Aboard the Democracy Train (14 page)

Read Aboard the Democracy Train Online

Authors: Nafisa Hoodbhoy

From my sanctuary in Islamabad, my mother told me the phone at our Karachi home rang off the hook. Government officials, politicians, journalists and, of course, friends called to ask about my welfare. Embarrassed by the negative publicity they received, officials in Jam Sadiq Ali’s cabinet offered to appoint police officials to a security post they proposed to build across from my house. It was like asking the fox to guard the chicken coop. I rejected their offer.

As I lay low in Islamabad, Benazir Bhutto issued a statement from overseas which squarely blamed the federal and Sindh government for the attacks on me and Kamran that read:

“Both journalists have a distinguished record of investigative journalism, which includes an expose of the MQM and the

criminal activities being conducted at the CIA headquarters. There is no doubt that these attacks have been coordinated by the Jam Government on the instructions of Nawaz Sharif and Ghulam Ishaq Khan.”

It was a fair indictment of the perpetrators, except that it cast doubt on the MQM’s role in the attacks. Although the ethnic party used to dictate news coverage, threaten hawkers and burn newspapers considered to be unfriendly, by the fall of 1991 they were themselves victims of the army’s “Operation Clean-up.” As such, they were not in a position to conduct the attacks.

The MQM chief, Altaf Hussein – who had fled to London earlier that year after the army tried to divide his party – attempted to clarify the perception that his party was involved. In his press statement of September 27, 1991, Altaf said:

“We too differ with some of the media contents, but we go to the people and ask them to stop reading a particular paper. The MQM has never attacked any newspaper office or resorted to such things.”

I took the MQM statement with a handful of salt. At that moment, however, I recognized that I had grown entangled in the war between the intelligence agencies.

Back then, the MI – which is the political wing of the military and which also provided me and Kamran with information – was apparently at odds with the techniques used by the ISI and the IB in arm-twisting the PPP’s political opponents. The IB’s chief, Brig Imtiaz Ahmed – whose agency snooped around to guess which journalists could expose their tactics – had put us on its “hit list,” with a directive to the local Crime Investigation Agency to ensure that we did not interfere in their mafia operations.

Five days had passed and I watched the national outcry against the knife attacks from my brother, Pervez’s place in Islamabad. That weekend, Pervez’s colleague at the Quaid-i-Azam

University, Dr A. H. Nayyar arrived, carrying heavy editions of the newspapers. Dr Nayyar – a nuclear physicist, like my brother – was hugely invested in the political situation inside Pakistan and had a wry sense of humor.

Apparently tired from the weight of the weekend editions of the English and Urdu newspapers he had been carrying, Nayyar plunked them on the table in front of us and flopped down himself.

“What’s the news?” my brother Pervez asked.

“Nothing,” Nayyar replied wearily. “They’re full of statements on Nafisa.”

I went through the newspapers. Statements were splashed across every newspaper by political parties, journalist unions, women’s organizations, minority groups and human rights groups. In several instances, they named the influential culprits and demanded punishment for the attacks on me and my colleague.

Even while the federal government assured our employers and the journalist unions that our attackers would be caught and punished, we knew that nothing of the sort would happen. The matter of free press was inextricably linked with the polarized politics in Sindh and could not be resolved short of dismissing the Sindh government. The newspaper bodies correctly surmised that the media would suffer unless we demonstrated a collective show of strength.

And so newspapers, magazines and periodicals announced they planned to suspend publication on September 29, 1991. It was an unprecedented event, designed to halt 25 million copies for one day in order to protest against the attacks on journalists. The journalist community declared that, as a mark of protest, no reporter would attend or cover the government functions on that day – a Sunday.

On the day of the press shutdown, my journalist colleagues from

The News

took me to the home of their editor, Maleeha Lodhi. Lodhi would later serve as Pakistan’s ambassador to the US under Benazir Bhutto and then Pervaiz Musharraf. Maleeha looked at me searchingly and said, “You know, Kamran is

associated with the intelligence agencies. But with you we know there is no such association.”

A journalist friend of mine, Ayoub Shaikh had once asked me, eyes twinkling, “I sometimes wonder, who does Nafisa work for?”

“No one,” I had said, “I work for myself.”

“I know,” he had said, smiling.

On the day of the strike, the Rawalpindi Union of Journalists organized a national event in Rawalpindi – Islamabad’s twin city – which was addressed by media stalwarts such as the president of the All Pakistan Newspaper Society, Farhad Zaidi, veteran journalist turned politician, Mushahid Hussain,

The News

editor, Maleeha Lodhi, senior editors and representatives of journalist unions.

I spoke in a highly charged manner, fired up by my close encounter. Mostly, I told journalists in Islamabad about the incredibly polarized political situation in my southern home province of Sindh. “If we do not stand together, I am afraid that a journalist may be killed any day now,” I said. It was a speech made from the heart and it appeared in the press on October 1, when the newspapers went back into circulation.

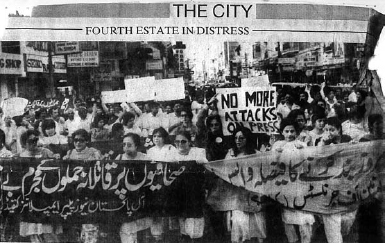

Figure 6

Karachi journalists protest attack against press on September 30, 1991 (

Dawn

photo).

A Pakistan Television team was on hand to film the rally at Rawalpindi Press Club. I was surprised to see them, wondering how the government had allowed them to film the protest. Later, watching the video footage of the nationwide protests in the districts, towns and cities – and an impressive march in Karachi from whence the attacks had emanated – it was evident that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was not entirely in charge.

I came back to Karachi, energized by the uproar in the newspapers. The ripple effects continued as column writers marveled at how the entire journalistic community had put aside its differences and united for a common cause. The newspaper industry had successfully communicated its message to the government. The attacks on journalists ended, giving me renewed courage to return to reporting.

I discovered a strange notoriety in the furor that had been caused by the attacks. Soon after the incident, as my father drove home he was confronted by the police. A traffic light was changing from orange to red when my father had passed through and the constable signaled my father to stop.

Traffic violations are extremely common in Karachi but when a police officer finally catches up with a motorist, the music begins. As my father stopped his car the policeman sauntered over, opened the side door and slid into the back. That, everyone in Pakistan knows, is the prelude to taking a bribe.

My father mischievously exploited the situation.

“Do you know who I am?” he asked the policeman.

“No” the cop replied with some trepidation.

“I am Hoodbhoy, father of Nafisa… you know the reporter from

Dawn

who was attacked recently.”

The policeman was impressed but decided to check out the facts. I was at home for lunch during my reporting assignments when I got a phone call from the police official, who had decided to check out my identity. When I confirmed who I was, he named the person with him, saying, “He claims he’s your father. Should I let him go?”

I could just see my father, with his sense of fun, testing out the policeman. Embarrassed, I demanded he be released at once. A short while later my father walked in chuckling, saying the policeman had apologized profusely for the inconvenience!

A decade after my knife attack,

Wall Street Journal

reporter, Daniel Pearl went missing in Karachi. He was on perhaps the world’s most dangerous assignment. The wounds from US retaliation against 9/11 plotters – who had been traced to Afghanistan – were raw when Pearl arrived in Pakistan to investigate Al Qaeda militants’ links to the military and multiple affiliated intelligence agencies.

I felt like I had traded places with Pearl. In 2002, I taught in Western Massachusetts, where Pearl had worked as a reporter in the 1980s. While I lived in his neck of the woods, the

WSJ

reporter arrived in Karachi to probe the Al Qaeda network, talking to some of my contacts in the city about how militants had regrouped to escape US bombardment in Afghanistan.

In a nation where the sentiment is (at best) moderately anti-US, Pearl’s timing couldn’t have been worse. In a Karachi, fast evacuated by foreigners, he stood out as an American and a Jew. Whilst the military ostensibly sided with the US, journalists who sought to reveal its covert ties with militants were treated like spies. It did not surprise me, therefore, when Pearl’s kidnapping provoked former President Gen. Pervaiz Musharraf to express irritation at the “undue interference” in the nation’s internal affairs.

Local reporters too watched Pearl’s brief foray into Pakistan with skepticism. My colleagues in Karachi knew he had gone missing but did not leap into action. Just as Pearl went missing, a former newspaper colleague of mine was picked up as he investigated the shady links of a mafia don linked to the December 2001 attack on the Indian parliament in New Dehli. As journalists built up pressure, he was released but remained uncharacteristically silent.

Although the Bush administration’s invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 brought thousands of journalists to Pakistan’s border areas, Pearl paid the ultimate price for leaving the pack. After Pearl was revealed to have been killed, I met the last person he had contacted in Karachi prior to his disappearance: former chief of the Citizens Police Liaison Committee (CPLC), Jameel Yusuf.

The CPLC chief, who often gave me scoops on political crime, told me that he had briefed Pearl about Al Qaeda’s affiliations with terrorist networks in Pakistan. However, Yusuf says that Pearl did not divulge anything about his mission in Pakistan. With his Sherlock Holmes instincts, the CPLC chief noticed that Pearl’s cell phone rang twice while he was in his office. But the intrepid reporter did not mention who called and left, saying he had an appointment.

The CPLC’s recovery of Pearl’s cell phone and perusal of his phone bills would enable them to trace his kidnapping to a British-born militant of Pakistani origin, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh. Sheikh was allegedly partnered with the sectarian Sipah Sahaba Pakistan and the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi – franchise groups linked to Al Qaeda, which had recently been forced out of Afghanistan.

Under Western pressure, Pearl’s alleged kidnapper, Omar Sheikh was arrested as he took refuge with a former Musharraf associate and former ISI official, Brig. Ejaz Shah, who then worked as Punjab Home Secretary. As the highly-connected Sheikh’s case came up for trial, the CPLC chief was threatened against testifying. Yusuf told me that Pearl’s case had forced him to adopt extra security.

“For the first time, I have been going around with an armed back-up,” he said in a voice that typically grew low when he became fierce and resolute.

In this environment where Western journalists could ill afford to take risks, Pakistan’s print journalists bravely dug in murky waters. Kamran Khan – who had escaped a knife attack along with me in 1991 – wrote an article in

The News

which linked the prime suspect behind Pearl’s kidnapping, Omar Shaikh with the Islamic militants who had attacked the Indian parliament in New Dehli in December 2001.

The Musharraf government reacted angrily to the article – which hinted at the ISI’s involvement in Pearl’s kidnapping – and stopped all advertisement of the newspaper.

The News

’ editor, Shaheen Sehbai was asked by the government to fire four journalists who were suspected as “trouble makers.” When Sehbai asked the publisher of the paper, Mir Shakil ur Rehman,

who

wanted to fire him, he was told to see ISI officials.

The international uproar that followed Pearl’s murder led Musharraf’s administration to pass the “Defamation Ordinance” which imposed a fine of PKR 50,000 (almost USD 900) and a three-month prison sentence for “libel.” For journalists who earned a pittance and had no security from their newspaper bodies, the amount was a powerful deterrent against investigative reporting in areas where the military ostensibly carried on its anti-terror operations.

While Musharraf ruled within the US sphere of influence, my forays into the border areas of Afghanistan led me to discover how journalists were alternately threatened and abducted and had their homes bombed and families harmed as they attempted to sift fact from fiction in Pakistan’s ostensible “War on Terror.” That post-9/11 period would be the most trying for journalists – caught between Taliban militants and security agencies.