A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (66 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

The Germans’ nightmare deepened on May 8, before anyone had an opportunity to celebrate the conquest of Côte 304, when Fort Douaumont suddenly blew up. No one lived to explain what had happened, but there had been complaints that ammunition was not being handled properly as it was moved into and out of the fort. The prevailing theory, based on evidence collected after the disaster, is that it began when a group of Bavarian soldiers sheltering inside Douaumont opened a hand grenade to get a few thimblefuls of explosive for use in heating coffee. The resulting fire is believed to have ignited a cache of grenades, which in turn set off some flamethrower fuel tanks, which in turn started a chain reaction among stacked artillery shells. Whatever the cause, some six hundred and fifty German soldiers were killed. The few survivors, emerging from the depths of the fort with faces blackened by the blast, were immediately shot by German troops who had no idea what had happened inside and assumed that the fort had been overrun by French colonial units from Africa.

Spirits were not high, understandably, when the staff of the German Fifth Army met at the crown prince’s headquarters on May 13 to discuss an east bank offensive that had been repeatedly delayed because of weather, the disruptive though otherwise unsuccessful attacks being launched repeatedly by Nivelle and Mangin, and ongoing artillery fire from Le Mort Homme. The crown prince, having given up on Verdun, was urging both Falkenhayn and the kaiser to call off not only the new offensive but the entire campaign. In doing so he was putting himself at odds with Knobelsdorf, who before the war had been his tutor in tactics, since August 1914 had been his chief of staff and mentor, and remained convinced that Verdun could be taken. He and Falkenhayn were encouraged by the false belief (mirrored by equally wrong French estimates of German casualties) that their enemies had by now lost well over two hundred thousand men.

A surprising unanimity emerged. Even Knobelsdorf conceded that enough was enough. He promised, in fact, to visit Falkenhayn that same day and try to persuade him to bring Verdun to an end. What happened next has never been explained. When he reached Falkenhayn’s headquarters, Knobelsdorf did the opposite of what he had promised. He told Falkenhayn that the French guns at Le Mort Homme would soon be silenced and that the east bank offensive could then be safely resumed. Getting agreement from Falkenhayn, who by now had staked his place in history on Verdun, is not likely to have been difficult. No doubt Falkenhayn was mindful of the fact that the leading pessimists—the crown prince, Gallwitz, and others—all had opposed his elevation to commander in chief after the fall of Moltke. The crown prince, when he learned of Knobelsdorf’s betrayal, could do nothing. Though heir to the imperial throne, he had been treated with disdain by the kaiser all his life. Even now, after a year and a half as an increasingly competent and serious-minded army commander, during which time he had gradually acquired the confidence to stand up to the iron-willed Knobelsdorf, he was kept at a distance from his father.

And so the carnage would continue. It would be accelerated, in fact, as Knobelsdorf hurried with Falkenhayn’s encouragement to complete the capture of Verdun before Joffre and the British were ready with the offensive that they were obviously preparing along the Somme. The crown prince could only complain that “if Main Headquarters order it, I must not disobey, but I will not do it on my own responsibility.”

The hopes of the optimists were about to be upended by the man who supposedly was their one great military ally, the Austrian Conrad. In the course of his career Conrad had been obliged to watch the new Kingdom of Italy encroach on the Austro-Hungarian territories to its north, and he had developed a nearly pathological hatred and contempt for the Italians. (“Dago dogs,” he called them.) Since late 1915 he had been badgering Falkenhayn for help in mounting an offensive southward out of the Alps, a campaign that would destroy Italy’s ability to wage war and restore Vienna to possession of the north Italian plain. Falkenhayn, his armies outnumbered on every front and his attention focused on Verdun, had brushed these appeals aside. He pointed out that while conquests in Italy might bring pleasure to Vienna, they could contribute little to the winning of the war. He had done so with unnecessary brusqueness. An outwardly cold figure, Falkenhayn had no close friends even among his fellow Junkers, and he disliked and distrusted Conrad. He demolished whatever possibility remained of a constructive working relationship with Conrad by keeping him in the dark. The Verdun offensive had come as more of a surprise to the Austrians than to the French. And though Falkenhayn’s secretiveness had not been directed exclusively at Conrad (for valid reasons he had drawn such a curtain of security over his preparations that not even the commanders of the German armies west and south of Verdun knew exactly what was coming), the Austrian was deeply offended. He decided not only to proceed with an Italian campaign but to tell the Germans nothing of what he was doing.

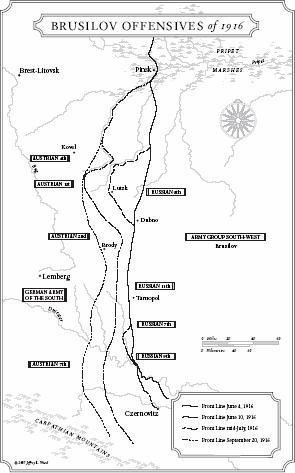

His plan was to attack not at the Isonzo, already the scene of four battles and still the place where the Italians were concentrating most of their forces, but farther west, in the mountainous Trentino region northeast of Lake Garda. He began by sending more than a dozen of his best remaining divisions to an assembly point just north of the passes leading into Italy. From there they would be able to descend upon the farmlands and cities of Lombardy, lands and cities that in Conrad’s view rightfully belonged to Vienna. Once in open country, the Austrians could wheel around and take the Italians on the Isonzo in the rear. Not for the first time and not for the last, Conrad smelled triumph. Six of the divisions committed to the Trentino were taken from Galicia, where he saw no possibility of trouble. The Russians had been thoroughly thrashed in Galicia in late 1915 (though mainly by German troops that Falkenhayn had since sent to Verdun), and their numerical advantage was smaller there than at any other point on the Eastern Front. If Conrad was even aware of the appointment of Alexei Brusilov as commander of Russia’s southwestern front, he could not have regarded it as significant. He secured pro forma approval of his plan from the Hapsburg archduke who was his official commander in chief and assumed personal command of operations in Italy.

Conrad consistently asked his troops to do things that were beyond their capacity. If he was the strategic genius that some historians have called him, he was also less than a realist. He would venture forth not just to meet and fight his enemies but to crush them, to destroy them even when he was terribly outnumbered. And there was a pattern to his campaigns. They would begin thrillingly, with spectacular gains, and they never failed to end in disaster except when the Germans came to his rescue. Their cumulative result, by early 1916, was the loss of so many troops (more than two million casualties in 1915 alone, including seven hundred and seventy thousand men taken prisoner) that the Austro-Hungarian military was at the end of its ability to mount independent operations. Perhaps this accounts for Conrad’s eagerness to invade Italy. Perhaps even he had lost confidence in his ability to accomplish anything on the more challenging Russian front.

In taking charge of the Trentino campaign, Conrad did not move his headquarters to or even near the places where the invasion force was being assembled. He did not even pay them a visit. He remained in Silesia, six hundred miles to the north, where he had happily settled with a new wife and all the comforts of prewar aristocratic life. He perfected his isolation by keeping all communications on a one-way basis, and by sending out detailed instructions as to exactly what the Austrian divisions in the Trentino were to do, and when and where, while ignoring questions and suggestions. He drew marks on maps showing which objectives each division was supposed to reach each day, and as far as he was concerned that was that. If following his instructions required the troops to climb through deep snow over a mountain crest when they could have reached the same objective by moving downhill through a valley, that too was that. No discussion was wanted or tolerated. When the chief of staff of the army group being formed in the Trentino requested permission to travel to Silesia and confer with Conrad, he was refused.

Conrad had wanted his offensive to begin almost immediately, in April, but on this point he had to bend to reality. Neither his troops nor their supply trains could get into position that quickly at that time of year, though hundreds froze to death or were buried in avalanches in the attempt. When the Austrians finally attacked on May 15, they were one hundred and fifty-seven thousand strong. The one hundred and seventeen thousand Italians standing in their path were rather easily pushed back. True to the Conrad pattern, the Austrians made progress for three weeks, sweeping southward on a broad front. By the end of May they had captured four thousand prisoners and 380 guns. The tsar, accustomed by now to urgent appeals from Joffre, found himself being begged for assistance by the King of Italy as well.

There were good reasons for Nicholas to pay heed, and they went beyond Verdun and the Austrian invasion of Italy. Everything seemed to be working in favor of the Central Powers. North of Paris, a German attack intended mainly to disrupt French and British preparations for their summer offensive had shocked Joffre by driving the British out of positions from which they had been preparing to take Vimy Ridge, an immense strongpoint dominating the plain of Artois to the west. The French had sacrificed mightily in establishing those positions, and had regarded them as secure when, in March, they handed them over to the British. Haig, though humiliated by the loss, was unable to organize a counterattack because so many of his resources were now being concentrated at the Somme.

At Verdun on May 22, “Butcher” Mangin, dreaming his dreams of glory and confident of success, opened an attack aimed at retaking Fort Douaumont. The bitterness of the struggle was becoming unnatural, almost psychotic. “Even the wounded refuse to abandon the struggle,” a French staff officer would recall. “As though possessed by devils, they fight on until they fall senseless from loss of blood. A surgeon in a front-line post told me that, in a redoubt at the south part of the fort, of 200 French dead, fully half had more than two wounds. Those he was able to treat seemed utterly insane. They kept shouting war cries and their eyes blazed, and, strangest of all, they appeared indifferent to pain. At one moment anesthetics ran out owing to the impossibility of bringing forward fresh supplies through the bombardment. Arms, even legs, were amputated without a groan, and even afterward the men seemed not to have felt the shock. They asked for a cigarette or inquired how the battle was going.”

In the five days preceding the start of his attack, Mangin’s three hundred heavy guns had fired a thousand tons of explosives onto the quarter of a square mile centered on the fort, and the assault that followed broke into the fort’s inner chambers. The Germans regrouped, however, and after days of hellish close-quarters underground combat drove the attackers out. The failure had been so complete and the costs so high—more than fifty-five hundred troops and 130 officers killed or wounded out of twelve thousand French attackers, another thousand taken prisoner—that Mangin was relieved of command. “You did your duty and I cannot blame you,” Pétain told him resignedly. “You would not be the man you are if you had not acted in the way you did.” Meanwhile, in almost equally intense fighting nearby, the Germans were forcing their way closer to Le Mort Homme.

By this time General Mikhail Alexeyev, still in place as the tsar’s chief of staff in spite of having been the fallen Polivanov’s partner in reform (he had survived, probably, by virtue of being at army headquarters and therefore remote from the intrigues of Petrograd), was asking his sector commanders when they could attack. Evert said predictably that he was able to do nothing. Brusilov surprised even Alexeyev by answering that his preparations were essentially complete, his four armies ready to go. It was decided that Brusilov would attack at the beginning of June. Evert, directly to his north, was coaxed into agreeing that he would send his immensely larger forces into action on June 13. He was reluctant in spite of having a million men under his command and two-thirds of Russia’s heavy artillery.

On May 26 Joffre met with Haig, at the insistence of Pétain, and asked him to move up the date of the Somme offensive from mid-August. Haig disliked the idea, but when Joffre told him that if he waited another two and a half months “the French army could cease to exist,” he yielded.

On May 31, for the first and last time in the war, the dreadnoughts of the British Grand Fleet and Germany’s High Seas Fleet met in battle. The German commander, having concocted a plan to lure Britain’s battle cruiser force southward away from the protection of dreadnoughts, had steamed into the North Sea the previous day with a mighty array of ships: sixteen dreadnoughts, six older battleships, five battle cruisers, eleven light cruisers, and sixty-one destroyers. Unknown to him, the British, having intercepted and decoded his radio messages, were coming at him with a hundred and fifty ships that outnumbered him in every category.

They met near Jutland, a peninsula on the Danish coast, and what followed was the greatest sea battle in history until the Second World War. It was a complex and confused affair, unfolding in five distinct stages as the fleets separated and converged and changed directions again and again, and it was marked by serious mistakes and much ingenuity on both sides.