Adrift (25 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

I measure my latitude with my sextant. About eighteen degrees. How accurate is it? I know now I will never last another twenty days. If I am too far north, I am done for. If I could manage the wind, I would make it take me south.

APRIL 10

DAY

65

In the morning the dorados are gone. Several of a new type of triggerfish appear. They are almost black, with bright blue spots, puckered mouths, and fins like chiffon collars rolling in a breeze. They look to me like oceanic starlets. I call them my little coquettes.

Two long fish torpedo under the raft. They are even faster than the old blue dorados, though they must be a type of dorado. They're smaller than the blue doradosâtwo and a half to three feetâand their skin is a mottled green and brown, like army camouflage. One of them looks badly damaged: raw, pink skin shows where most of the camouflage has fallen away in large sheaths. I think of it as having ichthyofaunic mange.

Tiny black fish, maybe an inch or two long, sweep along before the raft, contrasting sharply with the Atlantic's topaz blue. Their bodies wiggle as if made of soft rubber.

Ducky's

slow forward progress creates small ripples, what could jokingly be called a bow wave. Just as porpoises ride the pressure waves that are created by a ship's bow rushing through the sea, so these tiny black fish swab little arcs just ahead of

Ducky's

backwash. I try to scoop them up with my coffee can, but they are always too fast.

Since the long battle to repair

Ducky's

bottom tube, I've been pretty wiped out, but I feel a little stronger this evening. For the first time in over a week, I return to my yoga routine, first spreading out my cushion and sleeping bag to cushion the dorados' blows. The hemorrhoids are purred out again, and my hollow butt provides little protection. I sit up, bend one scrawny leg until my heel rests firmly in my crotch, and then touch my head to the knee of my straightened leg, while grasping the foot of that leg with both hands. I perfect a twisting exercise while hanging on to the handline. Then I lie on my stomach and lift my head as if doing a pushup, but I keep my legs and hips on the floor and bend my spine back into a wheel. I scoot forward, lie on my back, raise my legs over my head, and bring them around until my feet hit the floor behind me. My body weaves about like a stock of kelp swaying in the currents. I have not only sea legs but sea arms and a sea back, perhaps even a sea brain.

My head is struck hard. I wiggle my jaw to see if it is loose. The new camouflaged dorados are very powerful and aggressive. They bombard the raft all day long, ramming it with their bullet heads, slapping at it with their bullwhip tails, and blasting off with incredible speed. I leap to the entrance and grab the spear, but they are always long gone. Sometimes I glimpse their tails as they shoot off into the distance. Sometimes I see them racing by, several fathoms below. They never move calmly like the big blue dorados. They always move frantically, like they're hopped up on speed.

As the sun sets, I hear squeaking again and spy some big black porpoises, purposefully cutting their way to the west. They do not come close, but I feel touched by the graceful ease with which they glide through the Atlantic's swell.

The frigate birds, three of them now, are still frozen in position, riding the invisible waves of the sky high above the water. I'm impressed that their delicate long wings survive the power of the sea. They are often above me at first light, or they drift up from the west soon after. Another snowy tern shows up; it is unbelievable that this tiny bird migrates eleven thousand miles every year.

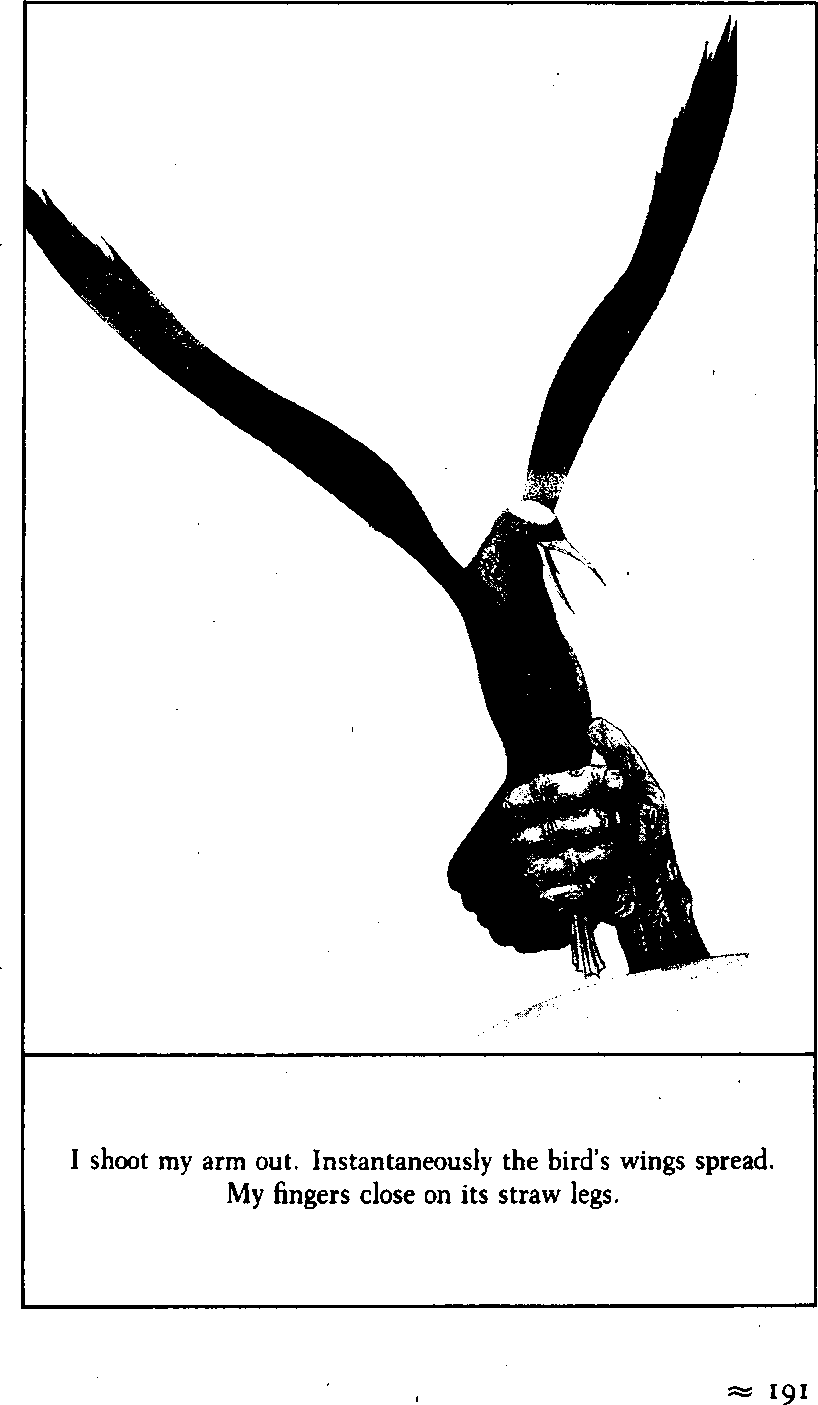

A dark gray bird swings back and forth, approaching from where the clouds go, slowly getting closer. It flies like a crow. I tell myself that it must come from land. More important, it is a flying lump of food. It nears. I duck behind the canopy. I can't see it, but I hear it fluttering at the entrance to my cave, contemplating entry. It flaps away. I wait. A shadow flickers on the canopy, grows, and a slight weight puts an imprint on the tent peak. Cautiously I bend forward and see the bird perched, looking aft, its feathers rustling in the wind and then falling back into place. I shoot out my arm. Instantaneously the bird's wings spread. My fingers close on its straw legs. It squawks and snaps its wings down to gain lift, wheels its head around, and madly pecks at my fist. I grab its back with my other hand, drag its claws free of the tent, pull it into my den. In one quick move I twist its head around. There is a silent snap.

The beautiful plumage is so pristine and well tended that I feel like a criminal disturbing it. I don't know what kind of bird this is. It has webbed feet, a long thin beak, and pointed wings spanning about two and a half feet. It is a sooty color all over, except for a round light gray cap on the top of its head. The skin is very tough and the feathers are stuck well into it. Robertson suggests that it's easier to skin a bird than pluck it, so I cut off the wings and head with my sheath knife and peel off the skin. The breast makes up most of what is edible, and that's not much of a meal. The meat is of a different texture than fish, but it tastes almost the same. Once they are dissected into organs, bones, and muscle, it is surprising how similar to one another are the fish of the sea, birds of the sky, and, I suppose, mammals of the land. Five silvery sardines are in its stomach. Caught near land? There's little to the wings except bones and feathers. They're quite beautiful. I don't want to throw them out, so I hang them from the middle of the arch tube.

By evening the bigger blue dorados return en masse, still lorded over by the emerald elders. Escorting us into our sixty-fifth night is an assemblage of about fifty. Every now and then one of the brown and green camouflaged dorados strikes like the blow from a sledgehammer, unleashing a squirt of adrenalin in me as I momentarily mistake the blow for a shark attack. I call the smaller brown and green dorados tigers. As if inspired by the tigers, one of the biggest male blue dorados frequently flips along the perimeter of the raft, giving it great whacks, smashing the water into foam, and pushing

Ducky

this way and that. I ignore it. In the morning I get my easiest catch yet. Within ten minutes and using only two shots, I have a fine female hauled aboard.

By nightfall the waves have reared up again and ricochet off of

Ducky's

stern. Each wave that breaks on the raft echoes through the tubes and sounds like a blast from a shotgun going off next to my ear. The wind catches the water catchment cape, snaps it up and down, rips its buttonholes wider, and tries to tear it away. During the night conditions become wilder. Watery fists knock

Ducky

back and forth. I huddle athwartships, getting as far forward as I dare in an effort to stay dry while also trying to keep the stern down. Although the front of the canopy gives a little better protection, dryness is still relative. The back of the canopy is little more than a stretched rag. Wave crests fall on it and drain through onto my face, stinging my eyes and pouring into my sleeping bag. I continually wipe the water off the floor and the canopy, but everything is soaked in no time.

APRIL

12

DAY

67

It is April 12, the date that marked the anniversary of my marriage such a very long time ago. Frisha's life as my wife was not easy. I'd take off on a delivery trip or a passage and leave her behind. Sometimes we wouldn't see each other for months. She thought that it was all a very risky business, despite my reassurances. Not long before I left the States on

Solo,

she told me that she thought I would eventually meet my maker at sea, but that it would not be during this voyage. I wonder how she feels about it now. I wonder if she was right. What is Frisha doing? She must believe that I am dead while she studies to bring life from the soil. One day, perhaps, long after I am drowned and consumed by fish, a fisherman may haul aboard a catch that will find its way to her table. She will take the head, tail, and bones and heap them upon her compost pile, mix them with the soil so green life will sprout. Nature knows no waste.

A flying fish crashes onto the canopy behind the solar still. I am losing my taste for fish, but any change from dorado arouses my appetite. My guts feel like they have fallen right out of me. No amount of fish can fill my vacant stomach. I sit up, grab the flyer, and wonder if it is scared or if it accepts death like another swimming stroke.

Maintaining discipline becomes more difficult each day. My fearsome and fearful crew mutter mutinous misgivings within the fo'c's'le of my head. Their spokesman yells at me.

"Water, Captain! We need more water. Would you have us die here, so close to port? What is a pint or two? We'll soon be in port. We can surely spare a pintâ"

"Shut up!" I order. "We don't know how close we are. Might have to last to the Bahamas. Now, get back to work."

"But, Captainâ"

"You heard me. You've got to stay on ration."

They gather together, mumbling among themselves, greedily eyeing the bags of water dangling from

Ducky's

bulwarks. We are shabby, almost done for. Legs already collapsed. Torso barely holds head up. Empty as a tin drum. Only arms have any strength left. It is indeed pitiful. Perhaps the loss of a pint would not hurt. No, I must maintain order. "Back to work," I say. "You can make it."

Yet I feel swayed more and more by my body's demands, feel stretched so tight between my body, mind, and spirit that I might snap at any moment. The solar still has another hole in it, and the distillate is more often polluted with salt water. I can detect less and less often when it is reasonably unsalty. I may go mad at any time. Mutiny will mean the end. I know I am close to land. I must be. I must convince us all.

We've been over the continental shelf for four days. One of my small charts shows the shelf about 120 miles to the east of the West Indies. I should see the tall, green slopes of an island, if my sextant is correct. I should hit Antiguaâironically, my original destination. But who knows? I could be hundreds of miles off. This triangle of pencils may be a foolish bit of junk. The chart could be grossly inaccurate. I spend endless hours scanning the horizon for a cloud shape that does not move, searching the sky for a long wisp of cloud that might suggest human flight. Nothing. I feel like a watch slowly winding down, a Timex thrown out of an airplane just once too often. I've overestimated my speed, or perhaps I'm drifting diagonally across the shelf. If there was only some way to measure the current. I'm assuming that I'm within two hundred miles of my calculated position, but if I've been off by as little as five miles a day, I could be four hundred miles away from where I hope I amâanother eight or even fifteen days. "Water, Captain. Please? Water." Tick, tick, slower and slower. When will it stop? Can I wind it up until the end of the month without breaking the spring?

The next afternoon's sun is scorching. The solar still keeps passing out and looks as if it may not last much longer. By mid-bake-off I can feel myself begin to panic and shiver.

"More water, Captain. We must have more."

"No! No! Well, maybe. No! You can't have any. Not a drop."

The heat pours down. My flesh feels as if it is turning to desert sand. I cannot sit upright without having trouble focusing. Everything is foggy.

"Please, Captain. Water. Now, before it's too late."

O.K. The tainted water. You can drink as much of it as you want. But the clear water remains. One pint of it a day. That's the limit. It's the limit until we see aircraft or land. Agreed?"

I hesitate. "Yes, all right."

A sludge of orange particles sits in the bottom of the plastic tube in which the wretched canopy water rests. I triple layer my T-shirt and strain the water through it into a tin again and again. The result is a pint of cloudy liquid. It is bitter. I can just keep it down.

My thirst becomes stronger. Within an hour I must drink more. In another hour more still. Soon the bitter pint is gone. It is as if my whole body has turned to ash. I must drink even more.

"No. Can't. No more until tomorrow."

"But we must. You've poisoned us now and we must."

"Stop it!" I must keep command. But my eyes are wild, my limbs shaking in an effort to hold back the panic.

My torso screams out. "Take it!" Limbs reach out for a sack of water

"No!" I scramble to my knees, almost in tears. I get to my feet and look aft for a moment. I can't stand forever but for now the breeze cools me off.

There, in the skyâa jet! Not just a contrail or the faintest hint of a jet, but a silver-bodied bird streaking to Brazil! Quick, man, the EPIRB! Battery is probably shot. Well, the light's on at least and he can't be more than ten miles away. I'll leave it on for twelve hours. The jet looks small. It may not be a commercial flight. Regardless, it couldn't have come at a better time. We must be close. I fulfill my promise. I hand out a pint of clean, sweet water. Everybody relaxes.

A gooselike bird resembling a gannet flies over. It has even-colored brown plumage, except for dark rings around its eyes. Yesterday a jaeger winged by. It was not supposed to be there. Should I inform these birds that they are beyond their prescribed ranges? New fish, new birds, different water color, no sargasso. It all adds up. This voyage

will

end soon. I stare intensely at the horizon until my eyes water.