A Zombie's History of the United States (2 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

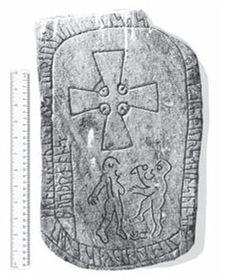

If only those first humans who found their dead rising up against them had been able to preserve their history, what grave and revealing stories they might tell us. As is, our preserved record of zombism barely goes back a thousand years. The Vikings were with all probability the first Europeans to encounter zombies. These hardy explorers kept no records either, though the Icelandic saga collection,

Hauksbók,

retains much of the Viking oral history.

Saga of Erik the Red

, which chronicles the events of Scandinavian legend Erik the Red’s banishment to Greenland, as well as his son Leif Ericson’s attempts to settle present-day Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, contains several references to a vicious tribe living in the New World, which the Vikings referred to as

óvættrs

, or monsters. It was these

óvættrs

who prevented the Vikings from establishing a permanent settlement in North America. A Norse runestone dating from the period (uncovered in Greenland in 1914) depicts a Viking fighting with an

óvættr

, who is portrayed as being badly dismembered. Surely these were zombies the Vikings clashed with there.

This Viking runestone, circa 1040 AD, found on Kullorsuaa Island in northwestern Greenland in the 20th century, depicts a male Viking battling a treacherous

óvættr

. Many scholars believe this to be the earliest known European record of a zombie.

Fortunately for us, the next round of Europeans to reach North America some five hundred years later kept fairly thorough records. Doubly fortunate for us has been the efforts of the University of Minneapolis to preserve these records.

Was Tom Ringdal’s discovery at Anadyr news to you? Had you never even heard of Thadds Michaelssen’s Asian origin theory before? Or Michaelssen himself, for that matter? Statistically speaking, the chances are you have not. Zombology and other undead studies have long been ghettoized onto the periphery of the academic world. Zombies lurch about in popular cinema and literature as pop-cultural commodities. High schoolers could easily rattle off their favorite zombie video games, yet they would be hard pressed to tell you what happened at Valley Forge or who the Carrion soldiers were. They are certainly not the ones to blame for this ignorance either.

As far back as the early 1800s, authors, journalists, so-called scholars, and even presidents of the United States, have overtly sought to whitewash zombies from the American story. Sometimes the exclusion was the product of shame, embarrassment that our country was beset by such foul creatures, and an attempt to ignore certain realities. Other times it has been outright conspiracy. Of the ten best-selling current public school history textbooks (according to the 2005 Russ-Youlin Teachers’ Poll), only two even mention zombies at all.

American Glory: The Story of Our Country

, by Jonathon Davis, does the most amiable job, including references to zombies in both the Revolutionary War and the American Civil War, but claims that the zombie contagion was eradicated by 1900.

A History in Red, White, Blue

, by Ryan and Sarah Cavanaugh, gives the impression that zombies disappeared shortly after the arrival of Europeans.

When Roger N. Pope started the University of Minneapolis’s Zombological Department in 1974, originally secluded on a dank basement level of the Minneapolis campus’s Native American Studies building, its primary goal was the salvation and preservation of important zombie texts, which were being actively destroyed by many universities at the time. Since then, with the help of people such as Hollis Meyers, Margaret Stegland, Dan Patrick, and current department head, Tom Ringdal, the UMZD has amassed a truly impressive library of crucial documentation—the most definitive on the planet. Since Ringdal’s 1993 archeological discovery, it has become a mecca for those interested in zombology. People such as myself.

I have had the great fortune to work with some of the best minds in the field of zombie history, people without whom this book would be only half what it is. Even with this collective effort, I have no doubt that much is missing. We are finding and uncovering new records and documents every year. In 2007, the Department of Defense classified volumes of previously unverifiable material, and there is surely more where that came from. This book is simply a first step, and hopefully, a first step toward a renewed awareness and interest in zombie history.

Our fear, revulsion, and hatred of zombies has caused us to try and ignore them over the years, like a collective bad nighttime experience we all wish to forget the following morning. I am not here to argue that zombies should not be feared, reviled, or hated, but simply that they not be forgotten. Not for their own sake, but for ours. The ancient Roman philosopher and historian Cicero once said, “Who does not know that the first law of historical writing is the truth?” I think we all deserve the truth, as ugly, scary, embarrassing, and disgusting as it sometimes may be.

This book is not meant to be a history of the United States. I am here to tell the zombies’s story, and nothing more. Though in doing so I cannot help but tell much of the American story too. For the story of the zombie

is

the story of America.

I think it is time for the zombie to rise again. No pun intended.

ONE

New World, New Monsters THE DISCOVERY AND COLONIZATION OF THE AMERICAS

The Indians tell a genesis tale of how their people arrived on the island. They say they were fleeing the dead.

—Bartolomé de las Casas, priest and humanitarian, History of the Indies, 1523

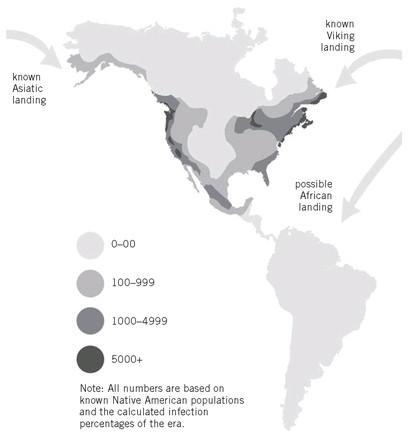

Christopher Columbus never saw a zombie. Indeed a majority of the first explorers to the New World never did, or at least never realized they had. Journals will mention passing encounters with haggard and rabid natives, but the Europeans apparently held the indigenous population in such low regard that this was not taken as out of the ordinary. Generally, zombie encounters would have been rare in the areas the Spaniards were first laying claim to. While the Aztecs and some Mesoamerican civilizations had utilized zombies for religious ceremonies and rituals, the mountainous terrain of the lower North American isthmus impeded zombism from spreading in epidemic form past the medial section of Central America.

Approximate undead population density circa 1450.

Upon his discovery of Florida in April 1513, Ponce de León had a skirmish with what were very likely zombies, though he believed the attackers simply to be very hostile Indians. If one of his men had been bitten, surely he would’ve thought differently. During Ponce de León’s final voyage to Florida, in 1521, it was believed that savage Calusa Indian braves poisoned him during an attack. His ship’s log describes the poison as inducing “furies,” noting that he “will try to bite others.” There likely was no poison. The famous explorer was quite probably the first European zombie casualty of the Age of Exploration.

A small scattering of mysterious ailments and attacks are nothing to stand in the way of conquest. Soon all the major European powers were looking to stake a claim in the New World.

The Lost Colony

Suitable placement found. Neighboring natives—possible cannibal behavior.

—Phillip Amadas, explorer, journal entry, 1584

Founded in 1587 under the patronage of Sir Walter Raleigh, the Roanoke Colony on Roanoke Island (in what is now North Carolina) was England’s first attempt to establish a permanent settlement in the New World. One of America’s most enduring mysteries was born when the expedition’s leader, John White, returned to Roanoke after being held up for three long years by the Anglo-Spanish War, only to discover the settlers completely vanished, the word “Croatoan” carved into a post of the fort the only clue.

Theories have abounded since, ranging from extermination at the hands of the Spanish to assimilation with a neighboring Indian tribe, but the best evidence all points to one simple conclusion: zombies.

In 1584, Phillip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe were dispatched by Raleigh to explore America’s eastern coast for an appropriate location to establish a colony and to foster a relationship with the local natives. They met with several tribes, including the Chesepian of the Carolina Algonquians. In his journal, Amadas notes that the Chesepians warned them from settling on what is now Hatteras Island, for it “was home to many walking ghosts,” or

croatoa,

in their tongue. Amadas and Barlowe naively presumed the Chesepians were superstitiously referring to an enemy tribe. Instead they chose nearby Roanoke Island as their ideal settlement, continuing to believe that Hatteras—or as the English referred to it, Croatoan Island—was populated by the Croatoan Indians.

In 1590, when White discovered the word “Croatoan” carved into the fort, he purportedly was unable to conduct a search of Croatoan Island because bad weather necessitated he and his crew return home. Yet White’s ship’s log makes no mention of a storm, nor the exact date of their departure. Then there is this curious passage from the diary of Timothy Hughes, an English poet and natural sciences hobbyist:

I had a most revealing intercourse the evening prior. The Man I had seen was shipmen board the Privateer went discovering for the Roanoake settlement—Subject most of interest for mineself. After liberal plying of spirits the Man altered his Story from which I was aware. He spoke of awful Men with flesh slung from the bone who gave the crew much antagony and impediment in their discovery. These devious beings were nigh beyond harm and the Crew escaped but with their Lives.

The “lost colony” tale is merely surviving propaganda. It surely did not behoove England’s interests abroad to have investors and potential colonists think the New World was overrun with horrible monsters, especially at a time when they were trying to establish a foothold on the continent. The Roanoke colonists kept no records, so it is impossible to say anything for sure, but what seems most likely is that they attempted to contact the supposed Croatoan tribe, were attacked by the zombies, and carried the zombism back to Roanoke.

The Massacre at Plymouth Rock

And for the danger it was the beasts, and they that know the beasts of that country know them to be foul and violent, and subject to cruel and fierce assaults.

—William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, March 10, 1621