Adrift (5 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

The entrance fly on the tent-type cover snaps with a ripping sound each time the Velcro seal is blown by the wind. I must turn the raft or a breaker may drive through the opening. While on a wave peak, I look aft at Soto's deck mounting on the next swell. The sea rises smoothly from the dark, a giant sitting up after a sleep. There is a tight round opening in the opposite side of the tent. I stick myself through this observation port up to my waist. I must not let go of the rope to

Solo,

but I need to move it. I loop a rope through the mainsheet which trails from Soto's deck and lead it back to the raft. One end of this I secure to the handline around the raft's perimeter. The other I wind around the handline and bring the tail through the observation port. If

Solo

sinks I can let go of this tail and we will slip apart. Waitâcan't get back in ... I'm stuck. I try to free myself from the canopy clutching my chest. The sea spits at me. Crests roar in the darkness. I twist and yank and fall back inside. The raft swings and presents the wall of the tent to the waves. Ha! A good joke, the wall of a tent against the sea, the sea that beats granite to sand.

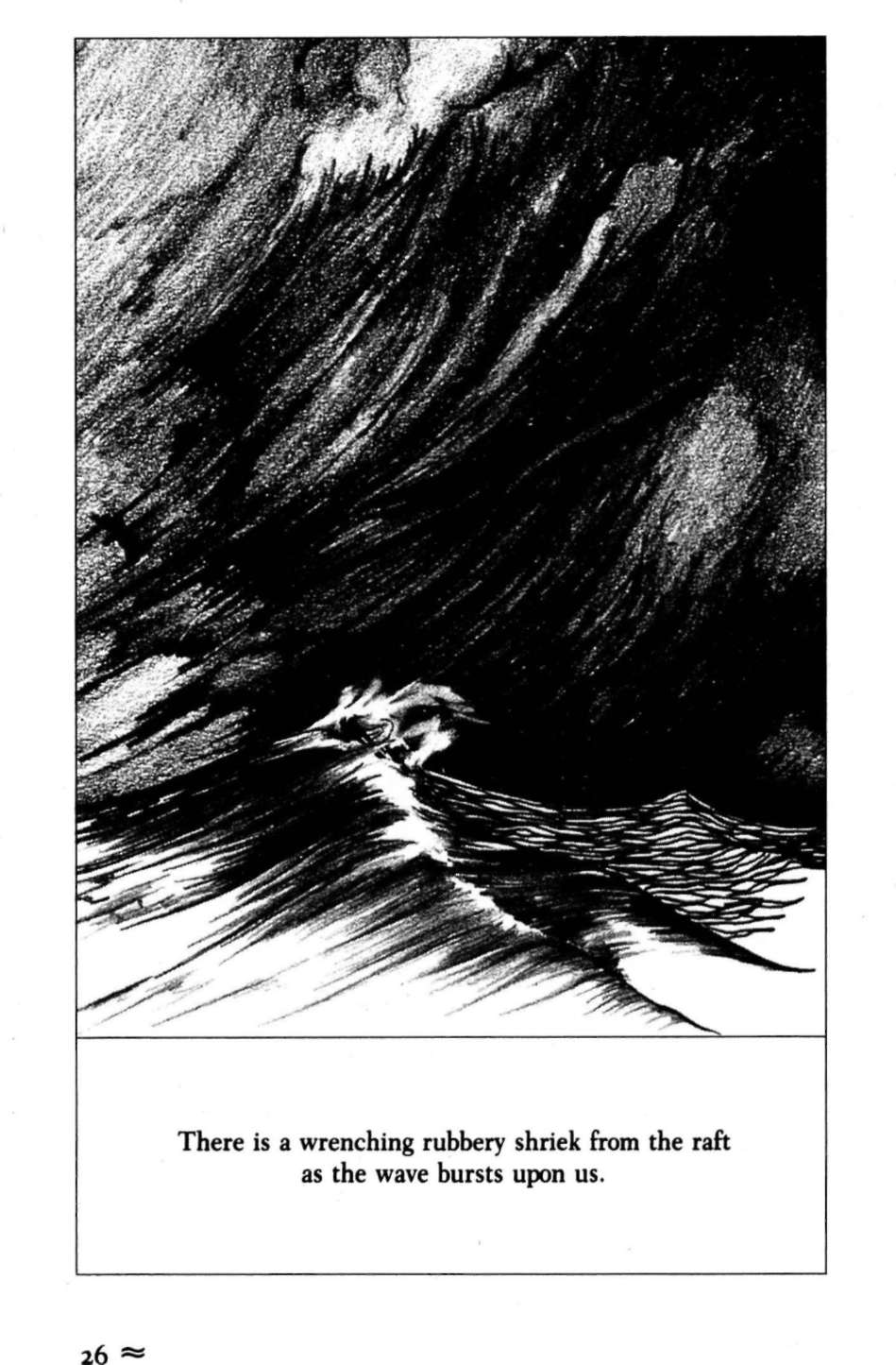

With a slipknot I tie Soto's line to the handhold webbing that encircles the inside of the raft. While frantically tying all of my equipment to the webbing, I hear rumbling well to windward. It must be a big wave to be heard so far off. I listen to its approach. A rush of water, then silence. I can feel it rising over me. There is a wrenching rubbery shriek from the raft as the wave bursts upon us and my space collapses in half. The windward side punches in and sends me flying across the raft. The top collapses and water shoots in everywhere. The impact is strengthened by the jerking painter, tied to my ship full of water, upwind from where the sea sprang. I'm going to die. Tonight. Here some 450 miles away from the nearest land. The sea will crush me, capsize me, and rob my body of heat and breath. I will be lost, and no one will even know until I'm weeks overdue.

I crawl back to windward, keeping one hand on the cord to

Solo,

the other hand clutching the handline. I huddle in my sodden sleeping bag. Gallons of water slosh about in the bottom of the raft. I sit on the cushion, which insulates me from the icy floor. I'm shivering but begin to warm up. It is a time to wait, to listen, to think, to plan, and to fear.

As my raft and I rise to the crest of a wave, I can see

Solo

wallowing in the following trough. Then she rises against the face of the next wave as I plummet into the trough that had cradled her a moment before. She has rolled well over now, with her nose and starboard side under and her stern quarter fairly high. If only you will stay afloat until morning. I must see you again, must see the damage that I feel I have caused you. Why didn't I wait in the Canaries? Why didn't I soften up and relax? Why did I drive you to this so that I could complete my stupid goal of a double crossing? I'm sorry, my poor

Solo.

I have swallowed a lot of salt and my throat is parched. Perhaps in the morning I can retrieve more gear, jugs of water, and some food. I plan every move and every priority. The loss of body heat is the most immediate danger, but the sleeping bag may give me enough protection. Water is the first priority, then food. After that, whatever else I can grab. Ten gallons of water rest in the galley locker just under the companionwayâforty to eighty days' worth of survival rations waiting for me just a hundred feet away. The raised stern quarter will make it easier to get aft. There are two large duffels in the aft cabin, hung on the topsides; one is full of foodâabout a month's worthâand the other is full of clothes. If I can dive down and swim forward, I may be able to pull my survival suit out of the fore-peak. I dream of how its thick neoprene will warm me up.

Waves continue to pound the raft, beating the side in, pouring in water. The tubes are as tight as teak logs, yet they are bent like spaghetti. Bailing with the coffee can again and again, I wonder how much one of these rafts can take and watch for signs of splitting.

A small overhead lamp lights my tiny new world. The memory of the crash, the rank odor of my surroundings, the pounding of the sea, the moaning wind, and my plan to reboard

Solo

in the morning roll over and over in my brain. Surely it will end soon.

FEBRUARY

5

DAY

1

I am lost about halfway between western Oshkosh and Nowhere City. I do not think the Atlantic has emptier waters. I am about 450 miles north of the Cape Verde Islands, but they stand across the wind. I can drift only in the direction she blows. Downwind, 450 miles separate me from the nearest shipping lanes. Caribbean islands are the closest possible landfall, eighteen hundred nautical miles away. Do not think of it. Plan for daylight, instead. I have hope if the raft lasts. Will it last? The sea continues to attack. It does not always give warning. Often the curl develops just before it strikes. The roar accompanies the crash, beating the raft, ripping at it.

I hear a growl a long way off, toward the heart of the storm. It builds like a crescendo, growing louder and louder until it consumes all of the air around me. The fist of Neptune strikes, and with its blast the raft is shot to a staggering halt. It squawks and screams, and then there is peace, as though we have passed into the realm of the afterlife where we cannot be further tortured.

Quickly I yank open the observation port and stick my head out.

Solo's

jib is still snapping and her rudder clapping, but I am drifting away. Her electrics have fused together and the strobe light on the top of her mast blinks good-by to me. I watch for a long time as the flashes of light become visible less often, knowing it is the last I will see of her, feeling as if I have lost a friend and a part of myself. An occasional flash appears, and then nothing. She is lost in the raging sea.

I pull up the line that had tied me to my friend, my hope for food and water and clothing. The rope is in one piece. Perhaps the loop I had tied in the mainsheet broke during the last shock. Or the knot; perhaps it was the knot. The vibration and surging might have shaken it loose. Or I may have made a mistake in tying it. I have tied thousands of bowlines; it is a process as familiar as turning a key. Still ... No matter now. No regrets. I simply wonder if this has saved me. Did my tiny rubber home escape just before it was torn to pieces? Will being set adrift kill me in the end?

Somewhat relieved from the constant assault on the raft, I chide myself in a Humphrey Bogart fashion. Well, you're on your own now, kid. Mingled with the relief is fright, pain, remorse, apprehension, hope, and hopelessness. My feelings are bundled up in a massive ball of inseparable confusion, devouring me as a black hole gobbles up light. I still ache with cold, and now my body is shot through with pain from wounds that I've not noticed before. I feel so vulnerable. There are no backup systems remaining, no place to bail out to, no more second chances. Mentally and physically, I feel as if all of the protection has been peeled away from my nerves and they lie completely exposed.

M

Y RAFT AND I

slide up and down breaking waves throughout the night. I have set the sea anchorâa piece of cloth that acts like a parachute in the water, slowing our descent and preventing us from capsizing. A wave breaks under us and throws the raft up until it rests on its front edge like a top. Gallons of black brine flood the raft. As I dangle from the handlines, hammering crests batter me through the raft's thin bottom. Just before we make a complete flip, the sea anchor comes up taut and jerks the raft back down. Newly scooped seawater rushes back upon me like a cold spring stream.

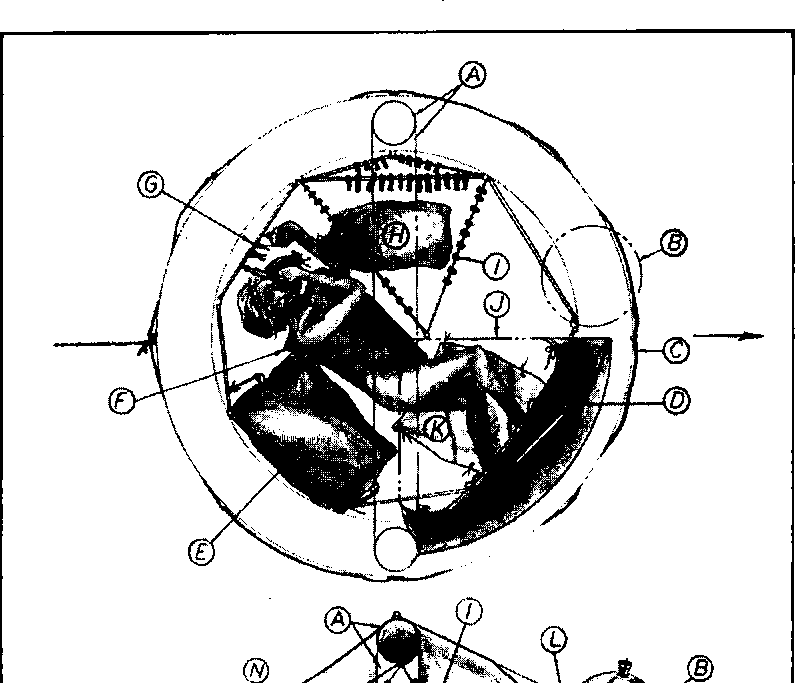

My life raft is a standard Avon six-man model composed of two multisegmented inner tubes, one stacked on the other. The inside diameter is about five feet, six inches. Before the start of the Mini-Transat, the race committee inspected

Solo

and was surprised to find such a large raft. "Have you ever gotten into a four-man raft?" I asked them. I had. I once blew one up and two friends joined me inside. We were literally on top of one another, our knees overlapping. Survival for more than a few days, with the raft loaded to legal capacity, would be questionable, and torturous at best. I figured a six-man raft might suffice for a crew of two for a moderate to long-term voyage.

Spanning the top tube is a semicircular arch tube that supports the tentlike canopy. One quarter of the canopy is loose to form the entry opening. The only spot with full sitting headroom is directly in the center of the raft. I can wedge myself against the outside perimeter so my head pushes up into the canopy, or slouch down to brace myself across the bottom. The raft is constructed of black dacron-reinforced rubber material, which is glued together. Extra strips of this material are laid over the seams. I'm only too aware of the many cases where life rafts have been torn apart. I memorize each cobweb of glue where the tubes join and continually watch for any sign of tearing or stretching. The top and arch tube make up one inflation chamber and the bottom tube another. The safety valves spill any pressure in excess of two and one-half pounds per square inch. It is impossible to inflate the tubes by mouth; an air pump must be used. The entire structure is constantly undulating like an uneasy, coiled snake.

Two views of Rubber Ducky III. In the profile view I am shown grasping the air pump, which is plugged into one of the valves. Rubber Ducky III has an upper and arch-tube inflation chamber and a bottom-tube chamber. The wind is from the left in these views, pushing Ducky to the right. (A) arch tube: supports the canopy; (B) solar still: bridled in place. The distillate drainage tube and bag hang down and under the raft; (C) exterior handline: runs all around the outside of the raft; (D) spray skirt or bib: across the entry opening, keeps some waves out and provides a shelf for the spear gun; (E) equipment bag: salvaged from Solo, contains the bulk of gear; (F) cushion: made of two-inch-thick closed-cell foam, which does not absorb water. This helps to cushion blows from sharks and fish under the raft; (G) interior handline: serves as an anchor for all the equipment. Fish are strung up between the anchor points. In the plan view the arrow points to the water bottle, sheath knife, and short pieces of line in position for instantaneous access; (H) raft equipment bag: supplied with the raft when purchased. It contains standard equipment such as the air pump and it is secured to an anchor point on the floor; (I) clothesline: to hang fish in the "butcher shop." Strung between the handline anchor points and up to the canopy arch tube; (J) entry opening (shown by the phantom line): kept on the forward right quarter of the raft away from the wind and approaching waves; (K) sail cloth: salvaged from Solo, folded and tied. Helps to cushion fish blows and to protect the raft from damage from the spear tip when fish are landed; (L) Tupperware box: wedged in the solar still bridle where it catches rain. Later on it will be positioned on the top of the canopy arch tube on its own bridle, and then inside under the leaky observation port; (M) EPIRB (Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacon): sends a signal on two frequencies monitored by commercial flights; (N) observation port: leaks badly and must be tied up since it is on the windward side. Eventually a water collection cape will drain through this opening into the Tupperware container; (O) painter to the man-overboard pole: trails astern, and serves as speedometer. It also keeps the raft aligned properly and prevents capsize. The pole increases my visibility. The line gives a good surface for the growth of barnacles, on which I and the triggerfish feed; (P) gas cylinder: inflated Rubber Ducky. Its vulnerable position is always a worry; (Q) ballast pocket: four pockets on the bottom fill with water to prevent capsizes; (R) sagging floor: typical where any weight pushes down. Water pressure otherwise forces the floor to arch upward slightly. The bumps pushing downward make good targets for fish, such as the dorado shown aiming for my left foot.