A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (88 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

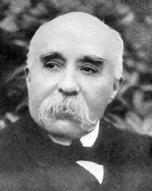

Premier Georges Clemenceau

“Home policy? I wage war!

Foreign policy? I wage war!”

Not surprisingly, French officialdom regarded him as an impossible man. “So long as victory is possible he is capable of upsetting everything!” Poincaré said early in the war. “A day will perhaps come when I shall add: ‘Now that everything seems to be lost, he alone is capable of saving everything.’” It was perhaps the most prophetic statement of the war. It reflected the fact that, regardless of how many enemies Clemenceau had made and how much his enemies resented him, it was impossible to question his patriotism, his ability, his hatred of Germany, or his commitment to victory at any cost.

He had been a singular character from youth, and life had made him more so. The son of a provincial physician who served time in jail for his outspoken criticism of the Second Empire, Clemenceau shaped himself in his father’s image: radically republican, antimonarchist, anticlerical, cynical and scornful of the whole French establishment. He completed medical studies but afterward went to the United States, arriving while the Civil War was in progress and remaining for four years. He supported himself as a teacher and correspondent for French newspapers and married a nineteen-year-old American girl named Mary Plummer, who had been his student in Stamford, Connecticut. (The marriage, the only one of Clemenceau’s long life, produced three children but ended unhappily after seven years.)

Back in France and living in Paris in 1870, when Napoleon III was captured by the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War, he was already prominent enough in leftist politics to be appointed mayor of the eighteenth arrondissement, working-class Montmartre, after radicals seized control of the city. From there he went on to serve in the Chamber of Deputies, to write for and found radical publications, and to champion such causes as separation of church and state and the rights of miners and industrial workers. Among his passions was one that alienated him from the Jaurès socialists who might otherwise have been his best allies: military preparedness. He regarded the loss of Alsace-Lorraine as an intolerable humiliation and renewed war as not only inevitable but desirable, the only way of putting things right. “One would have to be deliberately blind not to see,” he wrote, “that the [German] lust for power, the impact of which makes Europe tremble each day, has fixed as its policy the extermination of France.”

Clemenceau gloried in opposition, and for many years he led one of the Chamber’s many factions. He regarded the middle classes that dominated French politics, the most respectable people in the country, as enemies of progress and justice. During the years of conflict surrounding the Dreyfus case, in which the leadership of the French army was exposed as having knowingly sentenced an innocent Jewish army captain to a life of penal servitude for allegedly selling state secrets to Germany, Clemenceau led the coalition that broke the power of the conservatives and brought the government and the military under republican control. He had repeatedly refused ministerial appointments, but in 1906, with antagonism between the multitudinous factions causing one government after another to fall in quick succession, Clemenceau consented to become minister of the interior. In this position he surprised and delighted the conservatives by using the army and police to subdue striking miners. Though he continued to advocate the eight-hour day, the right to unionize, accident and old-age insurance for workers, and a progressive income tax, the socialists from that point on regarded him as untouchable. But his unexpected firmness won so much support from the center that later the same year he became premier. His government lasted almost three years—itself an achievement. It affected the course of the war to come by strengthening France’s Entente with Russia (which Clemenceau saw as vital to survival, though he professed to despise the tsarist regime) while laying the foundations of her secret alliance with Britain.

As the Great War became years old and the costs mounted and victory seemed more and more distant, the legislature separated into two irreconcilable camps. On one side were those who believed in the possibility of negotiating an acceptable peace. This group was led by the same Joseph Caillaux who would have become premier in the summer of 1914 if his wife had not chosen that moment to buy and use a pistol. The other, convinced that no peace could be tolerable that was not preceded by the defeat of Germany, lined up behind the Tiger.

The Chamber was so polarized that it became impossible to put together the kind of coalition with which France had been muddling through. War Minister Paul Painlevé became premier in September 1917 when the six-month-old Ribot government fell, but within weeks he too was tottering. The socialists were indignant about sudden food shortages, the conservatives bewailed the state of the army and the war, and in November the Bolshevik takeover in Petrograd shocked everyone. Painlevé, neither experienced nor skillful enough to manage it all, had to go. Poincaré as president had to find someone to form a government. At this point only two men could have done so: Caillaux or Clemenceau. Selection of the former would have meant a search for compromise with the Germans. Clemenceau, by contrast, represented la guerre à l’outrance, total war to the end. For Poincaré, the choice was obvious.

The new premier brought many advantages to the job. He knew America, spoke English, and was almost the patron saint of the alliance with Britain. Best of all, from the perspective of the conservatives who were now his strongest supporters, his first term as premier had proved beyond doubt that he was no socialist, that under his administration France need not fear Bolshevik contamination, that he would use any means necessary to maintain order. He had become the establishment’s Tiger, and from the day he took office he behaved more tigerishly than he ever had in his life. He took charge completely, filling his cabinet with capable but minor figures who lacked a political base from which to challenge his authority. Instead of naming a war minister, he took that position himself and made it plain to the generals that he, not they, would have the final word. Ironically in light of his own history, he suppressed publications that questioned government policy. Dissenters were sent to prison. Stunningly—years later Clemenceau would express some remorse about this—even Caillaux was charged with disloyalty and put behind bars. Clemenceau embraced the elites—the bankers, the manufacturers, the leaders of the haute bourgeoisie—that he had reviled all his life. Talk of limiting or confiscating excess war profits was extinguished as completely as talk of a compromise peace. The moneyed classes could help to win the war, and therefore they were Clemenceau’s friends. Anyone expressing doubt was his enemy.

Making decisions was easy in the Clemenceau government. Whatever could contribute to victory was done. Whatever might make victory more difficult was, whenever possible, stamped out. Anything irrelevant to the war no longer mattered.

“Home policy?” Clemenceau declared when questioned about his plans.

“I wage war! Foreign policy? I wage war!”

Chapter 30

Passchendaele

“Blood and mud, blood and mud, they can think of nothing better.”

—D

AVID

L

LOYD

G

EORGE

J

uly was exactly half finished when the British began their bombardment in advance of the great offensive that Haig had been waiting so long to undertake at Ypres. In intensity and duration the barrage dwarfed what the Germans had done in opening the Battle of Verdun, dwarfed what the British themselves had done at the Somme almost exactly a year before. Along fifteen miles of front, more than three thousand guns, more than double the density at the Somme, began pouring a day-and-night deluge of high explosives, shrapnel, and gas onto the Germans opposite. During the two weeks ending on July 31 they would fire four million rounds, a hundred thousand of them gas, compared with a mere million during the Somme preparation. These shells had a total weight of sixty-five thousand tons and would inflict thirty thousand casualties on the German Fourth Army even before the British infantry was engaged.

The landscape, already a barren expanse of shell holes and rubble, was rearranged again and again and again, burying the living while excavating the dead. Not incidentally, the rearrangement process destroyed what remained of the area’s intricate drainage system. If rain came—and rain was almost certain to come to Flanders at this time of year—there would be no place for the water to go.

Douglas Haig was now in much the same position that Nivelle had put himself in earlier in the year: proceeding in the face of alarmed skepticism (Foch had called Haig’s plan “futile, fantastic and dangerous”) and refusing to be dissuaded. His goal, once the infantry and the tanks that had been assembled for the offensive went into action, was to drive the Germans back at least three miles on the first day, fifteen miles in eight days. As soon as the railway junction at Roulers had been captured, a meticulously trained division with its own tank force was to be landed on the coast behind the German lines. The Fourth British Army, positioned near where the River Yser enters the sea, was then to move eastward under the protection of the Royal Navy’s shipboard guns and link up with the landing force. The Germans, at the end of their strength, would not have enough troops to form a new defensive line once they were forced to withdraw from the coast.

That was the plan. One of its problems—by no means the only problem, but one of the most serious—was that the Germans knew what was coming. Haig appears to have resigned himself to the impossibility of concealing anything except the amphibious landing, which was put under such tight security that the men training for it in the Thames estuary on the north side of the Channel were not allowed to write home. The Germans, from the air and from their observation points on the low ridges circling Ypres, had a clear view of the gathering of the greatest concentration of soldiers and weapons in the history of the British army. And of course they reacted. Fourteen German divisions were transferred to Ypres, four of them from the Eastern Front, while the British were making ready. A week after the Germans were blown off Messines Ridge, Ludendorff sent Fritz von Lossberg, the originator of the new system of flexible defense in depth, to Ypres as chief of staff of the German Fourth Army. This gave Lossberg more than fifty days to prepare. As he did so, the confidence of the German commanders grew. “My mind is quite at rest about the attack, as we have never possessed such strong reserves, so well trained for their part, as on [this] front,” Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, head of the army group in Flanders, observed in his diary.

On July 10 the Germans had launched a preemptive raid on the Yser bridgehead from which the British Fourth Army was to move eastward to join the landing force. This raid, in addition to driving most of the British back to the west side of the river, led to the discovery of a tunnel they had planned to use to blow up key German positions at the start of their advance. The discovery confirmed that something big was being planned for the coast, and the Germans’ capture of the high ground (high as such things are measured in Flanders) just east of the Yser left the British in a far less advantageous position.

On both sides the preparations were on the vast scale that industrialized total war was making commonplace. Just the construction of the concrete pillboxes that were Lossberg’s first line of defense and the underground bunkers being installed behind the lines to shelter his counterattack troops required a seemingly endless supply of gravel. It was purchased in Holland and carried across Belgium on a stream of trains.

Hanging over everything was the question of whether, his enthusiasm notwithstanding, Haig was preparing anything really different from what the generals of the Entente had been trying without success since the end of the Battle of the Marne. Lloyd George thought not. Winston Churchill thought not as well and said so. Lloyd George had appointed him minister of munitions in July, and though at the insistence of the Conservatives he was not allowed to join any of the government’s key war committees, he never hesitated to express himself on policy matters. Pétain, no less than Foch, also thought not. If the immensity of Haig’s resources justified his confidence, if his barely concealed contempt for the French made him feel certain that he could succeed where Nivelle had failed, the bloody futility of all previous Western Front offensives provided equal justification for the doubts of the skeptics.