Adrift (16 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

Doing just enough to hang on will no longer do. I must keep myself in the best shape possible. I must eat more. I pull in the string farm trailing astern and rake off the barnacles with the blade of my knife. I scrape some rust from the peanut and coffee cans into my drinking water in the hope of absorbing some iron and alleviating anemia.

I talk to the lazy vagrant in control of my body. I coax him to kneel by the entrance to await another dorado. At first my body is slow. A dorado swims out. I clumsily splash down. Miss. Another. Miss. But the pumping of blood helps to revive my other self, the physical part. On the third shot I ram my weapon through the fish's back. It pulls me down over the tube as it twists and jerks to get away. I play the fish as if he's on a light line, because I don't want to break or bend my lance. However, I must also retrieve it as quickly as possible, before it can escape. So I let it twist and jerk while I reach down and grab the shaft close to the body; then I lift it up without the risk of bending the shaft. I flip the fish inside, onto the sailcloth blanket that protects the floor. When I get the dorado pinned down with my knees, I slip the cutting board under its head just behind the gills, push my knife into the lateral line, and break the spine with a quick twist of the blade. Usually I completely clean the fish before eating, but now I'm very hungry. I simply gut it and place the rest aside.

By midafternoon I am eating the organs, and I feel as if I have had a transfusion. The dorado's stomach seems full of something. I cut it open. Five partially digested flying fish spill out onto the floor. I hesitate, take a small taste of a flyer, and almost vomit. I gather them up and toss them out. As soon as they are in the air I think, Fool! You should have washed them off and then tried them. Next time. But such a waste of five fish. I mop up the spilled stomach juices and finish cleaning the dorado. Sweat pours off of my head as I squat over my catch and labor in the heat to slice up the body. I stop twice to stretch out my legs and to relieve my cramped knees and back. The work is hard, but I move fast so that I can rest sooner. I always work that wayâpushing myself as hard as I can so I can finish quickly and then find complete rest.

As I poke holes through the fish sticks in order to string them up, SLAM!

Rubber Ducky

crushes me between her tubes. Water dribbles in and she springs back to her normal shape as though nothing has happened. It takes me a moment to get my wind back and recover from the shock. The average wave height is only about three feet, but a monster leisurely rolls off ahead. I set to work again with a shrug. I am getting used to various levels of disaster striking with no warning.

The still lies lifeless, draped flat over the bow. It must have gotten smacked pretty hard. Air jets out of it almost as quickly as I can blow it in. The cloth across the bottom, which allows excess seawater to drain through and which is airtight when wet, now sports a hole. The cloth has deteriorated from the constant cycles of wetting and drying and from chafing against

Ducky's

tubes. Less than thirty days of use, and the still is gonzo. I've never been able to coerce my remaining still to work. As we have drifted west, the number of light showers has increased, but I am lucky when I can trap six or eight ounces of water within a week. Another critical safety margin has disappeared. I'm in big troubleânot that I've been out of big trouble for quite a while now.

I must get the other still to work and keep it working, perhaps for longer than thirty days. I blow it up until it's tight as a tick. Just below the skirt through which the lanyard passes, a tiny mouth whistles a single-note tune until the balloon's lungs are emptied. The hole is in a tight corner and on a lumpy seam, which makes it impossible to effectively wedge a piece of repair tape into it. Making something watertight is difficult enough, even for a boat builder in an equipped shop. To make something airtight is an even taller order.

For hours I try to think of a way to seal the leaking still. Perhaps I can burn some pieces of plastic from the old still or its packaging and drip the melted globs over the hole. But I find that my matches are sodden and my lighter has been drained of fluid. So I wedge the tape in as firmly as I can and grouchily reinflate the still every half hour. Each time, the still begins to slump as soon as I stop pumping. Water begins to collect in the distillate bag, but it is salty. At this pace, I already feel like I have a case of lockjaw, and my mouth is very dry. I must find an effective solution. If only I had some silicone seal or other kind of good goop.

MARCH

16

DAY

40

I have managed to last forty days, but my water stock is declining, and I have but a few hard pieces of fish dangling in the butcher shop. It is also a little disconcerting to realize that

Ducky

is guaranteed for forty days of use. If she fails me now, do you suppose I

can

get my money back?

Despite these problems, I have good reason to celebrate this milestone. I've lasted longer than I had dreamed possible in the beginning. I'm over halfway to the Caribbean. Each day, each hardship, each moment of suffering, has brought me another small step closer to salvation. The probability of rescue, as well as gear failure, continually increases. I imagine two stone-faced poker players throwing chips onto a pile. One player is named Rescue and the other is Death. The stakes keep getting bigger and bigger. The pile of chips now stands as tall as a man and as big around as a raft. Somebody is going to win soon.

The dorados begin their morning foray. They bang away at the bottom of the raft and sometimes run around the outside, cracking stiff shots against the raft with their tails. I grab my spear and wait. Sometimes I have a little trouble focusing. During the last gale I jabbed my eye with a piece of the polypropylene line I've rigged to keep the still in place. After a couple of days of oozing and swelling, my eye cleared up, but I was left with a spot in my vision, which I often take to be a glimpse of an airplane or the first hint of a fish shooting out before the tip of my spear. Dorados are so fast that my shot must be instantaneous, without thought, like a bolt of lightning. A head, a microsecond of hesitation, a splash, a strike, a hard pull on my arm, and an escape. On other days I've hit two or three morning and evening but most of the time come up with nothing. This morning I'm lucky and catch a nice fat female. Squatting over her for two hours on the rolling floor of the raft is hard work for my matchstick legs. Finally the job is done and the fish hung up to dry. I begin to mop up the blood and scales, but my sponges have turned to useless little globs. Evidently the stomach juices that I swabbed up from the last dorado have digested them. Since my sleeping bag has proven its ability to soak up water, I take out some of the batting and bind this up with pieces of codline to use as sponges.

Each day now I set my priorities, based on my continuing analysis of raft condition, body condition, food, and water. Each day at least one factor lags behind what I consider adequate. The dismal problem of collecting or distilling water is one I must find a solution to.

I take some of the black cloth wick from the first still, the one that I cut up early in the game. I affix it across the hole of the still with the rotted bottom, letting the still's weight keep it in place. I now have one still aft and one forward, in the only positions available for frequent tending. Every ten minutes throughout the day, I am a human bellows at the service of one or the other still. In between inflations, I empty the distillate just in case salt water sneaks in to pollute it while I'm not watching. By nightfall I have collected a full two pints of fresh water. I am continually paying higher prices for my small successes. The work is demanding and boils off a lot of body fluid. I can't decide if my steaming cells gain anything from the exercise. There is little time to dream these days, barely enough time to live, but fruit mountains still stand in the panorama of my mind's eye.

The next day my debate over the value of operating both stills becomes moot. The entire cloth bottom on the older still gives way. Throughout the day I keep the one still working and try to devise a patch for the old. I painstakingly poke holes around the rim of the opening, using my awl, then thread through sail twine and sew on a new cloth bottom. I try to seal it with the bits of tape that I have left, but the patch remains an utter failure. The still lies dead no matter how hard and fast I try to resuscitate it.

Luckily I'm learning about the personality of the new still. The inside black cloth wick is wetted by seawater dripping through a valve on the top of the still. The rate at which the inside wick is wetted is critical to production of fresh water. If it's too wet, it doesn't heat up efficiently. Instead, the excess, warm seawater just passes out through the bottom cloth. If the wick is too dry, there is less than the maximum amount of water available for evaporation. I must maximize the rates at which the water will evaporate, collect on the inside of the plastic balloon, condense, and finally drop into the distillate collection bag. It seems that the inside pressure of the still affects the rate of dripping through the valve. The still seems most efficient at a pressure that allows it to sag, but not so much that the wick hits the plastic balloon, because if that happens the salt water in the wick is drawn into the distillate. To keep her at just the right inflation requires constant attention.

To help prevent another failure of the bottom cloth, I make a diaper for the still out of a square of sailcloth and add padding, using the cloth wicking from the cut-up still. I blanket the bottom of the still by tying the diaper up by its corners to the lanyard skirt, hoping the diaper will take the chafe from

Ducky

and will keep the bottom cloth constantly wet to delay rotting.

My rain collection systems also need improvement. At the first

thrrrap

of water droplets from the sky, I usually wedge the Tupperware box against the aft side of the still. It's held in place by the still bridle. The arrangement is simple and is quick to rig or empty, which is important in order to minimize salt water pollution from breaking waves and spray. However, I think that I can catch more water if I can find a way to mount the Tupperware box on top of the raft. I need to put a bridle around the box so that I have something to secure it with. The awl on my jackknife has a cutting edge, so I wind it into the plastic lip that runs around the box, boring a hole in each corner. Through these I string a collar made of sail twine. I secure the two ends of one bridle to

Ducky's

tail, lead the middle of it to the top of the arch tube, and equip it with a quick-release metal clip that I've stolen from one of the stills. Forward, I tie a short lanyard to the canopy entrance and affix a second clip to the other end, which I also lead to the peak of the canopy. When I have to use the Tupperware for some other purpose, I leave the two clips hooked together, so that they are always ready. As soon as it begins to rain, I can quickly flip the clips onto the collar of the box, which keeps it pretty secure on the apex of the arch tube, angled more directly into the wind and higher away from the waves. Its biggest benefit is that it is no longer blanketed from rainfall by the canopy, which is now below it. In fact, it will prove twice as effective this way.

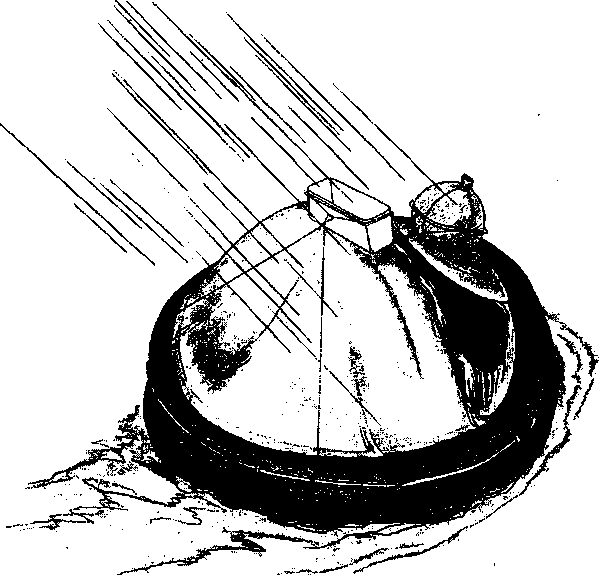

The Tupperware box is twice as effective as a rain collector when I rig it up on top of the raft. The bridle that secures it to Ducky's stern can be quickly released. It is clipped to the box's string collar. A matching clip and bridle faces forward, out of view. The box may then be used for other purposes between rainfalls by removing it and clipping the two hooks together.

Finally I must tend to my steel knives. My Cub Scout jack-knife with the awl is one that I found when I was twelve. The spring on its main blade has always been broken, so the blade flops about a little. It's a ball of rust now. I scrape it clean. I sharpen both it and my sheath knife frequently. Rubbing the steel hard against fish skin that has a tissue of fat attached produces a tiny drool of fat, which greases the blades until they shine. I treasure raw materials and basic tools; so much can be done with them. Paper, rope, and knives have always been my favorite human inventions. And now, all three are essential to my own sanity and survival.

MARCH 18

DAY

42

Each day seems longer. On my forty-second in the raft, the sea is as flat and hot as an equatorial tin roof in August. The sun in the sky is joined by hundreds that flash from water ripples. It is all I can do to try to move about in

Ducky.

We sit like a period in a book of blank pages.

I find that my sleeping bag helps to keep me cool as well as warm. I spread it out over the floor to dry in the sun. When I stick my legs under it, they are shaded and sandwiched between the wet bag and the cool, damp floor. It is not very good for my sores, but they are not too bad now and the relief from the heat is quite noticeable. Without the bag covering, the black floor becomes very hot and the whole inside of

Ducky,

which is hot enough as is, becomes an unbearable oven.