A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (63 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

Previous pages

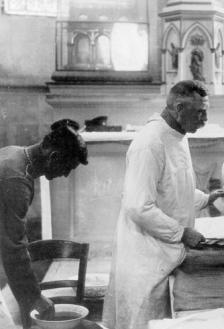

: Surgery in a French church

Myers’s analysis of the relationship between trench warfare and breakdown—which came to be called

hysteria

when the victims behaved manically, neurasthenia when they sank into depression—was confirmed as the war continued. Observers noticed that breakdowns had been least frequent in the opening months of the war, before the Western Front became rigid (and later that their frequency declined when the deadlock was broken and the armies again began to move). Further confirmation came in the fact that one in six victims was an officer, although the BEF had only one officer for every thirty men. Junior officers on the front lines not only bore heavier responsibilities than the men they commanded but were more often exposed to enemy fire.

By trial and error, it was discovered that soldiers who broke down were most likely to recover when treated almost immediately, at casualty clearing stations behind the lines, rather than being sent to hospitals. Various treatments were tried—hypnosis, electric shock, simple and often bullying forms of talk therapy—and several proved to be at least somewhat effective. Treatment was often indistinguishable from punishment. Men unable to talk were given electric shocks until they screamed in pain, at which point they were declared to have recovered. Always the objective was not to “cure” the victim, to identify and deal with the underlying causes of his symptoms, but to get him back into action. The British created two categories of cases: men who had broken when actually under fire, and those who had not been under fire. Only those in the first category were entitled to wear on their sleeves the stripe awarded to men wounded in action, and only they, if they did not recover, were entitled to disability compensation. It remained inadmissible for physicians to suggest that a loss of the will to fight could ever be justified. The few who dared to suggest that it might be rational for a man to disobey an order that could not possibly lead to anything except sudden death—an order to climb out of a hole into blanketing gunfire, for example—were likely to be dismissed. Any nonmedical officer who seriously challenged such orders was dismissed or worse.

The problem remained immense. This is an area in which data are scarce—little is known about the incidence or treatment of shell shock among the Austrians and Russians, though the continued fluidity of the Eastern Front may have limited the problem there. But by the end of the war, two hundred thousand shell shock cases entered the medical records in Germany, eighty thousand in Britain. Sixteen thousand cases were reported by the British just in the second half of 1916, and this total included only those men in the first category, the ones whose problems were judged to be less dishonorable. Fifteen percent of all the British soldiers who received disability pensions—one hundred and twenty thousand men in all—would do so for psychiatric reasons. In 1922, four years after the war’s end, some six thousand British veterans would remain in insane asylums.

Chapter 21

Verdun Metastasizes

“Verdun was the mill on the Meuse that ground to powder the hearts as well as the bodies of our soldiers.”

—C

ROWN

P

RINCE

W

ILHELM

O

n March 6, after a week when the artillery on both sides continued to pound away but infantry operations were limited to attacks and counterattacks of little consequence, the Germans attempted to restart their stalled offensive. In keeping with the conditions that the crown prince had set in agreeing to continue, they did so with many more troops this time (Falkenhayn had released a corps of reserves) and on a much broader front. They again attacked in the craggy wooded hills east of the Meuse, but now they also made a complementary move on the west or left bank. There the main objective was Le Mort Homme, the ridge from which French gunners had been sending fire across the river. The battle remained above all an artillery contest. As on February 21, the Germans began by trying to use their firepower to obliterate the defenders. Once again men died by the hundreds without seeing or being seen by the men who killed them.

The balance had shifted, however. The French had hurried two hundred thousand troops up the Voie Sacrée from Bar-le-Duc, and the long-range guns that they had positioned all through the region were wrecking the Germans’ howitzers. Pétain, anticipating a German advance on the west bank, had positioned four divisions of infantry there—something on the order of sixty thousand troops—with a fifth in reserve. Though not fully recovered from pneumonia, he was back on his feet and directing everything.

Conceivably, if he had been free to make his own decisions, Pétain might have elected to withdraw from Verdun. He understood that he would have sacrificed nothing of strategic importance in doing so, and he would have left the Germans in a difficult position from which to proceed. But he knew too that President Poincaré, for reasons of national morale, had demanded that the city be held, and that if he proposed anything different he would likely be dismissed. Fortunately for him, the Falkenhayn plan had by this point lost all coherence. The dynamics of the situation were drawing the Germans into a nearly obsessive willingness to attack and attack again regardless of cost, and to attack not only with guns but with troops. Blindness, loss of perspective, had become a more serious affliction on the German side than on the French.

On the ravaged ground of the east bank, after again throwing masses of infantry against reinforced French defenses and murderous artillery fire, the Germans found themselves reeling under the magnitude of their losses and unable to advance. On the new battleground west of the river too, the center of the attack was quickly stopped. Only on the left flank of the west bank offensive, the flank directly adjacent to the Meuse, was the story different. There the attackers made rapid and substantial progress, managing to blast the French out of village after village, capturing the first and then the second lines of defense along four miles of front, taking thousands of prisoners. The situation became so desperate, the danger of a general collapse so great, that the sector’s French commander issued a warning to his troops. If they tried to withdraw, he would order his own artillery and machine guns to fire on them.

The Battle of Verdun began to settle down into stalemate. On March 7 the Germans’ drive on the west bank brought them up against a woodland called the Bois des Corbeaux, one of several points protecting the approaches to Le Mort Homme. Artillery wiped out many of the defenders, put the survivors to flight, and allowed the Germans to take possession of the woods. Early the next morning the French returned in a wildly courageous counterattack that should have been a disaster but through sheer audacity panicked the Germans and sent them running. But the next day, when a blast of artillery blew off both legs of the dashing colonel who had led the counterattack carrying only a walking stick, the Germans yet again captured the Bois. This time they held it. But the victory was little more than pyrrhic. It left the Germans exhausted and pinned down. Not only Le Mort Homme but the high points nearest it remained in French hands, bristling with artillery and machine guns, guarded by entrenched riflemen. Further movement was out of the question.

The crown prince’s attack on two sides of the river had miscarried as badly as Falkenhayn’s on one. If the French were being bled white, so were the Germans. The two sides were draining each other in a fight so huge and costly, so rich in drama, that it had captured the imagination of the world. Verdun had been elevated to such colossal symbolic importance that France needed only to hold on in order to claim a momentous victory. Falkenhayn, originally indifferent to whether Verdun fell or not, now desperately needed to take it. The trap that he had wanted to construct for the French now held him firmly in its grip.

As a direct result of Verdun, the war in the east flared back into life. Late in 1915, when the Entente’s senior commanders met to make plans, the Russians had complained about what they saw as their allies’ failure to help when the Germans were hammering them out of Poland. General Mikhail Alexeyev, sent to Chantilly as the tsar’s new chief of staff, demanded an agreement that whenever one front was threatened, an offensive would be launched on the other to relieve the pressure. The Battle of Verdun was only days old when the French reminded Petrograd of this commitment. The Russians responded with yet another expression of their almost touching readiness to try to come to the rescue whenever asked—an eagerness that contrasted sharply with the cynicism and contempt that so often tainted relations between the British and the French. It is difficult to imagine Joffre or Haig responding as the Russians did if the situation had been reversed.

Only the tsar was really eager. When the Russian general staff gathered at his headquarters on the third day of fighting at Verdun, the army group commanders argued that they were not ready for an offensive and attacking now could only spoil their chances of doing so successfully later. They pointed out that the spring thaw was approaching and that the resulting floods would usher in the annual “roadless period,” during which movement of men and guns became all but impossible. Tsar Nicholas decided otherwise. He ordered not only that an attack be launched but that it take place in advance of the thaw. The only remaining question was where to hit the Germans.

The Russians appeared to have good options from which to choose. The loss of Poland had enormously shortened their lines, increasing the number of troops available for each mile of front. In the north, in the sector commanded by Hindenburg and Ludendorff on the German side, the Russians had three hundred thousand troops to the Germans’ one hundred and eighty thousand. In the center the Russian advantage was even greater: seven hundred thousand men facing three hundred and sixty thousand Germans. In the south, where the front slanted eastward toward the Balkans, things were more evenly balanced, with half a million men on each side. Here, however, the enemy troops were mainly Austro-Hungarian rather than German and therefore considerably less intimidating. That the Russian troops were largely half-trained recruits and deplorably ill equipped (tens of thousands remained without rifles) seems to have caused little more concern than the questionable quality of their leadership. Though the whole vast Russian army was a sorry mess by the standards of the Germans, French, and British, War Minister Alexei Polivanov was improving training and supply. Recent events gave cause for encouragement. Grand Duke Nicholas had launched an offensive in the Caucasus in January and within a week had won a major victory over the Turks at Koprukov. On February 16 his forces had captured Erzerum, the Ottoman Empire’s most important northern stronghold. Obviously Russian armies were capable of winning.

It was decided that the new offensive should take place in the northwest, at Lake Naroch near the Lithuanian capital of Vilna, and should include the northern and central army groups. Together they could provide ten corps, more than twenty divisions, enough to outnumber the Germans by what promised to be a decisive margin. They were commanded by two of the most senior Russian generals, Alexei Evert and Alexei Kuropatkin.