Adrift (22 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

This morning, finishing the last of the trigger, I am aware once again that I do not know where my next meal will come from. We overtake some large clumps of sargasso, which are no longer pristine and newly sprouted as they were far to the east. From the feathery branches I shake tiny shrimp, a half-inch-long fish, and a number of thick black worms bristling with white spines. I do not touch the worms. Chris made that mistake when we sailed to England, and he was left with a fistful of glasslike barbed slivers. I pick through the weed, searching for the small crabs, which try to scurry from my grasp. I collect them, pinching their shells so that they do not suffer long and do not escape.

Potbellied, mottled-skinned sargasso fish up to an inch long also fall out of the weed. I don't know that they are inedible, but I do find them very bitter. They do not taste too bad if I am careful not to eat their bloated bellies. And what are these gelatinous little slugs? They have four flipperlike jelly legs and a greenish and salty tasting body. I save the crabs and shrimp for dessert. Sometimes when I pop a crab into my mouth before killing it, the wee claws give my cheeks or tongue a little pinch, which makes me conscious of the small life I am taking.

In the early evening, rain clouds streak across the heavens, raising my hopes that I can rebuild my water stock. A light drizzle wets everything inside, since the canopy is now about as waterproof as a T-shirt. Early in the morning the drops fatten and strike with a tap, first one, a pause, then twenty, like spilled ball bearings, a pause, then a stampede of hard round bullets. I lunge for my kite and hold it out. The rain splatters on the Tupperware and off of the still. I'm able to collect ten ounces of good clear water and lick the residue of drops from the still. I feel quenched and confident again. By day's end my water supply will be completely replenished.

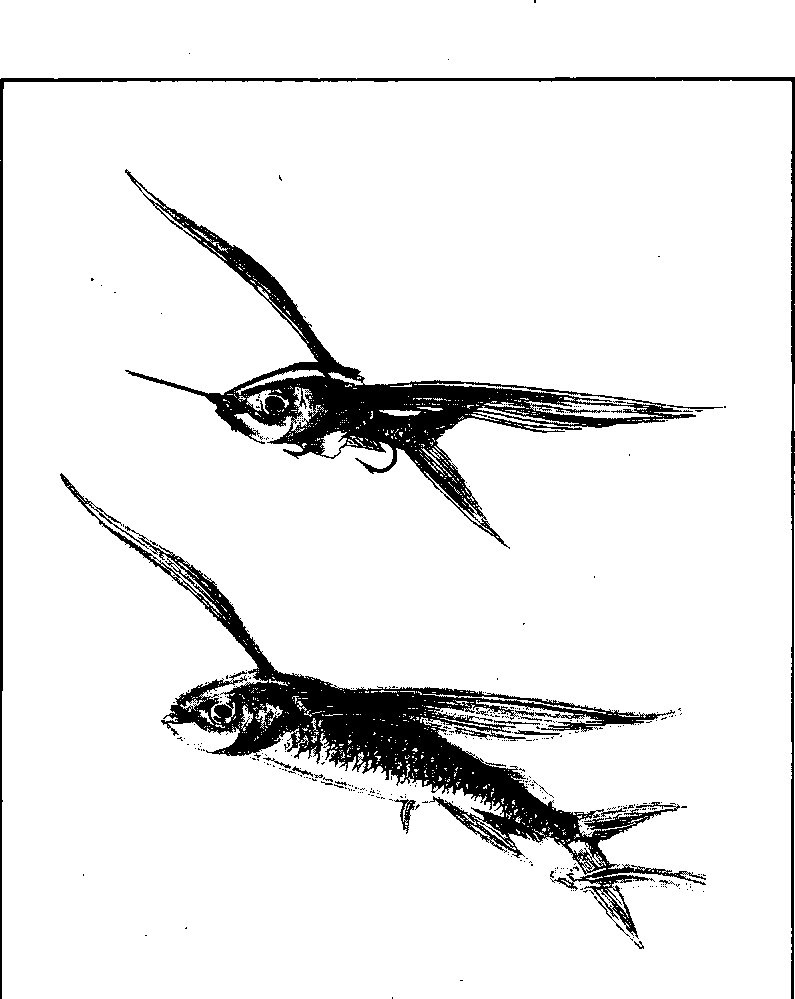

As I reseat myself on my cushion and flip the sleeping bag over my legs, I notice a small fin protruding from a crevice between my equipment bag and the raft's tubes. The rain has brought me an added reward. A large flying fish has lost its way in the downpour, brushed by me unnoticed, and crashed inside. While I await dawn, a small hurricane rattles the canopy and another flyer becomes lodged on the tent. After I have eaten the savory flesh of this flyer, I push the remaining head and tail together to see how they look. Not bad, not bad at all. I dig out my fishing gear and push the shank of a large treble hook from the back of the head out of the mouth of the flyer. I push the tail over the barbs of two large single hooks that I tie together, and then string these to the shank of the treble hook, using heavy sail twine. With the tail joined to the head this way, I've created a very short specimen of flying fish. The lure is so convincing that I'm tempted to bite it myself.

Fishing for dorados without wire leader is a pointless exercise, but it has dawned on me that there may be a strand of wire on the radar reflector. As I unroll the greased paper, a spidery web of Monel mesh and aluminum struts is revealed. The sea has also invaded here and has caused metallic sores. Electrolytic corrosion has eaten gaping, encrusted ulcers through the aluminum struts. However, there is a strong piece of stainless-steel wire, about eighteen inches long. I take note of the other valuable bits of metal and fasteners and pack the reflector away again.

The dorados have recently been shy of my spear, but they seem particularly voracious. I cast out a bit of trigger offal, and they leap upon it like frenzied sharks. I fling my lure out and work it aft, thirty feet, fifty feet, a hundred. I see it wiggling just under the crystal surface. A flash of indigo and snow whips by in front of it. The strike is hard. A jerk, another jerk, and then nothing. I watch the dorado dart off into the distance.

He has struck at the head of the lure. It seems that dorados often eat their meals head first, at least judging from the remains that I've taken from their stomachs. I have often noticed that the dorados travel in male-female pairs. I now believe that the pairing may serve more than one purpose. Perhaps one fish herds prey into the jaws of a companion who waits in the prey's path. If the herding dorado can catch the flyer from behind, so much the better for him or her. I can only make wild guesses about the dorados' behavior because I can observe them only when they are near me, a hundred feet away at most. If only I could swim with them to study the intricacies of their private lives.

I reset my lure with the remaining flying fish head. This time I'll give it enough slack to be swallowed. The dorado soon approaches. I give a few feet of line, stalling the midget flyer. He swallows. Take it in, deeply now. I yank to set the hook. Got him! The dorado thrashes forward as if engaging afterburners, flips his head, neatly bites the line off just ahead of the wire, and is gone. I will never catch a dorado by line. I must return to the spear.

The lure that I make from a flying fish is so convincing I'm tempted to bite it myself.

I figure I'm about 450 miles from Antigua. Could be off 100 miles either way, maybe more. Another eighteen days. Humph. At the beginning of this voyage, eighteen days was too much to ask for. Now I demand it.

As my equipment continues to wear out and break, and as my living corpse of a body continues to decompose, I must try harder to prepare for every eventuality. Only a few flares left. Well past the lanes. The islands still a long way off. But I'm too close now and have come through too much to let go.

At dusk in lumpy seas I spear a female dorado. In the course of the melee, the sun sinks, and a pool of ocean flows around my knee. Somehow the spear tip has pierced the floor. It's too small a slit to fit a plug into, so I take my knife out and increase the damage. No sweat. Its big enough now to ram a plug in, screw tight, and bind up with codline. Why, looky there, doesn't even leak a drop, even pulls the baggy floor a little tighter. I should have done this to the other holes in the bottom, and will if the patches come off again.

Inside the dorado is another mackerel-like fish, though smaller and more digested than the last. I can't get the flashlight to work, so I break out one of my two Lumalights. When the light stick is bent, two chemicals mix and give off a greenish glow. Rich fare is spread out on the board before me: two livers, a sac of eggs, two kinds of meat, and a full half pint of water. I eat by green candlelight. Things are looking up.

Showers come in the night and soak everything, but I only collect a little water. A ship heading west passes too far away to see my next-to-last parachute flare. A month ago I would have fired off three or more flares, but now I am much more realistic. I'll wait for a ship that is in a better position to see me. I can't afford to waste flares. Besides, I am getting very confident, perhaps too confident, that if a ship does not pick me up I will still make it to the islands. The overcast morning ruins my chances of distilling water, but I remain undaunted. Here's a breakfast fit for King Kong: huge steaks, a quarter pound of eggs, hearts, eyes, and a scraping of fat. Yum!

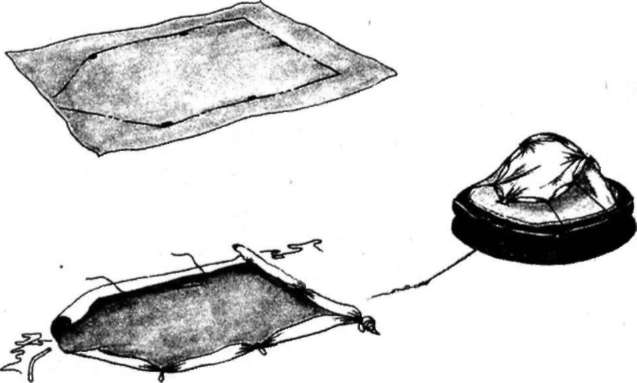

I'm in pretty warm waters now. Even if I get soaked, I'm not going to die of hypothermia overnight. Rain, at least a light shower, is becoming an almost daily occurrence. The space blanket can be risked for other purposes. I turn it into a water collection cape for the back of the canopy, rolling the edges to act like gutters. It's wide at the top, along the canopy arch tube, and funnels to a point, which I drag through the leaky observation port. Any waves sloshing over the canopy, as well as any rain, will now pour in as if through an open faucet. However, the back of the canopy is so leaky now that water pours in from all over. The cape covers most of the aft side, which is more weathered and less waterproof than the front. It makes the back a lot drier, though rain and spray still make their way around and under the cape. The cape catches about sixty to seventy percent of the water and drains it down through the faucet, so it is much easier to catch than when it poured in at random. I can hang the Tupperware box under the tap and bail it out with my coffee can, or I can put the can directly under the tap.

As I pick through more seaweed, a fish, too thin to be a dorado but of the same length, flits across my peripheral vision. Twice now I've gotten a glance of this fish. A barracuda? A shark? It's not important. What is important is that there are new species in my world. Something is happening. I can feel it, like a scout who feels the warmth of ashes and knows how recently men sat around the campfire.

New bird life shows its wings. In the distance, two birds fight. Perhaps they are gulls, but more likely they're terns. One of the charts from Robertson's book shows that the migration path of terns crosses my approximate position.

Sometimes you can use techniques that were developed by the South Seas islanders to tell if there is land ahead. You look for such indications as wave formations as they hit a shore and bounce back out to sea, rising cumulus clouds that skyrocket to great heights from thermal currents over the land, phosphorescent lines in the water at night, and so forth. I haven't detected any of these things. The most reliable method is to see land itself. But sighting land from a distance is always a tricky problem. When clouds are above you, they appear to move quickly. But as they near the horizon, you look through the atmosphere at an oblique angle and the clouds appear to move slower and slower while they also become darker. Cumulus clouds take on the illusory form of high volcanic rims or low, flat islands. Some remain still for so long that you begin to believe they are solid earth. Only by very long observation can the sailor distinguish land from clouds.

I make a water collection cape from the remaining part of the space blanket (part of the blanket I used previously to make a kite). (A) I plan out the shape and poke "buttonholes" in the blanket, through which I can thread twine to tie it up and to act as anchoring points. (B) I roll the sides to act like gutters, directing most of the water down to the apex of the point to the left. In the point I tie in a piece of tubing to act as a drain. I will pull this apex and drain through the observation port on the back of the raft. I can then direct the drain into a water container. Through the buttonholes, I tie string, and each knot is fitted with a loop to which I attach lanyards that run down to the raft's exterior handline. (C) The water collection cape is shown in position, with the point pulled through the observation port, the lanyards pulling it down and spreading it out as much as possible, and the top gutter lying along the ridge of the arch tube.

When Chris and I were approaching the Azores, I sighted a light gray conical shape among the high, fluffy cumulus. It did not move for several hours, slowly grew more distinct, and then extended itself down. We had sighted Faial from forty miles out, while the lower parts of the island were hidden in white haze at sea level. On the other hand, I once was less than a mile from thousand-foot cliffs in the Canaries on a sunny, clear day, when the sun illuminated some haze and the whole island disappeared. I desperately hope that I have underestimated my speed and that of the current. I've tried to be conservative. I watch for a stable form at the horizon, one that will stay put and turn green, but each shape I see slowly transforms itself into a winged horse or angel and flies off beyond sight.

It is the end of March. Will April showers bring May flowers, or will the first of April be a cosmic joke? Thought you'd make it, did you? Well, April fool!

APRIL

1

DAY

56

Clouds drop a light shower to test my water-catchment system. I get about a pint, but upon tasting it I find that it's still badly tainted with foul orange particles from the canopy. My catchment cape isn't as effective as I had hoped. There's still too much water draining down the canopy. This foul water drains through the same hole in the canopy as the clean water from the catchment cape. Maybe the foul water will be drinkable if I cut it with good water. I try a fifty-fifty ratio. It's still so gross that it's all I can do not to barf. Maybe if I cut it again with water from the still...

The sun peers out from behind the wall of gray and sets the solar still to working. Dancing droplets pirouette into the collection bag. The still keeps slumping over. The hole in its skirt must be getting critically large. I have to blow it up every ten or fifteen minutes. Production seems good, too good. I try to ignore the fact that the distilled water is growing salty. I'm dreadfully thirsty. The sea itself isn't so bad. If I mix the salty distilled water with the tainted fresh water, that should help dilute both the salt and the wretched flavor. When I get it all mixed together, I have a concoction that would be a fitting test of manhood in any ancient tribal ritual, a mix of water, rock salt, and vomit. Get rid of it. Don't want to pollute tomorrow's water production, but can't afford to throw it out. I hold my nose and swallow. The liquid slightly burns as I gulp it down.