A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (86 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

Veteran and newcomer

Ferdinand Foch, left, and John J. Pershing.

Ambitious as the expansion was, it did not prepare Washington for Pershing’s estimate, sent shortly after his arrival in France, of how many troops he was going to require within a year. “It is evident that a force of about one million is the smallest unit which in modern war will be a complete, well-balanced and independent fighting organization,” he reported. “Plans for the future should be based…on three times this force—i.e., at least three million men.”

None of which was of the smallest interest to Douglas Haig, whose attention was focused not a year ahead but on Flanders in 1917 and whose faith centered not on the United States but on his own ability to produce a breakthrough at Ypres. He was supported by the Royal Navy, the leaders of which saw the Belgian coast as a place where their seaborne guns could support infantry operations and as a strategic prize urgently needing to be recovered. The Admiralty had been developing plans for an amphibious invasion since 1915. By the spring of 1917, in cooperation with the army, it had begun the construction of huge floating docks capable of putting ashore infantry and tanks. Haig seized at the opportunity that this appeared to present. He and his staff developed a plan of their own, one that would combine a new offensive out of the Ypres salient with an amphibious landing and unhinge the German position in Belgium. Pressed from two directions, Haig believed, the Germans would have to give up the coast. Without room for maneuver, they might be driven out of Belgium entirely. Then, their flank exposed, they might even be forced back from the Hindenburg Line. At a minimum, the British would capture the ports of Ostend, Zeebrugge, and Blankenberge, thereby depriving the Germans of the ports from which some of their smaller submarines were venturing into the Channel. Such gains would greatly strengthen Britain’s position in any peace negotiations.

The amphibious operation was the only novel aspect of the plan. The attack out of Ypres was to be a traditional Western Front offensive: a supposedly overwhelming artillery bombardment followed by a supposedly irresistible infantry attack resulting in a breakthrough that the cavalry could then exploit. The whole thing could not have been better calculated to provoke Lloyd George, who fumed from the moment he learned of it. To him it seemed nothing more than another foredoomed recipe for throwing away thousands of lives and wrecking what remained of the new armies that Britain had been nurturing since 1914. The landing of troops from the sea, genuinely innovative though the idea was, could not be safely attempted until after the main breakthrough was achieved. To quiet Lloyd George, Haig set down a criterion for the landing. The breakthrough would be counted as real, and the amphibious force sent into action, when the British took possession of the town of Roulers, seven miles inside German territory. Lloyd George was unimpressed. He was certain that Roulers was out of reach. Haig and Robertson thought it presumptuous of the prime minister to have an opinion on such matters.

Weather, always a factor in war, had to be a particular concern for anyone planning operations in western Belgium. Flanders is an exceedingly flat geography, one almost devoid of anything more notable than scattered farmhouses, sleepy villages, and occasional patches of trees. Today, when visitors search out the battlegrounds around Ypres, they have difficulty identifying the so-called ridges and hills that the Great War made immortal; these features are rarely more conspicuous than wrinkles in a tablecloth. Flanders is also an exceptionally low part of northern Europe’s great coastal plain, so near to being an extension of the sea that its inhabitants spent centuries installing drains, canals, and dikes to bring it to the point where it could be farmed. Even today it is about as wet as terrain can be without becoming an estuary. Even in what passes for dry weather in Flanders, one has to turn over only a few spadesful of earth before striking water. When it rains—as it almost always does in late summer, and heavily—the whole area turns to mud. The composition of its soil is such that, when saturated, it becomes a bottomless, unmanageable, uniquely gluey mess.

Haig was warned. The summers of 1915 and 1916 had been unusually dry by Flanders standards, but his staff examined records back to the 1830s and reported that normally “in Flanders the weather broke early each August with the regularity of the Indian monsoon.” The retired lieutenant colonel who was military correspondent of the

Times

of London cautioned Robertson against trying to mount a major operation in the low country in late summer. “You can fight in mountains and deserts, but no one can fight in mud and when the water is let out against you,” he said. “At the best, you are restricted to the narrow fronts on the higher ground, which are very unfavorable with modern weapons.”

“When the water is let out against you”

: this must have been a reference to what the Belgians had done in the depths of their desperation in 1914, opening the dikes and inundating the countryside east of the River Yser to stop the Germans from breaking through. It was a warning that the Germans might do something similar if in similar jeopardy. It should have brought to mind yet another danger: that heavy bombardment might so wreck the whole region’s fragile drainage system as to make flooding inevitable whatever the Germans did. Haig did not brush these warnings aside, but neither did he allow them to deflect him. They made him impatient to get started while Flanders remained dry. As soon as the Arras operation was behind him, he shifted to building up an attack force at Ypres. He proceeded without Lloyd George’s approval and even though Pétain had advised him (a warning never communicated to Lloyd George) that his plan had no chance of success.

Haig hoped to prepare by establishing a new strongpoint on the edge of the salient, some piece of relatively high ground that, once reinforced, could serve as an anchor for troops moving forward to pry the Germans out of their defenses. In this connection he was given a magnificent gift by one of his army commanders. General Sir Herbert Plumer, a pear-shaped little man with the bristling white mustache of a cartoon Colonel Blimp, had been commander of the Second Army on the southern edge of the salient for two years—two terrible years during which the fighting at Ypres had accounted for fully one-fourth of all British casualties. In 1915 Plumer had begun a tunneling program aimed at the German positions opposite his line, and in 1916 he expanded it into the most ambitious mining operation of the war. Twenty shafts, some almost half a mile long and many of them more than a hundred feet deep to escape detection and drained by generator-driven pumps, were extended until finally the diggers were beneath the Messines Ridge, from which the German artillery spotters had long enjoyed an unequaled view of the area. One of the mines was discovered and destroyed by the Germans, but by May the other nineteen were finished, packed with explosives, and still unknown to the enemy.

At 3:10

A.M.

on June 7, after a week of bombardment by the heaviest concentration of artillery seen on any front up to that time (Plumer had a gun for every seven yards of front), the mines were detonated. All nineteen went off nearly simultaneously, sending the entire ridge into the air. Tremors were felt in London—Lloyd George himself heard a faint boom while working through the night at 10 Downing Street. “When I heard the first deep rumble I turned to the men and shouted, ‘Come on, let’s go,’” a lieutenant with a British machine gun corps recalled. “A fraction of a second later a terrific roar and the whole earth seemed to rock and sway. The concussion was terrible, several of the men and myself being thrown down violently. It seemed to be several minutes before the earth stood still again though it may not really have been more than a few seconds. Flames rose to a great height—silhouetted against the flames I saw huge blocks of earth that seemed to be as big as houses falling back to the ground. Small chunks and dirt fell all around. I saw a man flung out from behind a huge block of debris silhouetted against the sheet of flame. Presumably some poor devil of a Boche. It was awful, a sort of inferno.” A private, a member of a tank crew, got a closer look at the devastation. “We got out of the tank and walked over to this huge crater. You’d never seen anything like the size of it, you’d never believe that explosives could do it. I saw about a hundred and fifty Germans lying there dead, all in different positions, some as if throwing a bomb, some still with a gun on their shoulder. The mine had killed them all. The crew stood there for about five minutes and looked. It made us think. That mine had won the battle before it started. We looked at each other as we came away and the sight of it remained with you always. To see them all lying there with their eyes open.”

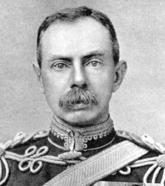

Sir Herbert Plumer

Found the key to Ludendorff’s new system.

Plumer’s infantry took possession of the long chain of seventy-foot-deep craters that now gaped where the ridge had been. It had been a spectacular success, one that achieved its objectives in minutes at almost no cost in British lives, but it was also distinctly limited. The British penetration was about two miles at its farthest point, and no effort was made to push deeper. Haig, interested in the operation only insofar as it contributed to his preparations for a main assault that was still more than a month in the future, had ordered it stopped as soon as the ridge was taken. His reasons were not trivial: he did not want the Second Army so far forward that his artillery could no longer protect it, and he did want it to dig in before the Germans could counterattack. Still, for a few hours there had been an opportunity to cut deeply into and possibly even through the broken German defenses, and that opportunity was not put to use. Perhaps the most important consequence of Messines Ridge was the taste it gave Plumer, a capable commander, of the advantages of a limited attack.

Haig still did not have London’s approval for his main offensive, and the success at Messines Ridge (which had, in the end, left the British still confined inside the old Ypres salient) had done nothing to ease the prime minister’s doubts. Lloyd George summoned Haig to a June 19 meeting with his recently created Cabinet Committee on War Policy to explain his plans in detail. Robertson also attended. Like Lloyd George one of those “only in America,” up-from-nowhere figures who appear in almost every nation in almost every generation, “Wully” Robertson was a genuinely remarkable individual, especially for the class-bound society that Britain was a century ago. Born in humble circumstances in 1860, he had joined the army at seventeen. (“I shall name it to no one for I am ashamed to think of it,” his mother wrote him when she learned of his enlistment. “I would rather bury you than see you in a red coat.”) He did well during ten years in the ranks, was changed by a commission from the army’s youngest sergeant major to its oldest lieutenant, and during long service in India mastered an array of languages, including Gurkhali, Hindi, Pashto, Persian, and Urdu. He served with distinction in the Boer War and returned to England to become both a reform-minded authority on military training and an expert on the German army. To this day he remains the only Englishman ever to rise from private soldier to field marshal (a rank he was given at his retirement, along with a baronetcy), but throughout his career he never attempted to shed the rough Lincolnshire accent that made his origins clear to all. From early in the war he had been committed to victory on the Western Front (opposing, among other alternatives, the Dardanelles campaign), and since his elevation to the lofty position of chief of the imperial general staff in December 1915 he had been Haig’s most important supporter. This made him deeply suspect in the eyes of Lloyd George.

The London conference went on for three days and was a contest from start to end. Haig laid out his plan and the great things he expected it to accomplish. Lloyd George peppered him with questions. He wanted to know why the generals believed a Flanders offensive could succeed this time, what their estimate of casualties was, how the enemy’s forces were disposed, and what the consequences of failure might be. He made it plain that he was not satisfied with the answers. The Royal Navy was called in and, to no one’s surprise, sided with the soldiers. Admiral Jellicoe, the semidiscredited semihero of the Battle of Jutland, raised Lloyd George’s furry eyebrows by asserting that Britain would be unable to continue the war for much more than another year unless the Belgian coast was taken. This warning was far-fetched (only a small number of Germany’s smaller submarines was based in Flemish ports) but so purely speculative that neither Lloyd George nor anyone else could prove that it was wrong. All the representatives of the army and navy were impatient with Lloyd George and offended by what they saw as his meddling. The cheek of this craggy Welshman, a man utterly lacking in military training or experience, seemed to them ludicrous and offensive.