A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (82 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

They were never mere murderous robots, however. During the 1905–6 revolution, their arrangement with the Romanovs threatened to break down when Cossack regiments mutinied rather than allow themselves to be used to stamp out rebellion by peasants and workers. A crisis was averted only by the dissolution of the disloyal units. When the Great War came almost a decade later, the Cossacks were once again ready for duty. They were mobilized en masse, boys and middle-aged men alike, creating severe hardships for the families left behind. They made up at least half of the Russian cavalry, and the willingness of the Russian general staff to send them and their horses against German machine guns made the war even more disastrous for them than for most Russians. By 1917, when they were called upon once again to put down popular uprisings, many of them had had enough. They stood aside and allowed the revolution to proceed.

Of all the signs that Nicholas II and his whole system were finished, this was the clearest.

Chapter 28

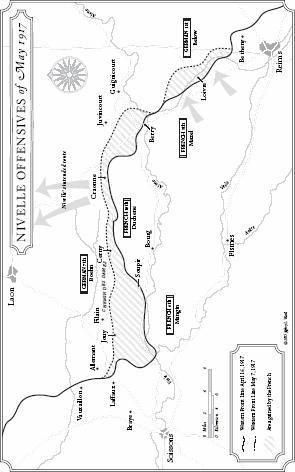

The Nivelle Offensive

“Do you know what such an action is called?

It is called cowardice.”

—G

ENERAL

A

LFRED

M

ICHELER

A

mazingly, the first three months of 1917 had passed without huge effusions of blood on any of Europe’s fronts. Men were still being killed by the hundreds, but not in great offensives. They were dying in what had become merely the routine way. They died every day in the almost absentminded exchanges of artillery and sniper fire that punctuated life in the trenches. They died every night in the dark bloody excursions into no-man’s-land that had become so common that almost no one noticed.

On April 6 France’s political and military leadership gathered in President Poincaré’s railroad car in the forest of Compiègne near Paris. The subject was the impending offensive that would, General Robert Nivelle promised, bring the war to an end. The purpose of the meeting, however, was not to complete the planning of that offensive. It was to settle the question of whether the offensive was going to happen at all. Among those opposed were General Alfred Micheler, a Somme veteran chosen by Nivelle to command the army group that would attack at the Chemin des Dames, and Paul Painlevé, the recently appointed minister of war. The latter had not abandoned his efforts, which began almost the day he took office, to persuade Nivelle to reconsider. By the start of April he was practically begging, promising Nivelle that in light of the German pullback to the Hindenburg Line no one would think less of him if he changed his mind. Painlevé lacked the authority to decide the issue, however. Only Poincaré could do that.

The arguments for not proceeding were almost overwhelming. It was certain that the United States was coming in—its declaration of war became effective, in fact, on the day of the Compiègne meeting. This meant that the French could afford to rest their worn-down armies while waiting for the Americans to arrive. The fall of Nicholas II, which promised democracy in Russia and a restoration of Russian morale, also suggested that 1917 would be a good year for France to husband her strength. What mattered even more was the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line; this move, as Painlevé and others pointed out repeatedly, had destroyed many of the premises on which Nivelle’s plan had been based from the start. The German defensive line was miles shorter and much stronger than it had been at the turn of the year. Many of the positions that Nivelle had intended to attack were now abandoned. The territory beyond those positions had been left a barren wasteland; Ludendorff, in pulling his forces back, had imitated the scorched earth policy used effectively by the Russians in retreating from Poland in 1915. Every building, every tree, every bit of railway, and every crossroads had been destroyed in the thousand square miles that the Germans gave up, and the Entente was slow to take possession of the resulting desolation. The British and French would have to attack at the two extremities of the Hindenburg Line, with a mixed command under Haig at the western end near Arras and most of the French miles to the east. Neither would be able to support the other directly.

The focal point of the French attack, the Chemin des Dames, could hardly have been a more formidable objective. The German defenses lay atop a high wooded ridge along the base of which the River Aisne followed its east-west course. The roads and railways behind the French lines almost all ran the wrong way, laterally instead of toward the front. Despite the difficulties, Nivelle proposed to overwhelm the Germans with a single crushing blow. When Joffre had first proposed a 1917 offensive, his plan had been to attack on a front of about sixty miles. Nivelle, convinced that the tactics that had worked in the final days of Verdun could be equally effective on a larger scale, had expanded that to a hundred miles. The Germans meanwhile, aware of what was coming, had increased the number of their divisions on and behind the Chemin des Dames ridge from nine to thirty-eight. Nivelle was undeterred. The more enemy divisions were on the scene, he said, the more he would be able to destroy.

Haig was skeptical, but his doubts were neutralized by Lloyd George’s disdain for him and enthusiasm for Nivelle and for his plan. Several of France’s most senior generals remained skeptical as well, but because some of them had been passed over when Nivelle was promoted to commander in chief, it was easy to attribute their objections to petty jealousy. Painlevé was so certain that disaster lay ahead that he had tried to resign from the cabinet and been refused. Now, at Compiègne, he explained his fears one final time. Again Nivelle shrugged him off. He said that if he were not allowed to proceed, he would resign. Poincaré, aware that Nivelle’s resignation would mean the fall of yet another government, hoping that the offensive would save the Russians and Italians from attack and impressed anew with his new commander’s absolute certainty, ended the discussion by telling him to proceed.

The offensive began on April 9 with an attack by four armies, three British and one French, on the northern edge of the old Somme battleground. It was intended partly to draw German reserves away from Chemin des Dames, but it was more than just a diversion. One of the hopes for it was that, if Haig’s troops broke through, they could advance to the east and link up with Nivelle’s advance. Once combined, the two forces would have enough mass to uproot Crown Prince Wilhelm’s army group and drive it out of France. As at the Somme, the British preparations had been on a colossal scale. Their dimensions are apparent in the details: 206 trainloads of crushed rock brought forward to build firm roadways behind the British front, and days of preparatory bombardment by more than twenty-eight hundred cannons and heavy mortars—one for every twelve yards of line.

Haig’s Canadians were particularly well prepared and rehearsed. Early on the morning of the attack they moved undetected to within a hundred and fifty yards of the German defenses through a maze of sewers and tunnels that honeycombed the earth under Arras. Upon emerging they were able to advance under the protection of a perfectly timed creeping barrage. The Germans, their attention fixed on the French buildup at the Chemin des Dames, had not expected anything on this scale. Taken by surprise, within a few hours they were driven off most of Vimy Ridge, which dominates the countryside east of Arras. Thereafter, the advance was slowed by wintry storms and a stiffening of resistance as German reserves came into play.

“We moved forward, but the conditions were terrible,” a British artilleryman reported. “The ammunition that had been prepared by our leaders for this great spring offensive had to be brought up with the supplies, over roads which were sometimes up to one’s knees in slimy, yellowish-brown mud. The horses were up to their bellies in mud. We’d put them on a picket line between the wagon wheels at night and they’d be sunk in over their fetlocks the next day. We had to shoot quite a number. Rations were so poor that we ate turnips, and I went into the French dugouts, which had been there since 1914, and took biscuits that had been left by troops two years previously. They were all mouldy but I ate them and it didn’t do me any harm. We also had crusts of bread that had been flung out of the more fortunate NCOs’ mess at a previous date, we scraped black mud from them and ate them. One could make two biscuits last for about three quarters of the day.”

Haig continued to attack for weeks, partly to give continued support to Nivelle, partly because the success of the first day had caused him to believe (as he was inclined to do in the middle of all his offensives) that he was on the verge of a breakthrough. But little more was gained. Entente casualties had been fairly light in the early going—almost trivial by the standard of the Somme—but as Haig persisted into mid-May, the total mounted at a rate of four thousand every day. Haig tried as usual to get the cavalry into action, but by the time this was possible the Germans were ready. Machine guns and artillery massacred horses and riders alike.

One of many

Arras Cathedral, destroyed by shelling

From a strategic perspective, the results of Arras were ambiguous. Haig had grounds for claiming success: Vimy Ridge was a valuable trophy, the Germans had had to rush in tens of thousands of reinforcements from other points along the front, and in the exhilarating first three days the British had captured fourteen thousand prisoners and one hundred eighty guns. They had also advanced between three and six miles at various points—major gains on the Western Front. On the other hand, they had achieved no breakthrough and had no hope of linking up with Nivelle. By the time it all ended, the Germans had taken one hundred and eighty thousand casualties, Haig’s armies a hundred and fifty-eight thousand. Back in London, Lloyd George was freshly disgusted by the expenditure of so many men for such limited results.

Ludendorff was alarmed. April 9 was his fifty-second birthday, and his staff had prepared a party to observe the occasion, but he withdrew into isolation soon after getting the first reports from Arras. The early British gains, the loss of Vimy Ridge especially, seemed at first to indicate that his new system of defense did not work. “I had looked forward to the expected offensive with confidence, and was now deeply depressed,” he would recall. “Was this to be the result of all our care and trouble during the past half-year?” Closer examination, however, revealed that the fault lay in the failure of the German Sixth Army’s commander to

use

the system. General Ludwig von Falkenhausen had not followed instructions. Instead he had continued to do the things that he, like all the Western Front veterans on both sides, had been learning to do in two and a half years of trench warfare. He had tried to block the Canadian advance with a heavily manned and continuous front line; instead of falling back when pressed, that line had been ordered to stand its ground and so had been overwhelmed. He had kept his second and third lines close together and near the front, so that like the first they were shattered by the British artillery and overrun. He had positioned his reserves fifteen miles to the rear, too far away to make a difference at the crisis of the attack.