A Zombie's History of the United States (17 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

Red Jensen and many other outlaws and gunslingers were given a second chance at legitimate work during the Second Cleanse by a U.S. Army that needed all the able-bodied sharpshooters it could find.

The War of the Dead

The only good zombie is a dead zombie.

—Gen. Philip Sheridan, 1869

Zombies had been proving an increasing nuisance to westward expansion. The more humans that entered the West, the more zombie problems there were. In 1876, the Battle of the Little Bighorn, or Custer’s Last Stand as it is popularly known, had proven calamitous and embarrassing for the U.S. Army when it was discovered that the enemy Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians had lured George Armstrong Custer and his men into a trap that was laden with zombies. Zombies were dangerous, and there was also a rising sentiment that the United States could never be taken seriously as a nation as long as it was overrun with monsters. As James Garfield succinctly put it when running for President, “Europe has no undead.” The fledgling country was simply not big enough for humans and zombies, it would seem.

The Zombie Removal Act of 1883 provided the funds needed to de-animate zombies from all United States cities. There would be no Fire Hooks this time, no pushing the zombies somewhere else. This was all-out extermination. The movement was to last almost fifteen years, and eventually expanding from U.S. cities to all the territories within the contiguous American landmass, regardless of whether a territory had applied for statehood yet or not. Today officially known as the Second Cleanse, or the Great Cleanse II, at the time many aptly dubbed it the “War of the Dead.”

There were many so-called heroes of the Second Cleanse, but none stood quite as tall as Boone Martin. During his tenure with the U.S. Cavalry, Martin personally killed more zombies than any other human in history. Initially, he had made a mark on the butt of his rifle for each kill he got, but later said he “had to stop with that ’round 200 or there weren’t gonna be no butt left.”

The moment that cemented Martin’s fame came on May 18, 1889. Martin was on a scouting mission in the Dakota Territory accompanied by two other men, Jeremiah Coy and Wallace Reede, when they stumbled upon a vast horde of zombies lurching across a basin. “Biggest mess o dead I ever seen,” Martin later recalled. As Coy and Reede readied to turn around and report their find to the rest of the company, Martin stopped them. He had other ideas. Likely already hot on his growing legend, Martin wanted to see how many zombies he could pick off. Martin rode into the horde and emptied his rifle with lightning speed. Coy and Reede followed close by, ready to take his spent rifle and hand him a reloaded one. Martin succeeded in de-animating the entire horde in roughly ten minutes, according to Martin himself, as well as Coy and Reede. Only after the last zombie was down did they notify their company. The dead count put Martin’s score for the day at eighty-seven. How accurate the ten-minute claim is, we cannot be sure. By most estimates, Martin probably de-animated more than a thousand zombies over a period of nine years before he retired from the army to join a traveling road show that offered him good money to show off his marksman prowess.

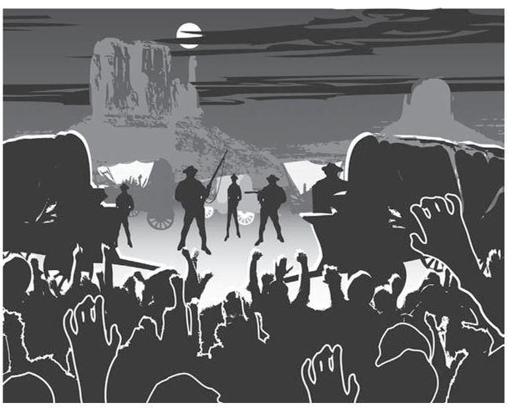

Artist’s rendering of settlers circling their wagons to act as a barrier against an approaching zombie horde.

There was not always so much glory and success during the Second Cleanse. Many encounters went in the favor of the zombies, such as the Defeat at Dubuque, Iowa, in 1887, where a horde overwhelmed the U.S. Calvary regiment, killing twenty-four. Another problem was that as the cleanse movement grew, it moved beyond the reach and control of the U.S. Army. Western towns often raised their own militias or posses to aid the cause, and groups of young men antsy for action would band together, looking to receive the cash rewards that were sometimes given for proof of a zombie de-animation (i.e., a severed head).

On August 29, 1892, a group of five men from Denver, Colorado, on a zombie hunt, stopped at the Hollenhuck family farm. The Denver group had been unsuccessful in their search for zombies—a testament to how thorough the Second Cleanse was proving to be—and had thus been out in the country much longer than they had planned. They hoped they might buy some supplies from the Hollenhucks, maybe get a hot meal, and hopefully a few leads on some zombies. Much to the group’s disappointment, the Hollenhucks informed them that there had not been any zombie sightings in the area for months. The Hollenhucks invited the group to spend the night, though regretted that they would have to spend the night in their barn. The matriarch of the family was ill and bedridden and the family did not want to risk the woman catching anything from the Denver men.

One of the Denver men, K. C. Bryant, later told the

Denver Post

:

Young Tom, son of my friend Bill, apparently had been getting eyes from one of the daughters there at the farm and had gone off to see to her after we had all gone to sleep. In the morn Young Tom were gone. The farmers said they had not seen him. Even the daughter had said so at the time. We waited, wondering where he had gone off to, but halfday pass he were still gone. Then Paddy found Young Tom’s boots and we knew something were up.

As it turned out, something “were” indeed up. Grabbing their guns, the Denver men forcibly searched the Hollenhuck house and made the grim discovery that the Hollenhuck matriarch was a zombie, zombinated quite a while ago from the looks of her. The family kept her chained up in her bedroom, as though she were still leading the farm. They found what was left of Young Tom in the room too. When Young Tom’s father, Bill, went to shoot the matriarch, the Hollenhuck family went mad and attacked the Denver men, even without weapons. During the skirmish, Patrick “Paddy” McKay, was bitten by the matriarch. This sent him into a rage. The Denver men, in their anger, ended up killing all but one of the six Hollenhucks. Linus, the surviving child, later confessed that the Hollenhucks had spent years abducting wayward travelers and feeding them to their mother.

Despite fiascoes like the Hollenhuck farm episode, the U.S. government never discouraged citizens from taking up arms to unofficially join the cleanse. The minor accidents and lives lost were well worth the greater goal of a zombie-free America.

End of an Era

Stand at Cumberland Gap and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the undead following the trail of the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by. Stand at South Pass in the Rockies a century later and see the same procession with wider intervals between… the West is now closed.

—Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, 1893

The War of the Dead had no finale. There was no zombie surrender or Treaty of the Living Dead to be signed. Officially, the Second Cleanse ended in 1897 when the U.S. military started ramping up for the Spanish-American War, but the last “battle” of any significance had occurred all the way back in 1892. Zombies were not extinct, but they were certainly endangered. One could ride for miles in the wild and never see one. In most cities, zombie attacks were now rare enough to warrant front-page news when they occurred. Canada had also followed suit in the recent decades, ridding themselves of their minor zombie population. After thriving for thousands of years on North America, the age of the zombie seemed at a close.

For most humans this meant nothing but a good thing. How could it not? But some saw it as a double-edged sword. While America gained a degree of newfound peace, it had lost an intrinsic part of itself as well. None solidified this feeling better than historian Frederick Jackson Turner. Born in Portage, Wisconsin, Turner was not a prolific writer, but he was nonetheless regarded as one of the greatest minds in American history during his lifetime. Today he is best remembered for his Frontier Thesis. The thesis was first announced in Turner’s seminal essay,

The Significance of the Frontier in American History

, which he delivered to the American Historical Association at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair.

Turner’s argument was that the root of the distinctive American character had always been the moving frontier line—which “created freedom by breaking the bonds of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities”—and the constant threat of zombie violence:

To the undead the American intellect owes its striking characteristics: that coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes from devising means which to fight and to protect against the walking dead.

During his landmark speech at the Chicago World’s Fair, Turner set up an evolutionary model: the first settlers who arrived in America were European, and thus acted and thought like Europeans. They were faced with environmental challenges different from those in Europe and most importantly, the presence of the zombies. They found themselves caught between the sophistication of settlement and the savagery of the dark wilderness, and it was the dynamic of these two conditions that forged the American being. Americans, as Turner saw it, overcame the zombies, while taking on their strength and wild natures in the process. Then generation after generation moved further inland, pushing yet chasing the zombies, and shifting the lines of settlement and wilderness, thereby preserving the necessary friction between the two. Every generation moved farther west, fought more zombies, and became more American.

The U.S. Census of 1890 had proclaimed that the American frontier was no more. The land had been tamed and the zombies were gone. Turner wondered what this meant for the character of American society. There were always new frontiers abroad to satiate America’s thirst for expansion, but there were no zombies. Zombies were an American exclusive. Though few mourned their passing.

SEVEN

Speak Softly and Carry a Severed Head THEODORE ROOSEVELT AND ZOMBIES

And to lose the chance to see frigatebirds soaring in circles above the storm, or a file of pelicans winging their way homeward across the crimson afterglow of the sunset, or a myriad zombis shambling amongst the hazy wood—why, the loss is like the loss of a gallery of the masterpieces of the artists of old time.

—Theodore Roosevelt, The Wilderness Hunter, 1893

Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt still remains our youngest president and one of America’s most iconic individuals. A warrior and a poet, a hunter and a naturalist, an athlete and an intellectual, he had the wit of Benjamin Franklin, the eloquence of Thomas Jefferson, the hardiness of Jim Bowie, and the thirst for adventure of a cowboy. He embodied the American spirit and character at a crucial juncture in our nation’s history and announced America as a world power.

Few Americans, let alone few American presidents, can lay claim to as many cultural achievements as Roosevelt: he was the first president to ride in an automobile; the first to host an African American in the White House; he inspired the teddy bear; popularized his favorite adjective “bully”; coined the phrases “square deal,” “throw my hat in the ring,” “speak softly and carry a big stick”; and adding to this long list of achievements…