Aboard the Democracy Train (16 page)

Read Aboard the Democracy Train Online

Authors: Nafisa Hoodbhoy

But there I was: a journalist turned witness. Given my background from an influential newspaper, the women had brought me along to ensure that the police filed the FIR. If the policeman failed to file the crime report and I reported the fact in my newspaper, it could have cost the officer his job. The sub-inspector looked up at us, licked his finger and reluctantly began to pen down the charges.

In Pakistan, an FIR is the first step toward bringing an accused to trial. It would help me to formally build up the case against the alleged rapist and give me the first real taste of the media’s power to influence society. I began to report every day on the nurse’s rape. The effect of daily reporting had a snowball effect. Every day I got stacks of press releases from women and human rights groups, demanding that the accused be arrested.

It is the familiar recourse that civil society has taken in the violent and unjust environment in Pakistan. Given the absence of rule of law and a weak judiciary, civil society increasingly relies on the press to make itself heard. Indeed, if statements alone could bring change then – judging by the weight of the press releases that pour into newspaper offices – the nation should have transformed by now.

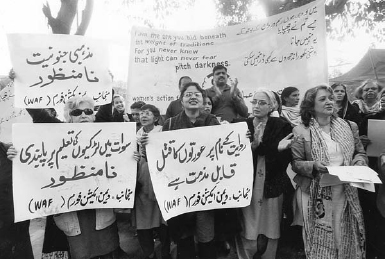

Aware that press statements alone could not change society, the Women’s Action Forum mobilized a demonstration to protest the rapes and build pressure to arrest the accused. They invited women from an Islamic fundamentalist party, the Jamaat-i-Islami to join. It was a bold step given that it was the Jamaat that had pressured Gen. Zia to pass the Islamic laws, which in 1985 were indemnified to the constitution as the Eighth Amendment.

I went to cover the demonstration feeling elevated that the protests had spilled out of my staid black and white newspaper

into the public arena. Police had cordoned off traffic on the congested M. A. Jinnah Road as women from different organizations, dressed in traditional

shalwar kameez

and

dupatta

(loose trousers with tunic and scarf), fanned out in the hot sun. Although privileged women shied away from the noisy overcrowded public places, they were out for a cause. With a dramatic flourish, they unfurled their banners in the sunlight that lighted up the dark exhaust fumes from passing vehicles.

Marching side-by-side with the elite Western-educated women were women from the Jamaat-i-Islami, dressed in black billowing veils with only their eyes peeping from underneath. Rape had united all women on a one-point agenda – arrest of the rapists. Like their secular compatriots, the Islamic women held banners and placards calling for the arrests of the rapists. For a while, all the women appeared to be united.

Suddenly, the secular Western educated women from Women’s Action Forum pulled out placards and banners that called for the repeal of the Zina Ordinances. There were a few seconds of confused silence as the Jamaat-i-Islami women saw the posters and then a cacophony of high-pitched female voices rose in protest. Banners and placards were folded by the veiled women, with a shrill protest that they were leaving. “We joined to demand punishment for the rapists,

not

for the repeal of the Islamic laws,” the women said as they left in a huff.

Figure 7

Women protest against religious fundamentalism on February 12, 2009 in Lahore (

Dawn

photo).

It is the conflicting ideologies between secular and Islamic groups that have dogged the women’s movement. The Islamic groups, which pushed for Islamization under Gen. Zia ul Haq’s military rule in 1977, keep their distance from liberal, Western-educated women in Pakistan. They term such women “

maghrebzadah

” (westernized), believing that they have failed to grasp that Islam

liberates

women and treat secular women’s organizations as fringe groups who do not grasp that Islam is the raison d’etre for Pakistan.

I had covered the press conferences of the Islamist women ideologues, where they appeared dressed in enveloping veils – revealing only their eyes or spectacles. My own

shalwar kameez

, without the enveloping

dupatta

, did not deter these Islamic women from approaching me. More than once they tried to persuade me, the unveiled “Westernized” woman reporter, to join their

jihad

to change society.

But despite shared goals of seeking a better society, I could not reconcile myself with these laws in a day and age when women’s roles had changed globally. The Jamaat encompassed a “divine” ideology that ordained women’s role predominantly as wife and homemaker. Indeed the Jamaat had been part of Gen. Zia’s Majlis-i-Shoora (Consultative Council), which formulated a spate of women-related laws that were incorporated in the secular constitution framed under Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1973.

Apart from the Hudood Ordinances, the Zia government passed the “Laws of Evidence,” under which two women’s testimony is equal to one man in financial matters. This was coupled with “

Qisas

and

Diyat

” (Retribution and Blood Money), which fixed the “blood money” (compensation) for female victims of violence at half that of men. Sections of the

Qisas

laws deny women the right to abortion under any circumstances.

Back then, the departure of the

Jamaat

women from the demonstration convened by the Women’s Action Forum left a

shrinking number of women’s organizations to keep up their lonely march for the repeal of the Hudood Ordinances

.

In 1989, the nurses’ rape case became an example of how hard women had to work in order to get a semblance of justice. As nongovernmental organizations sent press releases to demand the arrest of the culprits, I painted a sketch of the kind of people who normally got away with crimes – simply because they were rich or powerful.

The incident resonated among members of civil society who sought justice for the most unprivileged. As women contacted human rights lawyers, the latter joined in the demand for the arrest of the accused. Under pressure, the police issued summons to the accused, Khalid Rehman, to appear in court and respond to the rape charges.

The hearing in the bail application of the alleged rapist took place in the District and Sessions Court in Karachi – an impressive British colonial-style stone building on Mohammed Ali Jinnah Road. Many of those who had arrived for the rape hearings had read about the case in newspapers. The courtroom quickly filled up with lawyers, women’s rights activists and the press. Outside the court, the police stood waiting in full force.

The senior nurse, Farhat Sadiq arrived – her head covered and looking crestfallen. Accompanying her was her poor father, a Christian who worked as a low-paid sweeper. The Women’s Action Forum, which agitated on various levels against Pakistan’s controversial rape laws, had reached out to other nongovernmental organizations to mobilize them for the case. Women occupied the front rows of the court and listened intently as the state prosecutor read the statement against the accused.

The accused, Khalid Rehman, stood nervously facing the judge, his back to the women. Their presence was akin to a moral jury. But just as the judge looked up from his pince-nez spectacles to speak, the accused dashed out of the courtroom. I was seated in the same

row as the women’s rights activists and this sudden flight by the accused startled all of us. Without thinking, we spontaneously ran out of the room after the young man, wondering if this was the end. And then, the tension turned to laughter.

The police, who waited in the dazzling sunlight outside, had caught the young man by the scruff of his neck. As newspaper photographers clicked away, the accused was dragged ignominiously before the judge, handcuffed and thrown into a van full of gleeful policemen. He was driven away in a police van and locked up.

Next day, there was pizzazz in the newspaper reports that a young man accused of rape had run away from a courtroom full of women. It had turned the tables for women, who, despite being rape victims, were the first to receive unwanted publicity.

But Rehman had spent only a few days in police lock-up before he was released on bail. Women rights activists racked their brains for ways to get him convicted. They consulted with prominent Islamic lawyers to secure punishment for him and his gang. To their dismay, they had come to a dead end.

The Zina Ordinances mandated that there should be “four Muslim, male adult eyewitnesses of pious character” to obtain a conviction. Being a woman and a non-Muslim, the nurse’s evidence was inadmissible in court. Although the nurse’s lawyer told the court that medical examination of the nurse showed a broken hymen, the judge said he had no way of knowing that it was not due to consensual sex.

The nurse’s lawyer – an elderly man, hard of hearing – argued before the stony faced judge till he was blue in the face. He was being asked to do the impossible – defend a woman and non-Muslim under a law that did not hear them out. The situation took an absurd turn: the lawyer warned the rape victim that unless she claimed that the incident never happened, she would be imprisoned for having sex outside of marriage.

Alternately aghast and furious, the Women’s Action Forum raced through the alternatives. But as the case dragged on, the nurse found herself in a quagmire. She finally took the advice of her lawyer and pleaded that the incident never happened.

After 2½ years, the case was quashed with the effort ultimately unsuccessful.

Gen. Zia ul Haq took power on July 5, 1977 with a series of pronouncements that were meant to satisfy the clamor of the Islamic lobby. Barely a few weeks after his take-over, the law enforcement agencies had begun to segregate men and women.

Pakistan was then only a young country of 30 years, when the official ideology that the nation was created as a separate homeland for Muslims was exploited by vested groups. The meagerly paid policemen too found purported Islamization to be a good way to embellish their earnings.

Shortly after Gen. Zia’s military take-over, uniformed police descended on the sandy shores of Clifton beach and scoured it for unmarried couples. They swooped down on unsuspecting couples; took the sheepish male aside and threatened to lodge a case against him for abducting the girl under the Zina Ordinances

.

The couple would be let go after the police had pocketed a good-sized bribe.

In 1983, whilst still in the US, I read that a women’s demonstration in Lahore had been baton-charged for protesting against the proposed “Laws of Evidence.” Under Pakistan’s current Laws of Evidence, two women are required to testify in financial matters in place of the testimony of one man. Muslim clerics have supported the law with their interpretation of a Quranic verse taken to mean that if one woman forgets, the other should be there to remind her.

With great indignation that I read that the women who protested against the law were mercilessly beaten by police and dragged away to the police stations. Thereafter,

fatwas

(Islamic pronouncements) were issued against these women “infidels” and their marriages were declared null and void.

Incidents like these made my heart race. I longed to jump into the fray and use my writing to make a difference. Unlike Pakistan’s

intellectual elites who had studied in British schools and to some extent integrated in the prosperous West, I wasn’t particularly interested in walking on a well-trodden path. Then still in my twenties I saw myself as an actor in the wild uncharted course of politics in Pakistan, with which I felt organically connected. And so I took the less traveled road and returned home.

In February 1984, I applied for and was accepted as a reporter at

Dawn

newspaper. The “Reporter’s Room”, as the City Desk was then called, had no ventilation and the fans threw off stale air, leaving us dripping in sweat during the hot summer days. I was assigned a wooden desk with an antique typewriter that bordered the desks of senior male writers.

Being the only woman to report on city events was especially unique in an environment where Pakistan’s rape laws had forced women out of public places. Gen. Zia’s military government had already been in power for seven years and, with the help of Islamic fundamentalists, had worked to instill the fear of Allah in those who dared violate the rules. The state owned media had begun to equate women’s mere presence outside the home with licentiousness and pornography. It had emboldened ordinary people to comment loudly on women who did not wear the

dupatta

over already modest clothing.

In this backdrop, my city editor, I. H. Burney took a special delight at sending me to all-male events. Looking at me – banging away at my rusty typewriter – he once thundered in his typically witty fashion: “Just as there is one God and one Prophet, there will always be only one woman reporter.”

Often, when I arrived at a function where the speakers and reporter were male, it raised awkward questions. In the event that I occupied the press gallery, this resulted in a row full of empty seats next to me. The glances of my male colleagues told me that they were afraid that sitting next to a young woman in a period of strict Islamic military rule might get them into trouble for “dishonorable conduct.”