A Young Man's Heart (12 page)

Read A Young Man's Heart Online

Authors: Cornell Woolrich

“We are all holding our breaths,” she said, “to see what beautiful new dress your wife will wear at the dance this Saturday night.”

“I don’t think she has any new ones left,” he said absent-mindedly, staring over her head into the middle of a potted palmetto.

“I’m sure she must have some hidden away that even

you

don’t know about. I know she wouldn’t be cruel enough to disappoint us.”

“Her public,” he echoed, striking an egotistical pose as he remembered having seen someone do in New York.

“Even we poor women admire her taste in clothes,” she went on, “and that’s saying a lot, you know, envious creatures that we are.”

“Oh, no, I wouldn’t say that,” he protested gallantly, hardly knowing what he was saying at all.

This matter disposed of, he mounted the stairs two at a time, giving the impression of having just escaped from something unpleasant, and threw open the door to the room with a suddenness which made Eleanor rear upright. She had been lying crouched on the bed with her hands pressed to her eyes.

“This entire place is getting impossible,” he said. “The sooner we leave—”

He thought there was a touch of guilt (Had she been crying? But that couldn’t be, what was there for her to cry about?) in the strained gayety she at once assumed, and the mocking bravado with which she undertook to answer him.

“Absolutely not,” she said, “until after I have stunned them with that mauve velvet I got at Worth’s. Once they’ve seen that I don’t care where we go.”

“You too?” he lamented. “That’s all I’ve been hearing on all sides. You seem to have turned into a sort of clothes-horse for everyone to stare at.”

She laughed and, disturbed, he thought he detected a note of vindictiveness in her laughter.

“Poor souls,” she said, “what have they been telling you now?”

And on Saturday evening, during the cloistered hour from nine to ten, as he sat watching her touch the stopper of a perfume bottle to each pulse, he remarked: “Eleanor, is that your only reason for staying, just to show them how well you can dress?”

He said it almost as though he were detached from her, and pitied her and sympathized.

“No,” she flared, “I’m madly in love with Serrano, and a dozen others. Say it, why don’t you?”

He smiled a little at that, and she caught the smile in her tale-bearing glass, which served her so well at times, and perhaps caught a little of its meaning too. Her upturned wrist remained stationary before her for a fleeting instant with the glass stopper held against it, as though she had forgotten what she had been doing only a moment previous.

“You shouldn’t put ideas like that in my head,” he said lightly, wagging his finger at her.

She said nothing.

And several hours later one of the female jackdaws downstairs awoke him to the fact that she had been carrying on a conversation with him at all by a single remark skillfully interpolated into the web of inanities she had been patiently spinning for his benefit. “I wonder where Mr. Serrano can be to-night? It’s the first time I’ve known him not to be here of a Saturday evening.”

And then, “You looked lovely to-night,” Blair told Eleanor afterwards.

“Did I?” she said discontentedly. “I don’t know. Velvet doesn’t seem the right thing for this climate.”

Genaro as he looked in September 1928 when he was in his middle to late fifties. The woman is Esperanza Pinon Brangas, the mother of Genaro's daughter (and Cornell Woolrich's half-sister) Alma Woolrich de Gonzales.

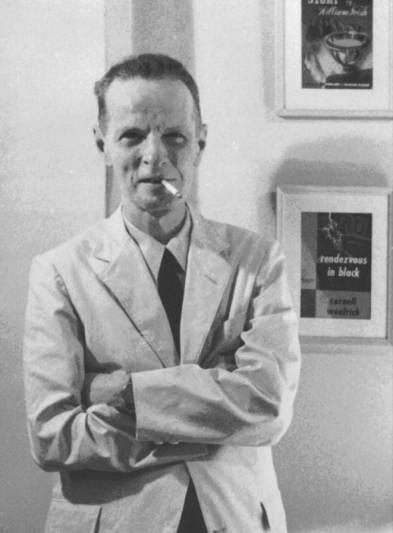

Cornell Woolrich as he looked in the middle to late 1950s when he was roughly the same age as Genaro in the photo on the opposite page.

CHAPTER FIVE

Her Admirer

1

Their

protracted and no longer very dulcet honeymoon had now entered its fourth month, and so far any mention of a return to New York had been on Blair’s part alone. Eleanor’s days and nights had gathered a momentum that seemingly robbed her of any desire to leave. She was like a little girl at a party, loath to give it up and let herself be taken home. It was inexpensive, she protested, ‘“and so much fun. It would cost us twice the amount in New York we’re spending here.” And Blair, who had himself once felt, far more deeply than she ever would, unspeakable desolation at being made to leave this very place, could understand and exonerate her reluctance to tear herself sway, and could set common sense and his own wishes aside and defer

to

hers by staying on.

Not that he was altogether blind to the motives underlying her preference; allegiance to a place where even the language was still as much of a mystery to her as on the day of her arrival could not fail to strike him as being somewhat artificial at best and grounded on more personal reasons. As a boy it had been beauty and the drowsy charm of life that had appealed to him most here. As a grown woman, he could not help feeling, the attraction she responded to must be somewhat less catholic. There was only one beauty she recognized and that was her own and that of other women. Flowers were beautiful, yes, but only after they had become a part of her by being worn on her person and exciting the admiration of others. In themselves, as entities growing in a garden, for instance, they were simply so much vegetable matter. Music too was beautiful (“sweet” she liked to say of it), as a background for her smartly shod feet, as an accompaniment to some graceful movements on her part, or as an excuse for a transient dreamy mood between two sips of tea. Other than this, and well he knew it, music held no meaning for her. Sounds made by instruments, noises she did not understand and was not interested in. Where then, he wondered, could the beauty be that made her want to linger, that held her here, purring content and basking in her own loveliness and appeal? Certainly not where he had once found it. As for the drowsy charm of life, it was simply non-existent in Eleanor’s case.

Romance was in the air here. And the Latin worship of women, built on a false premise in the first place and invariably discarded when its purpose had been served in the second, had made an irresistible appeal to her, the more so that she was one likely to excite it even in strangers passing her on the street. Yes, he assured himself, the real reason for her wanting so very much to stay on was that she had unexpectedly found a perfect setting for all her gifts. In New York she would have been one of a thousand young things, exuberant, lovely, bewitchingly golden-haired, nothing more. Here she had found a shrine waiting for her and she had stepped into it. No wonder he found it far from easy to persuade her to step out again and go back to where she could only be one of many, to where more thought was given to making money than paying spoken and unspoken homage to terrestrial madonnas who were not meant to lift their little fingers unassisted (until their marriage, that is, after which, if their virtue had been so far proven, care was taken for its continuance by shutting them up in the Moorish seclusion of houses with barred windows, from which they only emerged at intervals in the company of servant-girls and market baskets). Here she had earned the distinction of adjectives. Here she was “that little Mrs. Giraldy” and “pretty little Mrs. Giraldy.” What other things were said to her when he was not with her, he had no means of knowing. He felt sure however that there were other, various Serranos in the offing. He noticed that she had developed a most laudable technique in dealing with them. If she had at any time been even unwittingly surreptitious, which he had no reason to believe, she was certainly no longer so. Sitting on the edge of their bed late of an evening she now confided, with touching openness, whatever trifling breaches of decorum she had been made the victim of. “So-and-so keeps looking at me all the time. I hardly even know him!” She had discovered that a flirtation could be carried on much more satisfactorily under her husband’s eyes than behind his back. Moreover, its innocence was thereby at once established beyond question. She could derive the same pointless satisfaction without any attendant feeling of guilt. And it was obviously only too easy for her. In Eleanor, a certain tone of voice, an unpremeditated little gesture (which

surely

she could not have intended to convey anything by) and above all that elfin glee she displayed toward anything irrelevant (“Look at that crack in the sidewalk, it’s just like the letter Z!”) intoxicated certain temperaments just as effectively as notes, whispers, meaningful glances and stolen handclasps would have on the part of someone else. In other words, she was probably far more discreet alone than when in Blair’s company.

She had established herself in the graces of the critics, too. The hotel tabbies had reversed their original estimate of her. She was now generally regarded as a martyr to her looks. In an attempt at sex-solidarity which she would have been the first to laugh at had she known about it, they sympathized with her among themselves and unassumingly did their best to protect her against the presumptuousness and unsought attentions of insincere males. And the fact that she had at last reached the end of her inexhaustible wardrobe and was beginning to repeat on certain items of attire made it easier to like her. At least she was now on more of a parity with the rest of them; they no longer felt they had a Mrs. Nash in their midst.

2

There was a canal, straight as an arrow and cut deeply into the rich, yielding earth; filled to the brim with stagnant jade-green water and flanked by eucalyptus trees that cast their shadows over it like telegraph poles. It led from town out to the Jockey Club, which was on an island in the middle of a lagoon. Over the unruffled silky water a launch glistening with sun-smitten brass and polished enamel cut its way early on a Saturday afternoon, with Eleanor and other friends of Serrano’s choice seated under its flaunting blue and orange awning. Eleanor sat apart, with Blair at her elbow, holding the old-fashioned kind of a fan that spread and folded and coughing slightly in the benzine fumes. Blair lowered his wrist and trailed his fingers through the bubbling froth, warm in the afternoon air.

“What time is it now?” she said. “Will we be there soon?”

“Oh, God,” said Blair from the depths of his soul, “I hope so!”

As they emerged from the stagnation of the lily-breeding canal into the sparkle of the lagoon, which was like a huge open goblet of Chartreuse, the earth and the trees fell away from them on either side until the world was vastly simplified; it consisted of nothing more than two surfaces pressed face to face, sky and water, and midway between the two all unaware of the immensity of his insignificance, was Serrano with a brandy at his lips.

Blair drew his glistening fingers in out of the water and sucked them meditatively. His cheeks made a popping sound. He dried his fingers on a small handkerchief he had with him, laying them in it two at a time and pressing the free edges over them with the thumb of his other hand. He did all this with an air much older than his twenty-three years. When he was through he crunched the handkerchief into a small ball and threw it deliberately out of the boat. It took the water with the merest accent of a splash around its edges, like silver fringe, and slowly proceeded to open like one of those Japanese paper chrysanthemums cast into a child’s bathtub. The boat outdistanced it at once and it passed from view, one more thing in life. He realized he had no other handkerchief with him that day.

The squat white casino of the Jockey Club, copiously glassed, came dancing headlong over the water to meet them, growing larger and wider with every instant. Two negro stewards in freshly-laundered coats who were standing on the landing steps just beyond reach of the animal-like lapping of the tongues of water, increased proportionately in dimension, like genii out of a bottle, until their faces, which resembled two Congo masks, were in focus.

There were numerous little tables, unoccupied without exception at this early hour, set out under the open sky, while still others were within the shelter of the building itself. The whole place, both inside and out, was garlanded by an overhead network of electric globes; some were transparent and others coated an indistinguishable neutral tint that was probably either red or blue once it was lighted from within.

The party disembarked with cries of feminine gayety predominating, and dispersed about the place in twos and threes. Eleanor was the last to leave the boat, with her arm encircling Blair’s waist. But if her chagrined host seemed to have emancipated himself from all the ordinary attentions and courtesies due her, she was not entirely neglected. The manager of the Jockey Club himself, who had so artfully seemed unconscious of her very presence in their midst on the way across the lagoon, singled her out now that they were less conspicuous. He was a swarthy diamonded man not unguilty of mixed blood, who was by way of making a considerable fortune out of his resort, since the overhead expenses were almost negligible and it was beginning to give unmistakable indications of popularity. And yet he was only now being weaned by his well-wishers from a penchant for wearing pongee silk shirts with his dinner coats. Laughable as this may have appeared, it was not looked upon as unpardonable to any degree; the laxity of a semi-tropical climate and of a thoroughly undermined caste system permitted that and more.

Eleanor was leaning the small of her back against a stone balustrade overlooking the coppery-green water when he came up to her. Her chin rose a little higher in the air.

“And how do you like all this, Mrs. Giraldy?”

She said, “You can congratulate yourself this place will be a great success in a short while.”

He upturned the flat of his hand carelessly, with a gambler’s gesture. “That may be.” All the while he seemed desirous that a thread of the personal trace itself through their speech. “You must come out here often, you and your husband. The place is yours.”

Blair moved away from them.

A long narrow table had been made ready out in the garden, loaded with ferns and carnations. The waning sun, which still stood high above the surface of the lagoon but was already quite bearable in the eye, tinted the glasses and the carafes peach and porphyry-pink. Blair helped himself to an olive from a dish of brine. A lady who stood next to him, noticing this, smilingly did likewise.

The party arranged itself at table, the women first in alternate seats, the men then stepping in and filling the vacant places. Their host on his part had maneuvered to secure Eleanor Giraldy at his right hand. Blair suddenly found himself separated from her by almost the entire length of the table, and quite out of earshot. He sulked. The next moment he looked beseechingly at her, in an attempt to catch her eye. She was so far away she did not see him; she was smiling. Blair took it that she was agreeably amused.

Finally she saw him looking at her and threw a flower over, which struck him across the mouth. “Eat,” she commanded. He hated her for throwing at him that way; it was a mark of disrespect. He picked the flower up and broke the stem in half with considerable resentment. Serrano glanced over to see who it was she had thrown at, and then immediately applied himself to her again more than ever. Suddenly Blair found himself intensely jealous of the two of them, an attitude he had never experienced before in quite this fashion. Time and again he had been agonized over Eleanor when she absented herself, but no other person than Eleanor had ever entered into that feeling. Now it was different. All he knew was that he wanted to protect her for himself. It was immaterial that the world in general was one prolonged erotic mêlée. He saw this person who belonged to him menaced, and instinctively recognized the menace for what it was.

Serrano loaded her with attentions. His white teeth flashed a never-ending smile; his eyes were leeches that could not be made to forego her.

By slow degrees Blair became sick. His stomach turned. He wanted to get away from the endless dishes of food that were being served, but to get away quickly, quickly. The noxious odor of the carnations penetrated his nostrils and rose to his brain like a fiercely keen knife thrust through ligaments in the back of the eyes and nose. Bread and carnations and wine; dirty brown wine with gold dust sprinkled in it and rising again to the surface of each glass, bead by bead, like golden bees on a wallpaper design. Bread and carnations and wine. Whirring white and yellow discs appeared before his eyes. He fell over sidewise without tipping the chair, and after he had slipped to the ground the empty chair remained in place.