A Zombie's History of the United States (16 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

The Deathodists settled in upper New Mexico, and founded the city of Death’s Door. Reynolds eventually determined that it was their duty to enact God’s will and purify the world; in other words, making everyone a hybrid, a chosen one. They started forcefully converting neighboring Indians and unfortunate Americans traveling westward. Enough reports of such incidents made their way to Washington, D.C., that when the Second Cleanse began its grand sweep across the West, Death’s Door was one of the first places they visited. A weeklong raid in May 1884 saw the U.S. Cavalry raze the town and terminate the entire Deathodist population.

Purportedly there are still some 21st-century hybrids who practice Deathodism in secret, though nothing has ever been officially documented.

Regardless, rumors circulated that the zombies had been pushed in the direction of Gunnison’s men by orders of Brigham Young and the Mormon’s alleged secret militia, the Danites. Some of Gunnison’s surviving men later claimed that many of the zombies were either Carries or, possibly, Mormons dressed as zombies. These stories circulated wildly in the press and were believed by a great many.

What the Mormons would have gained by such actions is unclear. Believers of the story claimed that leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) thought that the railway would bring too many non-Mormons to their area. However, LDS officials had repeatedly petitioned Congress for both railroad and telegraph lines to pass through the region, and Brigham Young later sought an exclusive labor contract with Union Pacific to hire Mormon workers. So it seems somewhat counterproductive for the Mormons to have sabotaged Gunnison’s surveying mission.

Despite what befell Gunnison, progress was not to be stopped. Other surveying parties were dispatched, detailed maps were made, and a route for the railway was determined. Much of the construction was done by recent Irish and Chinese immigrants, all of whom were completely unprepared for life among zombies. The rail companies did not do much to help, spending little money on zombie protection. So many immigrants were pouring into the country looking for work that they were easily replaced. Even if Union Pacific had tried to keep zombies away from the workers, they would have found it nearly impossible to do, as long as the Hell On Wheels was in tow.

The now repurposed phrase “hell on wheels” was originally used to refer to the traveling assemblage of saloons, brothels, and casinos that followed the Union Pacific crew as they moved westward across the country, offering a continually available place for the workers to dump their hard-earned wages. This makeshift town would simply pack up and move once Union Pacific did, and then reestablish itself wherever Union Pacific stopped. Every type of criminal activity was to be found at the Hell On Wheels. Fights and murders happened on a nightly basis—it was a zombie mecca. In fact, Hell On Wheels eventually became such a zombie hazard that the proprietors abandoned the profitable itinerant mini-city altogether.

On May 10, 1869, Central Pacific workers from the West and Union Pacific workers from the East at last met at Promontory Summit, Utah, to drive in the final spike and join the rail lines. Union Pacific and Central Pacific kept no formal records on their workers so it is impossible to say how many were lost to the zombies, but several hundred surely met their end in a zombie’s maw. Such was the price of progress, it would seem, and the progress was monumental. On June 4, 1876, the Transcontinental Ex-press train arrived in San Francisco a mere eighty-three hours after it left New York City. Before that spike had been driven into the ground at Promontory Summit, that same overland journey would have taken months.

Front page of the

San Francisco Star

, March 31, 1880.

While the West had technically opened up following the massive land acquisitions of the previous decades, now with a safe, fast, and easy way across the country, it truly blossomed. The shape and nature of the country changed almost overnight. A journey out to San Francisco had once been a perilous one that would endanger the life of everyone involved. Now the trip could be made purely for pleasure.

Trips to the western frontier were now a leisure activity, and it became a popular pastime to shoot at zombies from a moving train. President Grover Cleveland boasted after a train ride out West that he had “felled twenty-six of the monsters in under one hour.” Despite such wanton killing, zombies got karmic revenge on trains now and again. Zombies would often step onto the tracks, getting sucked under the train’s wheels and derailing it. A single zombie ended up killing fourteen people and injuring over a hundred more when it derailed a train in Nebraska in 1882. “Zombie catchers,” wedge-shaped appendages designed to knock zombies to one side upon impact, soon became a permanent fixture to the front of all train engines. Zombies or no, nothing was going to stop the railroad.

Aside from possibly the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, no transportation network has ever shaped the American way of life more than the Transcontinental Railway.

Old West

Wyatt Earp, who was on our city police force last summer, is in town again. We hope he will accept a position on the force once more. He had a quiet way of taking the most desperate characters into custody and never were there undead seen in the streets, both which invariably gave one the impression that the city was able to enforce her mandates and preserve her dignitys.

— Dodge City Times, July 7, 1877

With rail lines snaking their way across the western country, ranchers and farmers could spread further inland and still keep trade with the East. Boomtowns shot up everywhere, and with them America’s fabled Old West, full of cowboys, land barons, bandits, and gunslingers. Over a hundred years later, children are still playing cowboys and Indians, yet none play cowboys and zombies. In reality, cowboys spent far more time fighting off and de-animating zombies than they did quarreling with the largely peaceful Indians.

While it was not unheard of for desperate, hungry Indians to make off with a couple head of cattle during the night, this was a significantly lesser danger than hungry zombies trying to make off with a couple of cowhands. Cattle drives were usually followed by zombies, which were dubbed “trailers” by the cowboys. Trailers were generally not killed, as some cowboys thought they brought good luck; a drive without at least one trailer was a bad omen. A few trailers were also good for warding off bandits that might be following the herd on its journey from the Texan ranches to the Kansas railheads, by way of the famous Chisholm Trail.

Newton, Kansas, was just an ordinary cowtown until the Santa Fe Railroad extended its line to Newton in 1871. Newton now supplanted Abilene as the terminus of the Chisholm Trail, and got all the lawlessness that came with it. Newton’s rail station had not even been functioning for a year when the deadliest gunfight in Old West history occurred on August 20, 1871.

The events that led up to the Newton Massacre began nine days earlier when two men, Mike McCluskie and Billy Bailey, were seen arguing and fighting outside the Red Front Saloon. McCluskie had arrived in Newton working on the Santa Fe Railroad as a night policeman; Bailey was a Texas cowboy who had arrived with a cattle drive. Both men had been hired by Newton as temporary Dead Headers to help de-animate the zombie trailers that would be coming in with the cattle drives all summer. The two men were constantly bickering about everything, yet people were nonetheless shocked when McCluskie suddenly shot Bailey dead on August 11 during a fistfight.

McCluskie fled town immediately to avoid arrest, but returned a few days later to “set things right.” In a testimony to Newton’s sheriff, McCluskie claimed:

I seen the bastard get bit while we was wrangling Dead but he was denying. But I seen; I seen where he got bit. Then he all covered it up with his sleeve. He called me liar. We had words. I asked to see his arm where I knew he was bit, but he wouldn’t show, calling me liar still. I said was my job to keep the Dead out and he was just gonna go bite him some folks next. Then we started swinging at each other. I knew I’d need to shoot the bastard eventually and he was landing good swings on me, so I figured I might well get it done with. So I shot him.

Newton’s sheriff believed McCluskie after an examination of Bailey’s body showed a deep bite mark where McCluskie said it would be. Meanwhile, several of Bailey’s cowboy friends, who had ridden with Bailey up from Texas, heard that McCluskie was back in town and swore vengeance, unaware of McCluskie’s zombie alibi. Later that evening the men jumped McCluskie in Tuttle’s Dance Hall, and the attack rapidly spun into an all-out gunfight when one of McCluskie’s friends jumped to his defense. In the end, five men were left dead, including McCluskie, and three more wounded. Bloodier than the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, which had only three casualties, the Newton Massacre’s legacy has suffered due to its lack of famous participants.

Also forgotten by history are the many hybrid gunslingers, outlaws, and adventurers of the American West. Gunslinging was a logical occupation for a hybrid to go into, given their ability to withstand injuries that would kill a human. What better way to win a duel than not to bother worrying if the other man shot you? The only risk was people finding out you were a Carrie, which generally resulted in a posse being formed and a pyre being built. Plenty of hybrids took the risk, though.

Probably the best remembered hybrid of the Old West was mountain man John “Liver-Eating” Johnson (the basis for the fictional character, Jeremiah Johnson). Johnson supposedly got his nickname after his Native American wife was killed by Crow Indians, which sent Johnson on a decades-long vendetta against the Crow tribe. According to legend, Johnson would pull out and eat the liver of each Crow he killed. Another story tells of Johnson’s capture by Blackfoot Indians. The Indians had Johnson tied up and left with a single guard. Johnson supposedly chewed through the ropes binding him, knocked out his guard, then took the guard’s knife and cut off the guard’s leg. Johnson lived off of the Indian’s leg while he made his journey back to safety. What is interesting is that despite the popularity of these flesh-eating stories at the time, none suspected Johnson of being a hybrid. Today we can know more conclusively, as Johnson confessed his hybridity to a friend while serving as deputy sheriff in Coulson, Montana, in the 1880s. After Johnson’s death, the friend told the truth to a Los Angeles reporter who was compiling stories on Johnson.

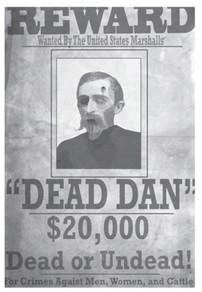

Then there was Daniel “Dead Dan” Balgoyen. Not much is known of Balgoyen’s origins. Some say he was an Irish immigrant working on the Union Pacific portion of the Transcontinental Railroad; others date his arrival in America back to the 1849 gold rush and claim he was Dutch. Whatever the case, Balgoyen wound up a hybrid, and by the 1880s had carved out a name for himself as a gunslinger and outlaw. Balgoyen was not the fastest draw, and his opponents knew it. Unlike most hybrids at the time, Balgoyen openly boasted of being a Carrie. This made few willing to fight him, as challengers knew they would need to guarantee a headshot to win. Balgoyen was known to wait until his opponents had drawn before even touching his pistol, often dueling without wearing a shirt so opponents could see his bullet-riddled torso.

Wanted poster for the hybrid outlaw popularly known as “Dead Dan,” 1886.

Balgoyen met an anticlimactic end in 1887, when he and human outlaw “Red” Jensen decided to spend the night in a barn in Madelia, Minnesota, after a successful robbery. Jensen later told the police that an animal in the barn kicked over their lantern and started the barn on fire. Jensen was able to escape, but Balgoyen became trapped and terminated by the flames.