Adrift (23 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

Off of Puerto Rico, the ship

Stratus

sights a small boat adrift.

Stratus

reports to the Coast Guard, which asks for a description of the derelict vessel. It does not fit

Solo's

description. By day's end, the Coast Guard notifies my family that the "search" for me has ended. They do not mention the

Stratus.

My brother Ed has been calling my parents daily to see if there has been any word from me. He is frustrated by the lack of information from official sources. Either they are not telling everything they know, or they are not conducting a very extensive search. Ed leaves his home in Hawaii and boards a plane for Boston, where he joins my parents and brother Bob. They will conduct their own search-and-rescue mission.

In the dark, I cannot sleep. The wretched water sloshes about in my gut like a heavy stone. My head begins to ache and sweat. My neck tightens, and I feel pressure like a thumb rammed up under my jaw. Nausea sweeps over me. My pulse races, my head throbs. By midnight, steamy sweat rolls off my hot skin, and I roll back and forth in anguish. My God, I have poisoned myself.

E

ACH BUBBLE AND RIPPLE

has been frozen in white ice streaming down over the precipice like the long frosty beard of Old Man Winter. The motion of the torrent is stopped, awaiting the thaw of spring. Within the frigid shell, the waterfall continues to thunder downward, splashing up into my glass, which rattles with stark blue shards of ice. The sparkling, effervescent liquid is held toward my lips, but my swooning head keeps dropping back from it. I open my eyes so I do not have to look at it any more.

Nausea strangles me. My tongue feels like a toad in my mouth. I can stand it no longer. Desperately I pull out a pint of my precious reserve, unscrew the cap, and pull on the bag. The water sits in my cheeks for a moment before I push my toady tongue upward and squirt it down my throat in an effort to douse the blaze in my belly. Another mouthful. The conflagration flickers. Another, then another. The pint bag hangs flaccid. The pyromaniac surrenders. Nausea is drowned. I sleep.

In the morning I am weak, but I am able to catch my eleventh triggerfish and refortify myself with its fresh organs and with sticks of dorado. I am back in the battle.

APRIL

2

DAY

57

Sticky gum has separated and clotted on the back of the remaining remnants of repair tape. I scrape up a small ball of gum with my knife and push a little plug of the goop through the hole in the solar still. I squish it over on both sides like a rivet. With the piece of repair tape wedged in over the gooey rivet, the replaced patch is markedly improved, gives my lungs a furlough, and keeps the blasted salt in the ocean where it belongs.

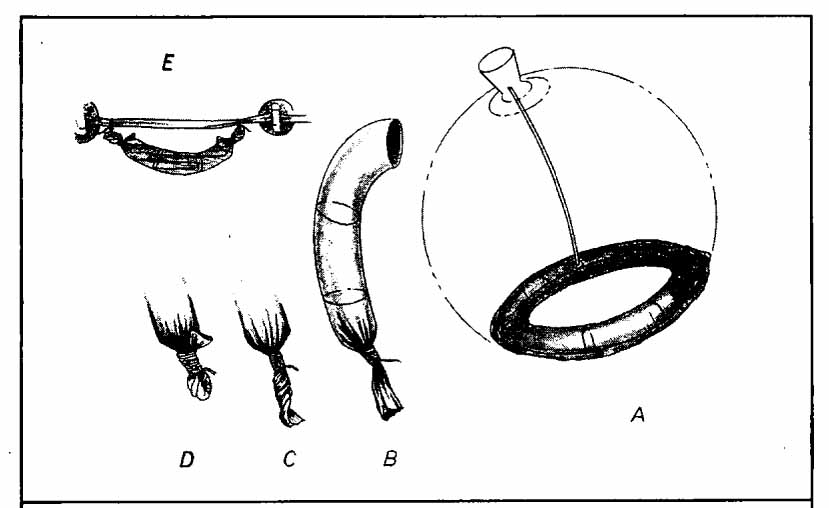

There's no telling how long the still will last. Buddha's bellybutton is getting bigger. I'd better collect and store as much water as I can now. The ballast ring from the cut-up still makes two decent containers. I cut it in half and bind up one end of each half. I can easily pour water into the open ends, which are about three inches in diameter, then lash them up. If it comes to it, I'll store tainted rainwater in these containers. The drainage tube may serve for administering a foul enema.

(A) I cut the ballast ring from the cut-up solar still. I slice this in half so that I can easily fill it through the open mouth on one end. (B) I tightly tie up one end, but it still leaks quite a lot so (C) I twist the tail and (D) pull it back upward and securely lash it up. Amazingly it still leaks, albeit at a very slow pace. After the container is filled, I repeat the closure process on the other end and (E) hang the container horizontally from the interior handline. This keeps the ends up and prevents leakage.

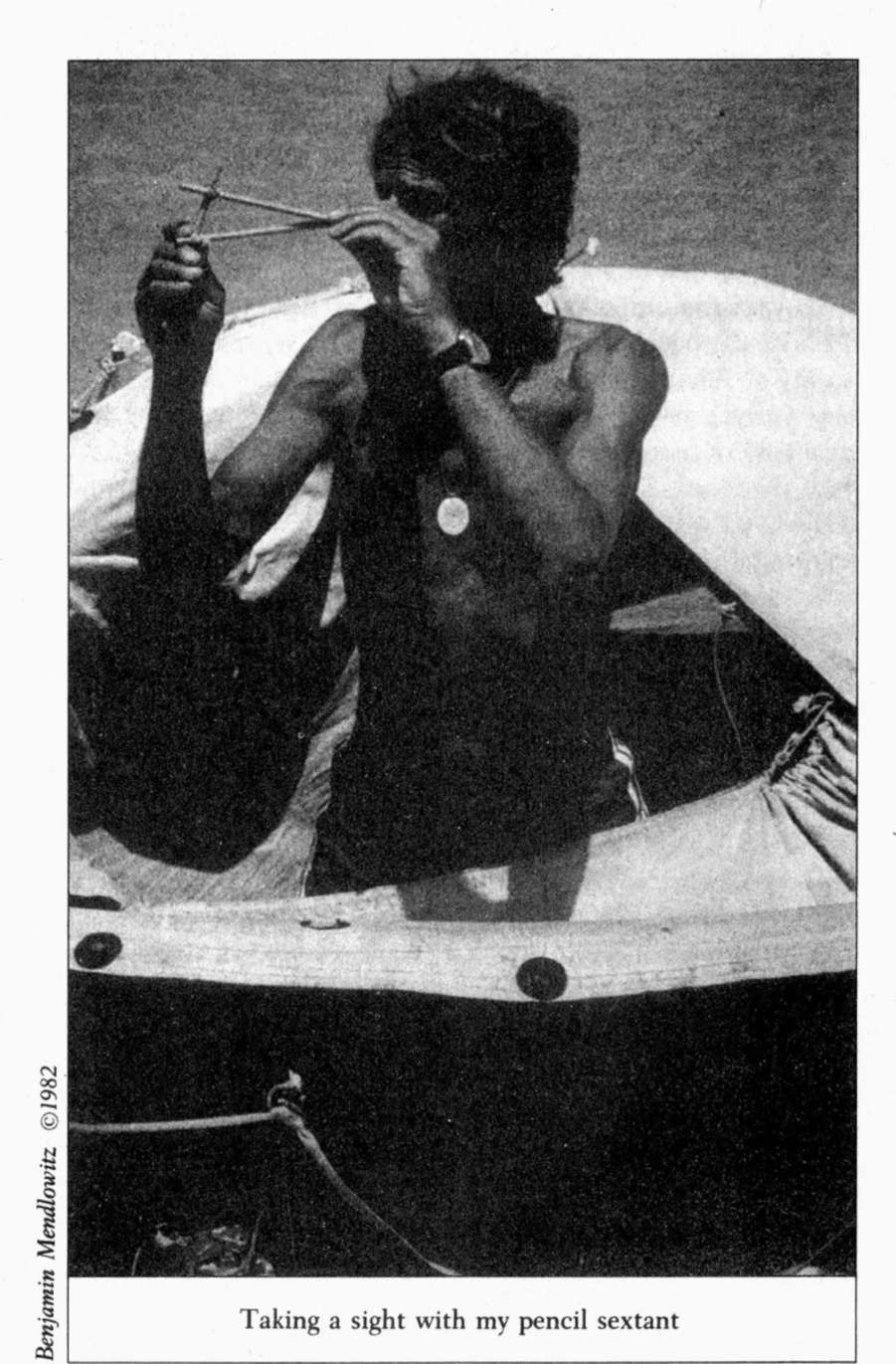

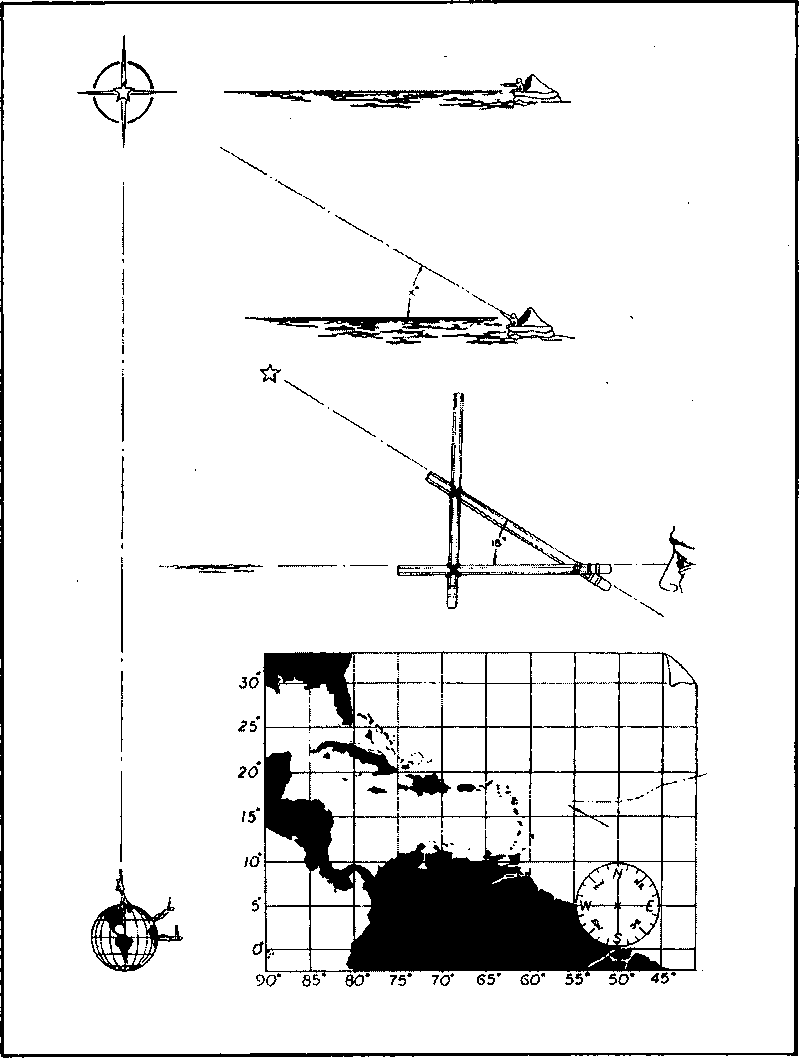

The wind is blowing us more northerly. Time to fix latitude. I lash three pencils into a triangle to make a low-budget sextant. Sextants are fancy protractors with mirrors that allow the navigator to look at the horizon and a star or planet at the same time. Early predecessors of the sextant include the cross-staff and backstaff made of wood. My instrument is even more primitive, since I cannot view both the stars and the horizon at the same time. Instead, I must move my head up and down, first viewing a star along one pencil and then the rim of the world along the other, while attempting to hold the instrument still. I will try it this evening.

Above Antigua the West Indies begin to bend off westward. If I drift above eighteen degrees latitude, I'll have to last another twenty or thirty days to reach the Bahamas. Guadeloupe is the most eastern island in the West Indies group. I'm aiming for seventeen degrees latitude. If a navigator stands on the North Pole, the North Star will sit directly overhead at ninety degrees to the horizon in all directions. The top of the world is at ninety degrees latitude. On the equator, at zero degrees latitude, Polaris dances right on the horizon. So latitude can be directly determined by the angle between the polestar and the horizon. I will try to measure the angle of the North Star to the horizon to give me my latitude.

Determining longitude is another matter entirely. To do so, the navigator equates arc with time. Each of the 360 degrees of the earth's circular belt line is divided into sixty minutes of arc. Each minute is one nautical mileâ6076 feet. Since the earth spins once every twenty-four hours, the heavenly bodies pass over fifteen degrees of longitude every hour, or fifteen minutes of longitude every minute. Some astronomers in Greenwich, England, began and ended their demarcation of the globe by running the longitude line of zero degrees through their little town. Longitude can be calculated by comparing the time when a heavenly body appears overhead to the time when it would be over Greenwich. The difference in time is then converted to arc, which tells the observer how far east or west of Greenwich he is. Not until the advent of accurate timepieces was it possible to fix longitude.

Captain Cook was one of the first to utilize the breakthrough invention called the chronometer. Until then, mariners commonly sailed north or south until they reached the latitude on which their port of destination lay. Then they would sail directly east or west. Latitude sailing, as it is called, figured on the altitude of the North Star, combined with my approximate speed and drift, which I have been keeping running track of, will give me a better idea of my position in this expanse of terrain barren of signposts and landmarks.

I measure off eighteen degrees from the chart's compass rose and set my sextant at this angle. Go west, young

Ducky,

and south.

The dorados strike hard all day, irritating my sores and infuriating me. The sky is clear again, the afternoon hot. Light winds swing to the south and push us north. Oh, hell! All night brilliant moonlight illuminates at least a hundred triggerfish and thirty escorting dorados that continually smash into

Ducky.

We go due north, then northeast, then east, right where we came from. Damn!

APRIL

3

DAY

58

By morning we've completed the loop and are back on course. I'm happy that my sextant says we're at seventeen degrees latitude, but it could be off by a degree or more. One degree the wrong way and I add a month to my trip. It's too close for comfort. And a day lost going nowhere. I can't expect consistent progress. Fifty-eight days, but I must be more patient and even more determined.

Bubbles gurgle out from

Ducky's

patch. I've got to pump every hour and a half to keep the tube tight. I tighten the tourniquet around the neck of the patch. The line struggles and then explodes, but the patch remains generally in place. I whip a noose of stronger cord around and pull it tight. Miraculously the bottom tube now holds air better than the top.

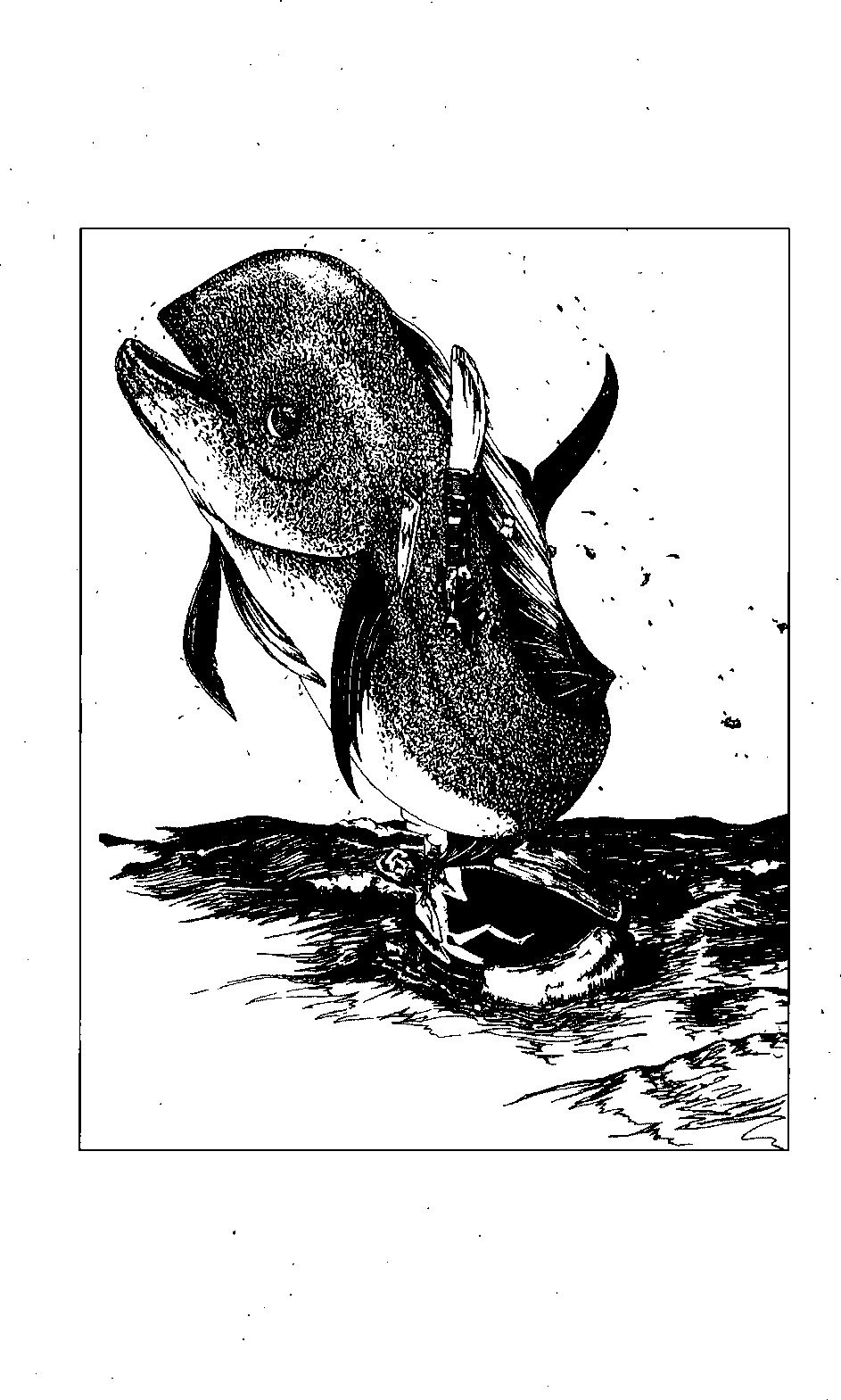

A number of dorados nudge my butt. They'll stick around for a while. Good time for a shot. I aim and fire. Miss. Again. Hit. A fine female. Lifted up, she glints in the sun. Her body pulses. She curls her head toward her tailâleft side, right side, left, right, faster and faster. My delicate lance sways to her rhythm. What a magnificent animal. In one smooth move that has become instinctive, I swing her inside and finish her off. Again I am provided with a buffer against starvation. Again I'm saddened by the loss of a companion. More and more I feel that these creatures exude a spirit that dwarfs mine. I don't know how to explain it rationallyâperhaps that's the point. I don't think that these fish reflect or think as we do; their intelligence is of a different kind. While I cogitate about truth and meaning, they find them in their immediate and intense connection to lifeâin bodysurfing down huge waves, in chasing flying fish, in fighting for life on the end of my spear. I have often thought that my instincts were the tools that allowed me to survive so that my "higher functions" could continue. Now I am finding that it is more the other way around. It is my ability to reason that keeps command and allows me to survive, and the things I am surviving for are those that I want by instinct: life, companionship, comfort, play. The dorados have all of that here, now. How I wish I could become what I eat.

B

ASIC NAVIGATION

. My position east-west was estimated by my speed of drift added to the approximate speed and direction of the current. I made the pencil sextant to help me estimate my latitude.

Upper left:

The North Star, or Polaris, sits directly above the North Pole. (Magnetic north is another matter entirely.) One can see that the man standing on the pole of the globe to the lower left looks straight up at Polaris, an angle of 90 degrees to his horizontal, or horizon. The man on the equator sees the polestar right on his horizontal plane. The man in the raft at the upper right is looking at the polestar on the horizon, so he must be on the equator The man on the globe who stands between the equator and the pole looks X degrees above his horizontal to see the polestar He is then at X degrees of latitude just like the man in the raft lower down. I lash together three pencils and set two of the arms at 18 degrees, which is my estimated latitude. I use the compass rose on the chart as a protractor, since it is conveniently divided up into 360 degrees. I must first line up the horizontal pencil with the horizon. Then, while trying not to move the instrument, I drop my eye so that I can look along the elevated pencil at Polaris. If Polaris is not in line, I adjust the angles of the pencils until it is, and then measure off my latitude from the compass rose. You can see on the chart that the islands bend off westward above 18 degrees and dramatically above 19. If I drift as high as 19 degrees, my voyage will last at least four days longer than at 18. If I go as high as 19.5 degrees, the voyage will lengthen by weeks, possibly months. My track is indicated by the broken line. The current flows in the direction of the arrow, trying to sweep me north. It will be very tight.