Adrift (27 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

T

HE EVENING SKIES

of my seventy-fifth day are smudged with clouds migrating westward. A drizzle falls, barely more than a fog, but any amount of saltless moisture causes me to jump into action. For two hours I swing my plastic buckets through the air, collecting a pint and a half. My catchment systems

will

do the trick.

As long as the waves are not too large, I do not worry about capsizing, so I curl up and sleep against the bow. These days it takes so long to choke out the pain and fall asleep. When I do, it is only an hour or less before a sharp stab from a wound or sore awakens me.

I arise to survey the black waters, which occasionally flash with phosphorescent lines from a breaking wave or the flight of a fish. A soft glow looms just to the south of dead ahead. And there, just to the north, is another. A fishing fleet? They do not move. My God, these are no ships! It is the nighttime halo of land that I detect! Standing, I glimpse a flip of light from the side. A lighthouse beam, just over the horizon, sweeps a wide bar of light like a club beating out a rhythmâflash, pause, flash-flash, rest; flash, pause, flash-flash. It

is

land. "Land!" I shout. "Land ho!" I'm dancing up and down, flinging my arms about, as if hugging an invisible campanion. I can't believe it!

This calls for a real celebration! Break out the drinks! In big, healthy swallows, I down two pints. I swagger and feel as lightheaded as if it were pure alcohol. I look out time and again to confirm that this is no illusion. I pinch myself. Ouch! Yes, and I have gotten the water to my lips and down my throat, which I've never been able to do in a dream. No, it isn't any dream. Oh real, how real! I bounce about like an idiot. I'm having quite a time.

O. K., now, calm down. You aren't home yet. What lighthouse is that? Antigua doesn't make sense. Are you north or south?

Ducky

is aimed down the empty corridor between the two glows that I see. When I get closer maybe I can paddle some, or maybe I can strap the paddles onto

Ducky's

tubes to act like center-boards. Even if I can't hit land, the EPIRB will surely bring help. When the sun rises I'll flick the switch one last time.

I can hardly sleep but manage to drop off for a half hour now and again. Each time I awaken, I look out to confirm that this isn't the ultimate elaborate dream. Another glow begins to emerge dead ahead. Morning, I hope, will reveal the rim of an island down low on the horizon, close enough to reach before nightfall. A landing in daylight will be dangerous enough. If I reach the island tomorrow night ... Well, one thing at a time. Rest now.

APRIL

21

DAY

76

Dawn of the seventy-sixth day arrives. I can't believe the rich panorama that meets my eyes. It is full of green. After months of little other than blue sky, blue fish, and blue sea, the brilliant, verdant green is overwhelming. It is not just the rim of one island that is ahead, as I had expected. To the south a mountainous island as lush as Eden juts out of the sea and reaches up toward the clouds. To the north is another island with a high peak. Directly ahead is a flat-topped isleâno vague outline, but in fall living color. I'm five to ten miles out and headed right for the center. The northern half is composed of vertical cliffs against which the Atlantic smashes to foam. To the south the land slopes down to a long beach above which a few white buildings perch, probably houses.

Close as I am, I'm not safe yet. A landing is bound to be treacherous. If I hit the northern shore, I run the risk of being crushed against the sharp coral cliffs. To the south I'll have to rake across wide reefs before I hit the beach. Even if I get that far without being ripped to ribbons, I doubt I'll be able to walk or even crawl to get help. One way or the other, this voyage will end today, probably by late afternoon.

I flip on the EPIRB, and for the first time I break out the medical kit. As with all of my supplies, I have been saving it until I absolutely needed it. I take out some cream, smear it all over my sores, and fashion a diaper from the triangular bandage. I'll try to coerce

Ducky

to sail around the south side of the island, so I don't have to land through the breakers on the windward side. If

Ducky

refuses, I'll go for the beach. I'll need all the protection I can get. I'll wrap the foam cushion around my torso, which will keep me afloat and serve as a buffer against the coral. I'll cut off

Rubber Ducky's

canopy, so that I won't get trapped inside and so I can wrap my legs and arms with the fabric.

I'll try to keep

Ducky

upright and ride her in, though the bottom tube will certainly be torn to bits. Everything must be orderly and secure. I rummage around, throwing out pieces of junk that I won't need and making room in my bags for the first aid kit and the other necessities. I gnaw on a couple of fish sticks, but they taste like lumps of tallow. I can survive with no more food. My doggies nudge at me. Yes, my friends, I will soon leave you. On what separate paths will we travel? I pitch the remaining rancid fish sticks and save only a few of the dried amber ones as souvenirs. Ah, yes, another pint of water to fortify myself for the landing.

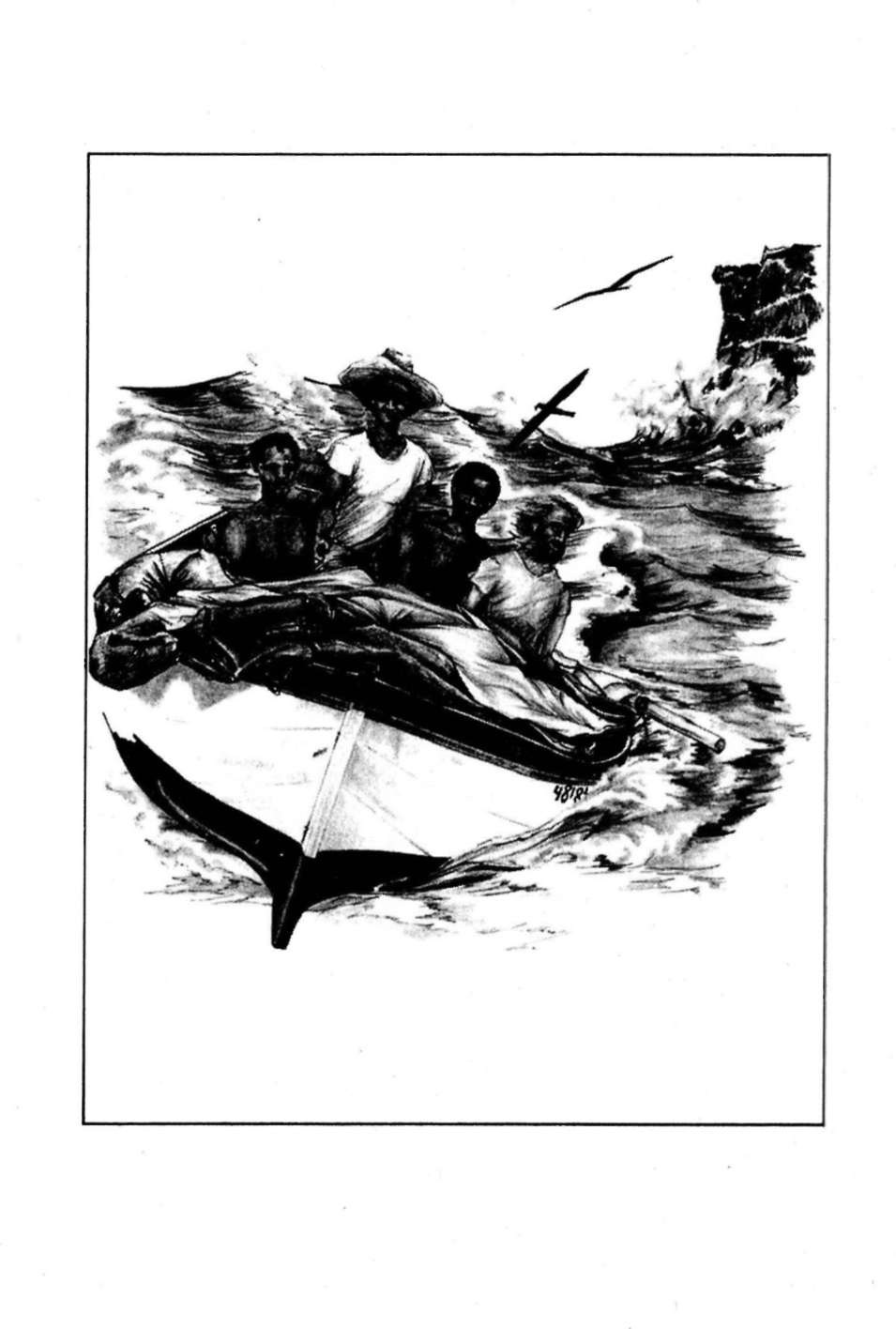

As each wave passes, I hear something new. RRrrr ... RRrrr ... It grows louder. An engine! I leap to my knees. Coming from the island, a couple of hundred yards away, a sharp white bow, flared out at the rail, pitches forward against a wave and then crashes down with a splash. The boat climbs and falls, getting closer and closer. It's small, maybe twenty feet, and is made of roughhewn wood painted white, with a green stripe around the gunwale. Three incredulous dark faces peer toward me. Jumping to my feet, I wave to them and yell, "Hello!" They wave back. This time I have definitely been seen. I am saved! I can't believe it, just can't believe ... Nearly over. No reef crossing, no anxious awaiting of an airplane. Two of the men are golden mahogany in color, and the third is black. The one at the helm wears a floppy straw hat with a wide brim that flaps up and down. His T-shirt flags out behind him as he rounds his boat ahead of me and slides to a halt. The three of them are about my age and seem perplexed as they loudly babble to one another in a strange tongue. It's been almost three months since I've heard another human voice.

"

Hablar español?

" I yell.

"No, no!" What is it that they say?

"

Parlez-vous français?

" I can't make out their reply. They all talk at the same time. I motion to the islands. "What islands?"

"Aahh." They seem to get it. "Guadeloupe, Guadeloupe." French. But it sure isn't like any French I've ever heard. It's Creole, I learn later, a rapid-fire, pidgin French. In a few minutes I figure out that the blackest of them is speaking English, with a Calypso beat and heavy Caribbean accent. I'd probably have trouble comprehending another New Englander at this point, but I begin to put it all together.

We sit in our tiny boats, rising and falling on the waves, only yards apart. For several moments we stop talking and stare at one another, not knowing quite what to say. Finally they ask me, "Whatch you doing, man? Whatch you want?"

"I'm on the sea for seventy-six days." They turn to each other, chattering away loudly. Perhaps they think I embarked from Europe in

Rubber Ducky III

as a stunt. "Do you have any fruit?" I ask.

"No, we have nothing like that with us." As if confused and not knowing what they should do, the ebony one asks instead, "You want to go to the island now?"

Yes, oh, definitely yes, I think, but I say nothing immediately. Their boat rolls toward me and then away, empty of fish. The present, the past, and the immediate future suddenly seem to fit together in some inexplicable way. I know that my struggle is over. The door to my escape has been fortuitously flung open by these fishermen. They are offering me the greatest gift possible: life itself. I feel as if I have struggled with a most demanding puzzle, and after fumbling for the key piece for a long time, it has fallen into my fingers. For the first time in two and a half months, my feelings, body, and mind are of one piece.

The frigates hover high above, drawn to me by my dorados and the flying fish on which they both feed. These fishermen saw the birds, knew there were fish here, and came to find them. They found me; but not me

instead

of their fish, me

and

their fish. Dorados. They have sustained me and have been my friends. They nearly killed me, too, and now they are my salvation. I am delivered to the hands of fishermen, my brothers of the sea. They rely on her just as I have. Their hooks, barbs, and bludgeons are similar to my own. Their clothing is as simple. Perhaps their lives are as poor. The puzzle is nearly finished. It is time to fit the last piece.

"No, I'm O.K. I have plenty of water. I can wait. You fish. Fish!" I yell as if reaching a revelation. "Plenty of fish, big fish, best fish in the sea!" They look at each other, talking. I urge them. "Plenty of fish here, you

must

fish!"

One bends over the engine and gives the line a yank. The boat leaps forward. They bait six-inch hooks with silvery fish that look like flyers without big wings. Several lines are tossed overboard, and in a moment, amidst tangled Creole yells and flailing arms, the engine is cut. One of them gives a heave, and a huge dorado jumps through, the air in a wide arc and lands with a thud in the bottom of the boat. They roar off again, and before they've gone two hundred yards they stop and yank two more fat fish aboard. Their yelling never stops. Their cacophonous Creole becomes more jumbled and wild, as if short-circuiting from the overload of energy in the fishing frenzy. Repeatedly they open the throttle and the boat leaps forward. They bail frantically, cast out hooks, give their lines a jerk, and stop. The stern wave rushes up, lifts and pats the boat's rear. More fish are hauled from the sea.

I calmly open my water tins. Five pints of my hoarded wealth flow down my throat. I watch the dorados below me, calmly swimming about. Yes, we part here, my friends. You do not seem betrayed. Perhaps you do not mind enriching these poor men. They will never again see a catch the likes of you. What secrets do you know that I cannot even guess?

I wonder why I chanced to pack my spear gun in my emergency bag, why

Sob

stayed afloat just long enough for me to get my equipment. Why, when I had trouble hunting, did the dorado come closer? Why did they make it increasingly easier for me as I and my weapon became more broken and weak, until in the end they lay on their sides right under my point? Why have they provided me just enough food to hang on for eighteen hundred nautical miles? I know that they are only fish, and I am only a man. We do what we must and only what Nature allows us to do in this life. Yet sometimes the fabric of life is woven into such a fantastic pattern. I needed a miracle and my fish gave it to me. That and more. They've shown me that miracles swim and fly and walk, rain down and roll away all around me. I look around at life's magnificent arena. The dorados seem almost to be leaping into the fishermen's arms. I have never felt so humble, nor so peaceful, free, and at ease.

Tiny letters on the boat's quarters spell out her name,

Clemence.

She roars off one way and then the other, circling around

Rubber Ducky,

around and around. The men are pulling in a fish a minute. They swing by every so often to see if I'm all right. I wave to them. They come very close, and one of them holds out a bundle of brown paper as

Clemence

glides by. I unwrap the gift and behold a great prize: a mound of chipped coconut cemented together with raw brown sugar and capped with a dot of red sugar. Red! Even simple colors take on a miraculous significance.

"Coco

sucré,

" one yells as they roar off again to continue the hunt. My smileâGod, it's so strange to smileâfeels wrapped right around my head. Sugar and fruit at the same time. I peel off a shard of coconut and lay it upon my watering tongue. I carefully chip away at the

coco sucré

like a sculptor working on a piece of granite, but I eat it all, every last bit of it.

Slowly the dorados below thin out. The fishermen are slowing down. A doggie comes by every so often as if to say farewell before shooting off after the hook. The sun is getting high, and I am very weary. Stop fishing now. Let's go in. Within a half hour, I am draped over the bow, trying to stay cool and conscious. Finally the massacre is over. It is time for my voyage to end.

T

HE FISHERMEN

pull up in front of

Ducky.

I swing my equipment bag over to them. Then they grab me with helping hands and I clamber aboard. I slip into the bottom of the boat and sit among dozens of dorados and a few kingfish and barracuda. I recognize my doggies. There is the one I plucked from the seaâ"There, is that what you want, stupid fish!"âsimply in order to scare him away. There is the one that bit through my fishing line ahead of the wire. And there is the lovely female that would coyly brush against the raft, always just to the right of where I was aiming. The emerald elders are nowhere to be seen.