Adrift (2 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

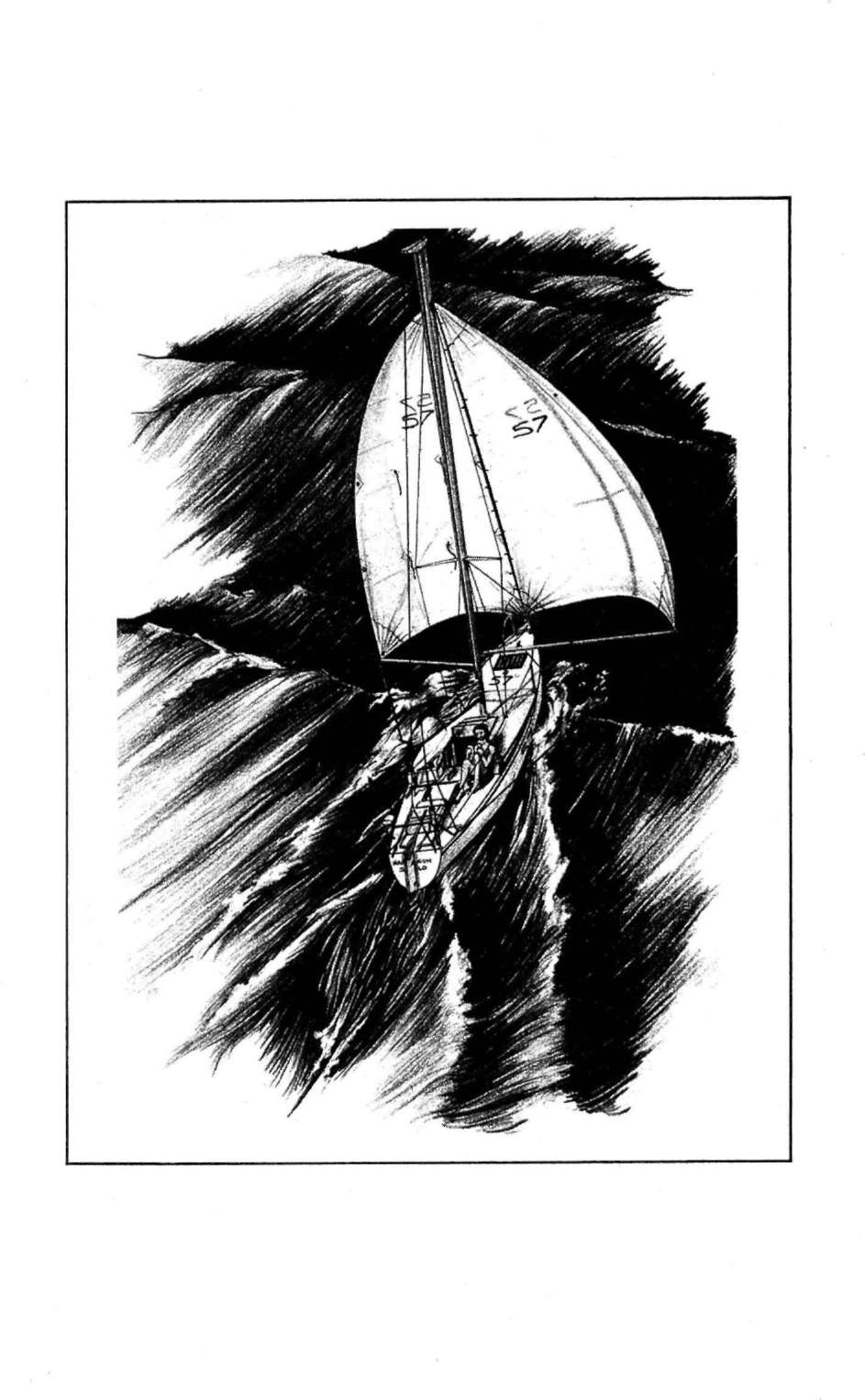

In 1980 I sold my twenty-eight-foot trimaran and put all of my resources into the creation of

Napoleon Solo,

a small cruiser. I relied on a great deal of aid from my ex-wife, Frisha Hugessen, my good friend Chris Latchem, and a host of others. The design was unusual, though not at all radical. We took pains to create a handsome, meticulously constructed cold-molded craft, excellent in light airs and well-balanced and forgiving in heavy weather.

Solo

became much more than a boat to me. I knew her every nail and screw, every grain of wood. It was as if I'd created a living being. Sailors tend to feel that way about their boats. Chris and I gave

Solo

a harsh thousand-mile shakedown cruise from Annapolis to Massachusetts through late-fall gales. By the spring of 1981, I was ready to follow in Manry's wake.

I was not interested in setting a record as Manry had done.

Solo

was just over twenty-one feet long. There weren't many boats of her size that had made the crossing, but there had been a few as small as twelve feet. For me the crossing was more of an inner voyage and a pilgrimage, of sorts. It would also serve as a measuring stick for my competence as a seaman, a designer, and a craftsman. I figured that if I made it to England safely, I'd have accomplished every major goal I'd ever set for myself. From England I would continue south and west, measuring

Solo's

performance in a single-handed transatlantic race called the Mini-Transat. That would carry me to Antigua. In the spring I would return to New England, thereby completing a circumnavigation of the North Atlantic. To qualify for the Mini-Transat, I had to sail six hundred miles alone in

Solo,

so I entered the Bermuda 1â2 Race and sailed from Newport to Bermuda. From there I would make the crossing to England with Chris.

When I departed the United States, it was with everything I owned, except for some tools. Few insurance brokers had wanted to talk to me, and those who did set such exorbitant premiums that it would cost less to buy materials for a second boat. I decided to take the risk. I told people that the worst that could happen was that I'd be killed, in which case I wouldn't be worried about collecting any insurance money. The second worst thing would be to lose

Solo.

It would take a while to recover, but I would. I knew plenty of other people who had lost their boats and recovered.

Many of my friends still couldn't understand why I wanted to undertake such a voyage, why I couldn't test myself without crossing the Atlantic. But there was more to the crossing than simply putting myself to the test. From the first time I ventured from the shore in a boat, I felt that my spirit was touched. On my first offshore trip to Bermuda, I began to think of the sea as my chapel. It was my soul that called me to this pilgrimage.

One friend suggested I write down my thoughts for the benefit of those who thought I was mad. While waiting for Chris in Bermuda, I sat beneath a palm tree and wrote the following: "I wish I could describe the feeling of being at sea, the anguish, frustration, and fear, the beauty that accompanies threatening spectacles, the spiritual communion with creatures in whose domain I sail. There is a magnificent intensity in life that comes when we are not in control but are only reacting, living, surviving. I am not a religious man per se. My own cosmology is convoluted and not in line with any particular church or philosophy. But for me, to go to sea is to get a glimpse of the face of God. At sea I am reminded of my insignificanceâof all men's insignificance. It is a wonderful feeling to be so humbled."

The Atlantic crossing to England with Chris was exhilaratingâgales, fast runs, whales, dolphins. It was the stuff adventure is made of. And as we approached the coast of England, I felt I was ending the whole experience that had begun at my birth, and beginning a new one.

I

T IS LATE

at night. The fog has been dense for days.

Napoleon Solo

continues to slice purposefully through the sea toward the coast of England. We should be getting very close to the Scilly Isles. We must be very careful. The tides are large, the currents strong, and these shipping lanes heavily traveled. Both Chris and I are keeping a sharp eye out. Suddenly the lighthouse looms on the rocky isles, its beam high off the water. Immediately we see breakers. We're too close. Chris pushes the helm down and I trim the sails so that

Solo

sails parallel to the rocks that we can see. We time the change in bearing of the lighthouse to calculate our distance awayâless than a mile. The light is charted to have a thirty-mile ran^e We are fortunate because the fog is not as thick as it often is back in our home waters of Maine. No wonder that in the single month of November 1893 no fewer than 298 ships scattered their bones these rocks.

The next morning,

Solo

eases herself out of the white fog and over the swells in a light breeze. She slowly slips into the bay in which Penzance is nestled. The sea pounds against the granite cliffs of Cornwall on the southwest coast of England, which has claimed its own vast share of ships and lives. The jaws of the bay hold many dangers, such as the pile of rocks known as the Lizard.

Today the sky is bright and sunny. The sea is gentle. Green fields cap the cliffs. After our two-week passage from the Azores with only the smell of salt water in our lungs, the scent of land is sweet. At the end of every passage, I feel as if I am living the last page of a fairy tale, but this time the feeling is especially strong. Chris, who is my only crew, wings out the jib. It gently floats out over the water and tugs us past the village of Mousehole, which is perched in a crevice in the cliffs. We soon glide up to the high stone breakwater at Penzance and secure

Na

poleon Solo

to it. With the final neat turns of docking lines around the cleats, we conclude

Soto's

Atlantic crossing and the last of the goals that I began setting for myself fifteen years ago. It was then that Robert Manry showed me not only how to dream, but also how to fulfill that dream. Manry had done it in a tiny boat called,

Tinkerbelle.

I did it in

Solo.

Chris and I climb up the stone quay to look for customs and the nearest pub. I look down on

Solo

and think of how she is a reflection of myself. I conceived her, created her, and sailed her. Everything I have is within her. Together we have ended this chapter of my life. It is time to dream new dreams.

Chris will soon depart and leave me to continue my journey with

Solo

alone. I've entered the Mini-Transat Race, which is a singlehanded affair. I don't need to think about that for a while. Now it is time for celebration. We head off to find a pint, the first we've had in weeks.

The Mini-Transat runs from Penzance to the Canaries and then on to Antigua. I want to go to the Caribbean anyway. Figure I'll find work there for the winter.

Solo

is a fast-cruising boat, and I'm interested to see how she fares against the spartan racers. I think I have a shot at finishing in the money since my boat is so well prepped. Some of my opponents are putting in bulkheads and drawing numbers on sails with Magic Markers in frantic pandemonium before the start. I indulge in local pasties and fish and chips. My last-minute jobs consist of licking stamps and sampling the local brew.

It is not all fun and games. It is the autumn equinox, when storms rage, and within a week two severe gales rip up the English Channel. Ships are cracked in half and many of the Transat competitors are delayed. One French boat capsizes and her crew can't right her. They take to their life raft and manage to land on a lonesome, tiny beach along a stretch of treacherous cliffs on the Brittany coast. Another Frenchman is not so lucky. His body and the transom of his boat are found crumpled on the Lizard. A black mood hangs over the fleet.

I make my way up to the local chandlery for final preparations. It is nestled in a mossy alleyway, and no sign marks its location. No one needs to post the way to old Willoughby's domain. I was warned that he talks a tough line, but in my few visits I have warmed up to his cynicism. Willoughby is squat, his legs bowed as if they have been steam-bent around a beer barrel, causing him to walk on the sides of his shoes. He slowly hobbles about the shop, weaving back and forth like an uncanvased ship in a swell. Beneath a gray tousle of hair, his eyes are squinted and sparkly. A pipe is clamped between his teeth.

Turning to one of his clerks, he motions toward the harbor. "All those little boats and crazy youngsters down there, nothin' but lots of work and headaches, I can tell you." Turning back to me he mutters, "Here to steal more bosunry from an old man and make him work like the devil to boot, I bet."

"That's right, no rest for the wicked," I tell him.

Willoughby raises a brow and twirks the faintest wrinkle of a grin, which he tries to hide behind his pipe. In no time he is spinning yarns big enough to knit the world a sweater. He ran away to sea at fifteen, served on square-riggers in the wool trade from Australia to England. He's been round Cape Horn so many times he's lost count.

"I heard about that Frenchman. Why you fellas go to sea for pleasure is beyond me. 'Course we had some fine times in my day, real fine times we had. But that was our stock in trade. A fella who'd go to sea for pleasured sure go to hell for a pastime."

I can tell the old man has a big space in his heart for all nautical lunatics, especially the young ones. "At least you'd have somebody to keep you company then, Mr. Willoughby."

"It's a bad business I tell you, a bad business," he says more seriously. "Sorry thing, that Frenchman. What do you get if you win this here race? Big prize?"

"No, I don't know really. Maybe a plastic cup or something."

"Ha! A fine state of affairs! You go out, play tag with Neptune, have a good chance to end up in old Davy Jones' lockerâand for a cup. It's a good joke." And it is, too. The Frenchman has really affected the old man. He cheerily insists on slipping a few goodies onto my pile, free of charge, but his tone is somber. "Now don't come back and bother me any more."

"Next time I'm in town you can bet on me like the plague, or the tax man. Cheers!"

A little bell jingles laughingly as I close the door. I can hear Willoughby inside pacing to and fro on the creaking wooden floor. "A bad business, I tell you. It's a bad business."

The morning of the race's start, I make my way past the milling crowds to the skipper's meeting. Whether the race will start on time or not has been a matter of speculation for days. The last couple of gales that swept through had edged up to hurricane force. "Expect heavy winds at the start," a meteorologist tells us. "By nightfall they'll be up to force eight or so."

The crowd murmurs. "Starting in a bloody gale ... Quiet, he's not finished yet."

"If you can weather Finisterre you'll be okay, but try to get plenty of sea room. Within thirty-six hours, all hell is going to break loose, with a good chance of force ten to twelve and forty-foot waves."

"Lovely," I say. "Anybody want to charter a small racing boatâcheap?" The crowd's talk grows loud. Heated debate breaks out between the racers and their supporters. Isn't it lunacy to start a transatlantic race in these conditions? The talk subsides as the race organizer breaks in.

"Please! Look, if we postpone we might not get off at all. It's late in the year and we could get locked in for weeks. We all knew it would probably be tough going to the Canaries. If you can get past Finisterre, you'll be home free. So keep in touch, stay awake, and good sailing."

The quay around Penzance's inner harbor is packed with people gawking and snapping pictures, waving, weeping or laughing. They will soon return to the comfort of their warm little houses.

I yell "Cheerio!" as

Solo

is towed out between the massive steel gates, which are opened by the harbormaster and his men pacing round an antique capstan.

Solo

and I are as prepared as we can be. My apprehension gives way to high spirits and excitement. The seconds tick by. My fellow racers and I maneuver about the starting line, making practice runs at it, adjusting our sails, shaking our arms to get the butterflies out of our stomachs. Those prone to seasickness will have a hard time. Warning colors go up. Get ready. Waves sweep into the bay; the wind is already growing, a rancorous circus sky flies in from the west. I reign

Solo

in, tack her over. Smoke puffs from the starting gun; its blast is blown away in the wind before it reaches my ears.

Sob

cuts across the line leading the fleet into the race.