Aboard the Democracy Train (21 page)

Read Aboard the Democracy Train Online

Authors: Nafisa Hoodbhoy

A police team was dispatched to Jamali’s hometown in Nawabshah to recover his licensed gun and the car used for the murder. These items would never be found. Jamali was later found to have sold his car to a dealer in the tribal areas, where no one could trace it. It was clear to us that the PPP MPA could not have acted without the help of his “friends” in government. Over a month had passed since Fauzia’s murder and the sole accused from Benazir’s party was nowhere to be found.

While covering the Sindh Assembly on my regular beat, I seized on the opportunity to confront PPP Sindh Chief Minister Syed Qaim Ali Shah as he addressed a regular press briefing on the law and order situation in Sindh.

The short, thin and balding party loyalist had won a landslide victory in Khairpur, which I had visited a year ago. Now, I asked him, in his capacity as chief minister, how long his party man and fellow parliamentarian could remain absconding for murder. Pen in hand, my fellow journalists sat poised to note his response. Shah pursed his lips and frowned, as he did whenever he grew thought hard. Looking at me in the eye, he said that police had been directed to arrest Jamali wherever he was hiding.

As Karachi burnt in ethnic riots, Shah was replaced by Sindh Chief Minister Aftab Shahban Mirani. The gentle, heavy-set

Mirani with salt and pepper hair visited the bereaved Bhutto household in Shikarpur to offer prayers for the murder victim. He came from the same town as Javed’s family, but Mirani was mostly compelled to visit them because of the national attention the case had received. State television drew mileage from the visit and cameras trailed him as he personally condoled with Fauzia’s grief-stricken family.

What national television did not show was that the victim’s brother, Javed told the chief minister that he knew that influential members of the PPP government were “hiding the murderer.”

Fauzia’s murder exploded a bombshell into society and revealed wide-ranging strata of opinions. Tongues wagged as soon as the accused was identified. Fauzia’s family thought that she had most likely pressured the already married Jamali to legalize his relationship and marry her. Apparently enraged by her persistence, they speculated, he pulled the trigger on her.

I saw that Fauzia’s murder was likely to have a negative effect on middle-class parents. Pakistan is a segregated society where marriages are mostly arranged; this incident would not help. More than once, I heard parents express disapproval how the girl had had a relationship with a man to whom she was not married.

Non-governmental organizations saw the murder as closely linked to women’s low status in society. They used it to agitate for reform. The Women’s Action Forum, comprising urban, young, professional women, took on the issue as symbolic of the rights of working women. WAF was joined by another newly-created group – War Against Rape (WAR) – that mobilized men and women of all ethnic groups on the case.

Overall, working women looked to the woman prime minister to improve their situation. Benazir Bhutto had come to power pledging “to take a firm stand against the ill-treatment and exploitation of women.” Now, delegations of human rights

activists met the woman prime minister to demand that her MPA be arrested and unseated from office.

But the PPP did not unseat their member, saying they would not do so until the court reached a verdict. It was an ingenious argument – murder cases dragged on for decades without a resolution.

Every evening, the press material on the Fauzia Bhutto murder case landed with a thud on my desk. Women and human rights groups were growing frustrated at the government’s inability to catch Jamali. It weighed on me as well. With a government official accused of murder and protected by those authorized to prosecute him, there appeared to be no recourse to the law.

Within two weeks of finding the body, the chief investigator in the Fauzia Bhutto murder case, Deputy Superintendent Police Sattar Shaikh had built a solid case against Jamali. I heard the smile in his voice when he told me that no sooner did he give a piece of information to the victim’s brother, Javed, than it appeared in the next morning’s newspaper.

Javed had finally come to trust me with sensitive information. Come late evening and I would get a phone call from him, updating me on the latest find by the investigating authorities.

Call it destiny or chance: I had begun walking on the same path as the victim’s brother. In the process, I gained respect for Javed, the man who sought justice, not revenge. His decision to bring the accused before a court of law seemed especially remarkable in a society crumbling under anarchy. I was struck by his handsome presence – gentle, polite and well-spoken.

And yet, we were a study in contrasts. In comparison to his laid-back introspective style, I was restless for action. As we began our separate investigations into the young woman’s murder, he came to know me as an aggressive reporter who barraged him with questions in order to meet a newspaper’s deadline.

At an early stage of the murder investigation, Javed had come to speak with a reporter in the adjoining newspaper office

to convince him to do an investigative piece on Fauzia. I called him a couple of times on that telephone extension but despite assenting politeness, he failed to come around to my office to talk to me.

So, I walked into the other paper ’s office and asked the questions in person. I found him reticent to speak. He knew that I worked for a daily newspaper and he knew me too little to divulge the latest information. Without being rude, he had tried to brush me aside. Clearly, this was a man who did not trust easily.

We were both fired up for the same mission but remained complete strangers. I knew though that if we did not move quickly on Fauzia’s case, her murderer would vanish and she would be among the thousands of nameless, faceless victims of crime.

I decided to undertake my own investigation into the murder case. The opportunity came when my newspaper sent me to report on another issue in Nawabshah. It provided me the perfect opportunity to call upon Jamali’s driver, Mohammed Ishaq – who, after being released on bail, had returned to his village near Nawabshah city.

Once I had located his address, I took the office van to the driver ’s mud dwelling. The driver went inside and called Ishaq. A few minutes later Ishaq emerged nervous and disheveled. He was aware that the fact that I had traveled from Karachi meant that I was on important business.

The two of us sat upright, opposite one another in the spacious van and Ishaq narrated the story of that fateful night. He spoke in a resigned tone, in Sindhi-accented Urdu. It was the same account he had given to the police.

“Yes, he killed her,” he told me nervously. His matter-of-fact tone made me angry. Ishaq had driven off with Jamali to Nawabshah after the murder and would never have confessed had the police not arrested him. Knowing that I was staring at him, Ishaq dared not look up. Instead, eyes down, he muttered, “What could I do? He threatened to kill me if I told anyone.”

Fear had crippled this poor man of peasant origin. For the lowly driver to have testified against his master – a wealthy landowner, well-connected lawyer and an MPA – would have meant devastation for his entire family.

Although Sindhi feudal landlords are represented in the country’s two major political parties, they have kept their peasants ignorant and fearful. As a cynical Urdu-speaking friend of mine was fond of saying, “When one landlord wants to take revenge against another, he opens a school in the other’s locality”.

To Ishaq, I was a powerful figure from the city that belonged to the same social class as the landlords. When he described the entire murder scene, he never once looked up. Not just because I was a woman – people of lower status are not supposed to look into the eyes of the higher class.

As I left, I knew that although he had confessed to me privately and testified in front of a magistrate, he would never have the courage to testify against his master in a court of law.

The city was abuzz with news about Fauzia’s murder. In the forefront were women activists, resolute on building pressure to catch the murderer. I attended their meeting at the Karachi Press Club where Javed was also present. His face was alive with expectation. He had come to depend on civil society to bring his sister’s killer to justice.

We discussed the possibility of my smuggling a group of women inside the Sindh Assembly building – banners and placards in tow – to demonstrate inside the premises and demand that the run-away Jamali be brought back to face murder charges. It was a novel idea proposed by WAF and WAR and I shared the excitement of what this could do to publicize the case.

The next morning, the handful of women activists piled in my car and we drove to the imposing Sindh Assembly. We planned that the bulk of protestors would unfurl their banners outside, once our “inside group” got in. They would then join a much larger group of activists on the street outside the parliament building.

As I drove to the majestic assembly gates, the guards peered in. They took one look at my assembly pass and then waved us in…just a harmless group of women. I parked inside the

prepossessing Sindh Assembly building – its grandeur masking the unruly sessions between government and opposition. My women friends waited in the assembly’s cafeteria room and I went to the opera house style press gallery.

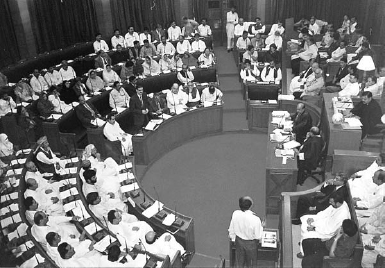

Figure 8

PPP parliamentary leader Nisar Ahmed Khuhro addresses Sindh Assembly (

Dawn

photo).

The press gallery affords a bird’s eye view of the legislators under a large canopy of the British built parliament building. From here, I frequently watched the vitriolic exchanges between the government and opposition members.

Over a month had passed since Jamali had fled. I looked down to his seat to see if the assembly session had coaxed him back to his seat. Not surprisingly, his seat was empty.

As the session ended, the unsuspecting legislators walked out of the front door, smack into the middle of the women’s demonstration. The women had lined up for the protest in their modest

shalwar kameez

in vibrant spring colors, with

dupattas

strung across their necks. They dramatically unfurled banners and placards with slogans that read “Arrest PPP MPA Rahim Baksh

Jamali” and “Arrest Jamali – Fauzia Bhutto’s murderer.” Female voices rent the air: “Arrest the killer of Fauzia Bhutto.”

Traditionally, the Sindh Assembly is a male enclave of feudal and urban parliamentarians, reporters and security personnel. But that day the legislators were taken aback by the sudden appearance of upper-middle class women demonstrating for women’s rights.

I saw the discomfort on the faces of the PPP legislators as they tried to avoid the demonstrators and instead walked briskly, mobile phones in hand, toward their Pajeros, the huge vehicles that symbolize feudal prosperity.

But before the parliamentarians could escape, the journalists who normally cover the Sindh Assembly went into action. As reporters took notes, newspaper’s photographers bent out of shape to snap legislators fleeing the bad publicity. It was not that easy for the PPP parliamentarians to escape. Outside the Sindh Assembly building there was a larger demonstration of women with banners and placards, demanding Jamali’s arrest.

Our inner group came out of the assembly gates and joined these daughters, sisters and wives of the crème de la crème. The assembly reporters had their work cut out for them. Even while many members of parliament had already revved up their high-powered vehicles and fled, the story of their runaway colleague would follow them the next day.

That night as I drove home after work, I knew the satisfaction of a day well spent. And yet, as I drove through the dark, silent streets of Karachi, I felt as though I was being followed. It was a familiar feeling. Years of driving home alone at night had taught me to shake off pursuers.

But that night something was different. I had glimpsed a man in my car mirror, who trailed me in a pick-up truck. Trying to shake off the eerie feeling, I looked behind and saw the street was empty. Gathering courage, I disembarked to open the gates of my house. Cautiously, I drove in and closed the gates behind me. This was my daily ritual.

Just as I walked up the three short steps to my house, I sensed a figure had crept up from behind. Instinctively, I called out, “Ma.”

It was just as well. At that moment, a hefty man had jumped over the boundary wall and pulled my tunic from behind. My karate reflexes came into play – I wrenched free and hit him with my bag.

In that split second, my mother had opened the door and the assailant vanished. My mother told me it had been the note of urgency in my voice that had made her run to open the door. My father turned on the balcony light and ran out into the courtyard to see if he could spot anyone. But the attacker had vanished.

Three weeks after Jamali’s disappearance, as I dropped off a routine news report for my city editor Akhtar Payami, he quietly drew my attention to a news item from the wire services.