A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (69 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

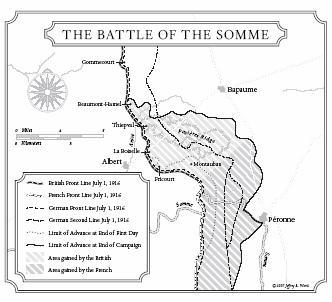

First conceived in the closing days of 1915 as one part of a great combination of attacks by Britain and France and Russia and Italy on every one of Europe’s many fronts, the battle was long in the making. The whole first half of 1916 was devoted to building up great masses of armaments, to bringing forward the green new armies that Kitchener had recruited in 1914, to literally laying the groundwork (in the form of new roads and railways and lines of communication) for a success so complete that the enemy would be crushed and stalemate would be transformed into sudden, final, total victory.

As originally planned, the offensive was to be a French show primarily, with forty of Joffre’s divisions providing most of its weight and the British in a secondary role. But the unexpected upheavals of the first half of 1916—Verdun first, then Lake Naroch, and finally Conrad’s offensive in Italy and Brusilov’s in Galicia—disrupted everything on all sides. As Verdun went on and on, most of the French army was run through Falkenhayn’s killing machine. As unit after unit was chewed up, Joffre gradually (and resentfully) found himself unable to assemble even half the number of troops he had originally wanted for the Somme. Lake Naroch meanwhile paralyzed the will of the men commanding Russia’s central and northern fronts; Conrad’s Trentino campaign rendered Italy incapable of a summer offensive; and the Brusilov offensive (undertaken, it should be remembered, in response to French appeals for help) had a similar impact on the Russians in the south.

The British alone were untouched. Of all the Entente commanders, only Haig remained free to proceed almost as if no battles were happening anywhere. And Haig cannot be accused of failing to make use of his great gift of time. He devoted the first half of 1916 to two things: to preparing for a fresh offensive in Flanders, where he hoped to join with the Royal Navy in retaking Belgium’s Channel ports, and to getting ready (reluctantly at first) for the offensive that Joffre was determined to launch on the Somme. As the so-called “Kitchener’s armies” arrived on the continent, they were alternated between routine line duty on quiet sectors of the front and training that included mock assaults on simulated enemy trenches. By June Haig had half a million men on and behind the Somme front. New guns were arriving as well, along with mountains of the shells being bought from America and produced by Lloyd George’s ministry of munitions. Along with them came all the bewildering panoply of equipment and supplies required by a modern army readying itself for action. Seven thousand miles of telephone lines were buried to keep them from being cut by German artillery, and 120 miles of pipe were laid to get water to the assembling troops. Ten squadrons of aircraft—185 planes—were brought in to drive off the suddenly outclassed German Fokkers and serve as spotters for the gun crews as they registered on their assigned targets. Tunnelers were digging out cavities under the German lines and packing them with explosives. It was a massive undertaking, all done as efficiently as anyone could have expected, and ultimately Haig was responsible for every bit of it.

The planning of the attack was his responsibility too, and there lay the rub. Haig had eighteen divisions on the Somme by early summer, and two-thirds of them were used to form a new Fourth Army under General Sir Henry Rawlinson, who had been with the BEF from the start of the war. Rawlinson was a career infantryman—the only British army commander on the Somme not, like Haig, from the cavalry—and his ideas about how to conduct the coming offensive differed sharply from those of his chief. Haig wanted a breakthrough. He was confident that his artillery could not merely weaken but annihilate the German front line, that the infantry would be able to push through almost unopposed, and that this would clear the way for tens of thousands of cavalry to reach open country, turn northward, and throw the whole German defensive system into terminal disorder.

Rawlinson, by contrast, had drawn the same lessons as Falkenhayn from a year and a half of stalemate. He thought breakthrough impossible, and that trying to achieve it could only result in painful and unnecessary losses. He opted for a battle of attrition, one intended less to conquer territory (there being no important strategic targets anywhere near the Somme front, actually) than to kill as many Germans as possible. To this end he favored “bite and hold” tactics similar to those with which Falkenhayn had begun at Verdun. Such tactics involved settling for a limited objective with each attack, capturing just enough ground to spark a counterattack, and then using artillery to obliterate the enemy’s troops as they advanced. Rawlinson and Haig never resolved their differences; rather, they opened the battle without coming to an understanding on what they were trying to do or how it should be done.

The men of the Fourth Army were as new to war as they were eager for it after eighteen months of training. Haig was untroubled by their lack of experience. In this regard it was he who was like Falkenhayn at the start of Verdun. He had fifteen hundred pieces of artillery, one for every seventeen yards of the eighteen miles of curving front along which the BEF would be attacking. Between them the British and French had 1,655 light, 933 medium, and 393 heavy guns. The corresponding numbers on the German side were 454, 372, and eighteen. Haig’s confidence that his batteries could paralyze the German defenses before his infantry climbed out of its trenches was communicated down the chain of command. “You will be able to go over the top with a walking stick, you will not need rifles,” one officer told his troops. “When you get to Thiepval [a village that was one of the first day’s objectives] you will find the Germans all dead. Not even a rat will have survived.”

Every part of the attack was planned to the minute. Every unit was told what points it would reach in the first hour and exactly where it would be at the end of the day. And though in the end Haig did not have quite as many weeks to prepare as he wanted—the emergency at Verdun made that impossible—the tightening of the schedule still left him with time to do everything needed. It had no effect on the conduct of the campaign, or on his serene confidence that the machine gun, “a much-overrated weapon,” could be overcome by men on horseback. He was ready enough by June 24, when French Premier Briand came to implore him for help, to begin his artillery barrage.

The French had one corps of Ferdinand Foch’s Army of the North positioned on the north bank of the Somme, immediately south of Rawlinson, and five others arrayed along an eight-mile line extending southward from the river. They were even better equipped than the British with artillery, especially heavy artillery, a weapon in which France had been deficient at the start of the war. Their assignment was a holding attack intended to make it impossible for the Germans opposite to shift their reserves (of which they had virtually none) northward to stop Rawlinson’s advance.

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig

Commander of the British

Expeditionary Force

Attacked often—and continued his attacks too long.

Facing them all, bracing for the attack that was all too obviously coming, was a stripped-down German Second Army under General Fritz von Below. Below had only seven divisions along the entire front, five north of the river and two to the south. Because they were so few, all of them were up on the front line—a dangerous arrangement, but an unavoidable one in light of how badly the Germans were outnumbered. The particular thinness of the German line opposite the French was Falkenhayn’s doing: confident that Verdun had left the French incapable of attacking anywhere else, he had instructed Below to deploy his troops accordingly. But the German preparations had been superb, and Falkenhayn was responsible for that too. Under his instructions the Germans had been doing much more than merely digging trenches. The infrastructure they had put in place was a marvel of engineering, designed so that all the strongpoints protected each other and any enemy penetration could be quickly isolated. Beneath and behind the trenches, thirty feet and more deep in the chalk that underlay the rich topsoil of Picardy, the Germans had created what was almost an underground city, a long chain of chambers and passageways reinforced with concrete and steel. This human beehive was equipped with electric lighting, running water, and ventilation and was impervious to all but the most powerful artillery. Above it, slowly crumbling under Haig’s barrage but still largely ready for use when the time came, were three (and in some places more) lines of trenches that together formed a defensive zone up to five miles deep.

Haig’s plan called for five days of bombardment, but when rain began to fall on June 26 and continued into June 28 a two-day postponement had to be ordered to allow the ground to dry. The intensity of the barrage was reduced so that the supply of shells would not run too low. Still, it remained a staggering display of power. By the time the troops went over the top on July 1, more than 1.5 million shells had descended upon the German lines—a quarter of a million on the morning of the attack alone. A ton of munitions had been dropped on every square yard of German front line with the same spirit-crushing results that both sides had been experiencing at Verdun for more than four months. “Shall I live till morning?” one of Below’s soldiers wrote in his diary. “Haven’t we had enough of this frightful horror? Five days and five nights now this hell concert has lasted. One’s head is like a madman’s; the tongue sticks to the roof of the mouth. Almost nothing to eat and nothing to drink. No sleep. All contact with the outer world cut off. No sign of life from home nor can we send any news to our loved ones. What anxiety they must feel about us. How long is this going to last?”

The Tommies and poilus looked on happily, rejoicing in the thought that nothing could survive such an inferno. And indeed the Germans were hurt, and badly. Nearly seven thousand of them died under the shellfire, and many of their guns were destroyed. Even for the survivors, the underground city became a chamber of horrors in which they could only cower in the dark, unable to bury the dead bodies around them, waiting for death. But tens of thousands survived, especially opposite the British lines. Somehow they remained sane, watching through periscopes for signs of movement on the other side. Their artillery was likewise invisible. Weeks before, the German gunners had taken the range of the British and French trenches and likely lines of advance. Then they too had gone underground, their weapons concealed in woods and covered with camouflage. Their unbroken silence made it seem certain that they too had been destroyed.

The attack, when it came, could scarcely have been less of a surprise. The area through which the front snaked is open, rolling farmland. Though the landscape was studded with woods, there were none in no-man’s-land, which was clear at almost every point, open to view. Late on the afternoon of June 30 the British units chosen to lead the assault were mustered out of the villages where they had been waiting and started toward the front. As they filled the roads, they became obvious to German observers on high points behind the front. Great columns of cavalry came forward as well. It took no Napoleon to perceive the meaning of it all. As the Germans settled in for another night of agony, they did so knowing that the hour of truth was at hand.

Midsummer nights are short in the north of Europe, and in July in Picardy the sky is dimly alight by five

A.M.

This is also a region of predawn mists and low-lying fog. Haig could have kicked off his offensive in the early light; had he done so, his troops might have crossed no-man’s-land almost unseen. But the French had insisted on a later start, and Haig found it necessary to comply. At exactly 6:25

A.M.

, as on all the days preceding, the British ended their usual early-morning cease-fire and started blasting away as usual. They had established this routine as a way of lulling the Germans into thinking that July 1 was going to be just another day. But this was an unlikely conclusion for them to reach, considering what they had seen the evening before.

Ten minutes before the start of the attack, at 7:20

A.M

., the British detonated a huge mine that they had excavated under a German redoubt at Hawthorne Ridge, near the village of Beaumont-Hamel. “The ground where I stood gave a mighty convulsion,” a distant British observer reported. “It rocked and swayed…Then, for all the world like a gigantic sponge, the earth rose in the air to a height of hundreds of feet. Higher and higher it rose, and with a horrible grinding roar the earth fell back on itself, leaving in its place a mountain of smoke.” Terrifying and deadly as the explosion was, it was too limited in its effects to justify the final alert that it sent to the Germans up and down the line. And now it was the turn of the British to receive a signal—a chilling one. The supposedly extinct German artillery suddenly opened up, its fire falling with stunning accuracy on the trenches in which the British soldiers waited. Obviously the Germans were still out there. Obviously they still had guns, and obviously those guns were registered for maximum effect. Ten remaining British mines, none of them as big as the one at Hawthorne Ridge, went off at 7:28. Two minutes later whistles blew and scores of thousands of British troops hauled themselves up onto exposed ground and started toward what every one of them must have hoped was nothing more than the dirt tombs of their enemies.