Aboard the Democracy Train (26 page)

Read Aboard the Democracy Train Online

Authors: Nafisa Hoodbhoy

When the Taliban began suicide attacks to avenge military action, parliamentary opposition leader, Maulana Fazlur Rehman denied there were suicide bombers in Pakistan. Instead he referred to the blame on Islamic extremists as “a Western conspiracy to malign Pakistan.”

In 2006, as the Bush administration claimed the elimination of Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi in Iraq as a great victory, the

JUI (F) tried to offer prayers for him in the National Assembly. One of their top Islamic leaders, when questioned about the move to offer prayers for Zarqawi, who was deemed to be a terrorist, responded, “A terrorist for some is a freedom fighter for others.”

Figure 9

JUI (F) Chief Maulana Fazulur-Rehman addresses rally in Sukkur, Sindh on September 26, 2004 (

Dawn

photo).

The Musharraf government entrusted the JUI (F) leadership to persuade tribal leaders in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) to hand over foreign militants who had re-converged after their exodus from Afghanistan. The Taliban saw little need to make concessions in

jirgas

(tribal meetings), led by sympathetic Islamic party leaders. Instead, their militants closed off FATA to outside forces and implemented harsh Sharia laws to govern the local tribesmen.

As the Taliban leadership grew in the FATA areas, the JUI (F) leaders praised them even louder. They had a reverential attitude toward Baitullah Mehsud, who first fought against the Soviets and later became a protégé of Afghan Taliban leader, Mullah Omar. In the words of a tribal leader from the JUI (F), “Baitullah Mehsud

is a commander who has a huge following not only in Waziristan but in the entire tribal area.”

Figure 10

Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan Chief Baitullah Mehsud in Sararogha, South Waziristan on February 7, 2005, shortly before he signed the peace deal with the Musharraf administration (

Dawn

photo).

Although the Pakistan military kept up its offensive against the Taliban militants, the MMA Islamic coalition argued in favor of peace deals. Whenever their

jirgas

failed to keep the peace, the Bush administration demanded that the Pakistan military launch an offensive against the militants. The military offensives were followed up by fresh peace deals, which, like the ones signed with the Taliban in South Waziristan in 2004 and 2005, only allowed the Taliban militants to grow stronger.

As the armed militants from the Pashtun tribe operated between the seamless hills on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, President Gen. Pervaiz Musharraf and President Hamid Karzai hurled accusations and counter accusations at each other as to

who

was responsible for the resurgence of the Taliban. The army spokesman, Maj. Gen. Shaukat Sultan admitted that while militants came from Afghanistan to engage in subversive

activities inside Pakistan, they also ran across the 1,200-mile border to create trouble for the Afghan government.

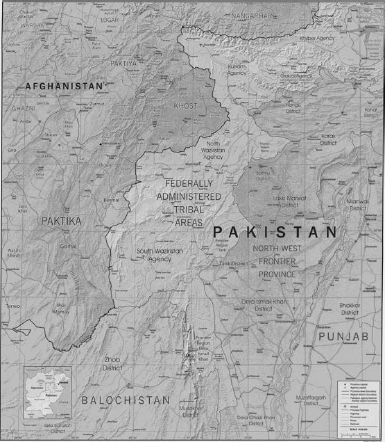

Map 2

Map of FATA.

Source: University of Texas.

The Pushtun ethnicity of the Taliban – who straddle the seamless Pak-Afghan border – and their common objective of fighting US occupation forces in Afghanistan helped the leaders of both nations – Musharraf and Karzai – to avoid taking direct responsibility for the resurgence of Islamic militancy in the region.

With stepped-up US and NATO patrols in Afghanistan, the Taliban and Al Qaeda found Pakistan’s tribal Waziristan belt a much more hospitable terrain to resettle and reorganize. The Al Qaeda’s militants, who were welcomed by the US to fight against the Soviets during the Cold War, had already integrated through marriages within the local tribes. In the post-9/11 era, the peace deals offered by Musharraf allowed them to recreate a Taliban state that mirrored their fallen government in Afghanistan.

Over time, the Taliban murdered hundreds of

maliks

(tribal landlords) in FATA, accused of spying for Pakistan; beheaded drug peddlers, kidnappers, looters and dacoits and collected

jaziya

(taxes on non-Muslims) to establish their rule. It would change the traditional social structure and hierarchy and cause an exodus of landlords

,

political agents and secular communities to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s settled areas.

In Khyber Agency, the main artery connecting Peshawar to Kabul, a running battle between two religious groups – led by Mufti Munir Shakir and an Afghan, Pir Saifur Rehman – in 2005 resulted in a heavy loss of life. Shakir’s group spawned the Lashkar-i-Islam (Army of Islam), whose leader Mangal Bagh used FM radio stations in the

madressahs

(Islamic schools) of the tribal belt to incite listeners into acts of sectarian violence against the local Shia population. From time to time, they blew up transmission towers of FM radio stations to stop the government from broadcasting music and information.

While the government encouraged the predominantly Shia population of the surrounding Kurram agencies to form tribal armies – or

lashkars

– for self-protection, the militants responded by suicide missions that included ramming explosive laden vehicles into

jirgas

(tribal councils). These militants banded under the ASSP and LEJ also found ways to attack Shia refugees and their congregations in prayer houses, shrines and mourning processions that stretched all the way from Khyber to Karachi.

Although Shias did not turn against Sunnis on a large scale, as has been the case in Iraq, these attacks led to steady

stream of retaliation. Where the military took on the Taliban, their sectarian affiliates responded with growing attacks on non-Muslims, surpassing the sectarian violence witnessed two decades before.

As the Bush administration mounted pressure on Pakistan to “do more” in the “War on Terror,” Pakistan’s army soldiers came in the front line of fire. Being poorly equipped and trained, the conventional army was no match for the well-armed Taliban who fought with guerrilla tactics that included improvised explosive devices (IEDs), suicide attacks, kidnappings and beheadings. It led to situations in which entire contingents of soldiers were kidnapped and several were beheaded. Others were either forced to surrender or voluntarily deserted the army.

In 2006, matters reached a point where Musharraf was forced to make a deal with Taliban militant Hafiz Gul Bahadur in North Waziristan that his tribesmen would expel foreign fighters from the tribal belt and refrain from attacking the Pakistan military in return for the administration’s movement of 80,000 troops from check posts in Waziristan to the Afghan border. The deal succeeded in getting rid of Uzbek fighters – subsequently leading to the assassination of their chief, Tahir Yuldashev, through a drone attack.

But the North Waziristan deal would eventually turn the area into the last refuge for jihadists. As late as 2010, Awami National Party Senator, Afrasiab Khattak admitted to me that Gul Bahadur ’s forces had become a “problem” for his government.

Meanwhile, tribesmen were eyewitnesses to the return of Afghan Mujahideen commander Jalaluddin Haqqani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar in North Waziristan. In December 2009, these former CIA-funded Mujahideen gave sanctuary to a Jordanian double agent who used suicide bombing to wipe out a sizeable portion of US intelligence officials who were posted at Khost, Afghanistan.

Former FATA security chief Brig Mahmood Shah, who quit his post in 2005, calls the North Waziristan accord “a bad deal” that enabled the Taliban to consolidate its position. While initially the Afghan Taliban did expel foreign fighters from the region, soon it

was back to square one as the Haqqani network attracted foreign jihadists and launched increasingly daring attacks against NATO forces in Afghanistan.

During Musharraf, the Bush administration worked out a deal with him to allow drones to take out “high value targets” in the FATA areas bordering Afghanistan. Both sides kept a high level of secrecy about the drone attacks and for years the Pentagon refused to acknowledge them. Musharraf’s media spokesmen were given the difficult task of answering to civilian deaths in drone attacks, even while his administration scuttled the issue.

The US gradually increased drone attacks in FATA to counter growing insurgent attacks on NATO troops in Afghanistan. By 2007 drone attacks were frequently used against the Tehrik-i-Taliban (TTP), which surfaced under the leadership of Baitullah Mehsud and was found responsible for a substantive increase in the Afghan insurgency. That year, as Pakistan buckled under US pressure and killed Taliban militants in South Waziristan, Baitullah’s response was to launch a spate of suicide attacks against military and police targets in Pakistan.

Still, careful not to antagonize Baitullah, the Musharraf administration sent delegations led by JUI (F) Senator Saleh Shah and the late Maulana Merajuddin to negotiate with the TTP militants. These leaders were ever-ready to defend the fire-brand militant. They held Baitullah Mehsud in awe, notwithstanding the fact that the militant had let fall all pretenses and declared open war against Pakistan.

On the other hand, the Afghan Taliban led by Afghanistan’s deposed Taliban leader,

Amir ul Momineen

(Leader of the Pious), Mullah Omar, assiduously avoided attacks on Pakistan and instead used its territory to launch attacks against NATO troops in Afghanistan.

As the CIA became more vocal about the ISI’s role in shielding the Afghan Taliban, the US threatened to take drone attacks deeper

into Pakistan’s territory. Talk of an Afghan government in exile – notably the Quetta Shura – gained currency as the US alleged that Mullah Omar and his coterie had formed a government-in-exile in Balochistan. Even if the US threatened to carry out drone attacks in Quetta, merely to test the waters, anxious residents expected the missiles to rain on them any day.

In Quetta, it is an open secret that Mullah Omar’s fighters often travel to neighboring Qandahar in dark-tinted vehicles, laden with weapons. From time to time, they ambush the NATO supply trucks at Chaman, bordering Qandahar. Those wounded by NATO troops are brought back by popular routes for treatment to Quetta’s hospitals. Still, the Afghan Taliban refrain from attacking targets inside their host country and instead keep a good relationship with the Pakistan army, which in turn looks the other way for its broader strategic objectives.

On the outskirts of Quetta lies a well-lit colony for the Afghan Taliban called Kharotabad. This base camp in the hills sparkles amid otherwise dark surroundings. Apart from Pashtuns, the three other ethnicities of Afghanistan – the Uzbek, Tajik and Hazara – are frequent visitors. The colony has become a notorious focal point for the smuggling of heavy weapons, narcotics, as well as vehicles and tunnels that enable a quick getaway.

But even as the US-leaked memos and statements accused the ISI of secretly supporting the Afghan Taliban, Pakistan put its foot down on allowing the US to operate inside settled areas. While US drone missile strikes grew more frequent, they were only allowed to operate in the FATA belt along Afghanistan. Drones became a weapon of choice in North Waziristan, where Al Qaeda’s foreign fighters and Taliban congregated but where the military held off from conducting any operation.