fifth Army…could do nothing to prevent a possible encircling movement against our left wing.” Joffre did not respond; he was certain that no such thing would happen. A week later, with the Germans continuing to concentrate troops opposite Liège, Lanrezac sent another appeal. “This time there can be no doubt,” he said. “They are planning a wide encircling movement through Belgium. I ask permission to change the direction of the Fifth Army toward the north.” He had it exactly right, but Joffre remained unpersuaded, confident that whatever was happening around Liège must be a German feint intended to lure his forces out of position. His attention was focused on launching an attack by his right wing into Alsace and Lorraine—the capture of France’s lost provinces would be a tremendous symbolic triumph. As a precaution, though, he did send cavalry on a scouting expedition into Belgium. When this foray found no evidence of German activity—inevitably, the Germans not yet having moved beyond Liège—Joffre felt free to proceed with his own plans. His First Army began crossing into Alsace as early as August 7, the day Ludendorff captured the Liège citadel, and it made good progress. Another week passed, and the direction of the German right wing became undeniable, before Joffre at last responded to Lanrezac’s warnings, telling him almost laconically that “I see no objection (to the contrary) to your considering the movement that you propose.” Even then he added, with thinly veiled annoyance, that “the threat is as yet only a long-term possibility and we are not absolutely certain that it actually exists.” Lanrezac started northward, not knowing that it was already too late for him to escape being outflanked in exactly the way he had feared from the start.