Afterlands (24 page)

Mar. 10?11?—Calm shattered by Gale. Raft groans as tho’ to go to pieces yet I feel myself near whole. Am now but little distracted by her, whether charms or defects, being wholely concerned with survival of Party. & God being unwilling it appears, to let us off without farther Trial. But surely Hardships some times are sent to rescue us from baser things? So be it. She thinks now but little of K I believe for when I told of my discovery he was prob. main Thief she appeared v. disturbed. Well he is Trouble & this may help her to avoid him

.

The prospect of execution doesn’t so much concentrate the mind as make it scan inward for any escape, any distraction. The uproar outside is like the sound of immense jaws crunching something inedible. Kruger keeps returning to a certain windless evening, a sharp V of red-breasted geese appearing, with joyful cries, above Danzig Harbour.

Was ist Trumpf?

Lundquist speaks in a falsetto bass, a boy with something to prove to men, as the floe tilts and pitches like a large raft in an ocean storm—exactly what it is.

Kreuz, ja?

He, Kruger, Herron, and Anthing, shawled in pelts, sit on the bed-ledge playing euchre in a silence better fit for solitaire. Two a.m. Jamka, Bavarian by birth, has been kneeling on the canvas floor for hours chanting monotone Ave Marias. He’s refusing to wear his boots. His feet are blackening like a mummy’s. For the first hour or so Kruger was moved by the chanting, returned to boyhood and his wonderfully fat mother who prayed mainly for her husband to glimpse the Light and the Lamb beyond his free thinking. Count Meyer is murmuring in his sleep. In Lindermann’s bag, Lindermann and Madsen lie cramped together, unmoving, all pretence abandoned. Beside them Jackson in his fingerless gloves holds the lamp and gazes down at it, face skulled by the underlight; what if the ice should open under them and their lamp slip through, into the sea?

We dasn’t lose this lamp, he repeats.

Well

that

was a loud one, lads! Herron’s stumpy fingers tremble as they hold his cards; the worse things get, the more he chatters. Like a broadside at Trafalgar, he says. Lord help us.

After this hand, I go to check on the others, Kruger says.

I think I know what concerns you, Anthing says, his features bland, illegible as a valet’s.

That it will split between us and her! Herron babbles—then he adds quickly, I’m sorry, Kru.

It’s natural enough, Anthing says with a neutral shrug.

Kruger eyes him narrowly over the cards.

Swam in the Hiwassee when I was a boy, Jackson says. I always could swim.

Nunc, et in hora mortis nostrae …

Water there, it’s like demerara cooked in butter—just that colour. And just as warm.

Well, Matty, the good hands are all to you tonight, aren’t they?

I can swim too, Kruger says absently, tossing his cards onto the pile.

Bitte … kommst du hier!

It’s Meyer, ogling Kruger with one open eye. How hard that makes it to ignore his plea, though Kruger would prefer to remain where he is—gaping up at a chevron of red-breasted geese, their stained-glass panes of rich colour, beating low over the harbour, north toward the Arctic, as he emerges for the first time from a dockside brothel, now apparently a man.

Ja, Graf Meyer?

He crouches beside Meyer’s private ledge. Under his knee the floe sways and shudders and his quivering muscles accent the effect.

I have been meaning to let you in on a little secret, Herr Krüger.

The eye, all pupil, stares unfocused. Kruger nods reluctantly.

All this talk of spies, Herr Krüger …

Ja

, I understand it to be nonsense, Graf Meyer.

Ah, but to the contrary!

A pause while Meyer fights for breath. That one staring eye—it’s like being addressed by a determined octopus. Kruger has to incline an ear to catch Meyer’s phlegmy whisper: Because we

are

all secret agents of the Kaiser, you see. All this was arranged, by Bismarck! We

are

spies!

Anthing is peering over sidelong, but Kruger doubts he can hear over the chaos of the ice. Lundquist is quietly retching into the pemmican tin he keeps handy tonight. In a patient, almost parental tone Kruger says,

Herr Graf

, we are

Ausgewanderte—

emigrants, hired because Americans didn’t want the job. They’re all going west, American men. Wise of them, I now feel.

But Doktor Bessels and I—we

arranged

for Germans to be hired! We believed we could count on such men, to help plant our flag at the Pole! We even armed them, after Hall’s death.

Sleep now, Kruger urges.

You drooling lunatic

.

We and America will be the Great Powers of the century to come! We must begin now …

He trails off. His other eye opens wide and also regards Kruger, but, unlike the first eye, it doesn’t seem to recognize him. In fact, it looks frankly hostile. The first eye remains almost affectionate. Profiting by this confusion, Kruger retreats to his sleeping bag and slips his parka on. If there’s any truth to the Count’s fevered ramblings, it would mean that Captain Hall, in his own delirium, may have been right to loudly accuse Bessels and Meyer of poisoning him, just before he died. But who can say? It would be very like the Count now to imagine himself as Bismarck’s right-hand man. Out here in such extremity you would expect everything and everyone to be stripped down to a hard, pure essence—all lies laid bare—yet with every hour the Truth grows more uncertain and unstable.

He crawls into the dark tunnel. Something is padding, panting its way in from the mouth of the tunnel and he and this other come face to face, as if deep underground. It’s Tyson, his laboured breaths smelling like copper pennies.

I’ve come to see how you men are doing.

Sir. I also was coming out to see how the rest are.

Well—Tyson’s voice bristles slightly, as if upstaged somehow, or challenged—we are all fine. The natives, of course, can take care of themselves.

Of course, Kruger says. And neither man moves. Clearly enough Tyson doesn’t want him to visit Tukulito. It has become clear to Kruger that every white man on the floe believes them to be lovers, and that they all hate him a little for that. Even Herron, perhaps. Hated for a love that he seems to have no chance, or right, to consummate! Like burrowing, brute creatures, minds stalled with terror and fatigue, the two men remain unmoving for some time.

March 12

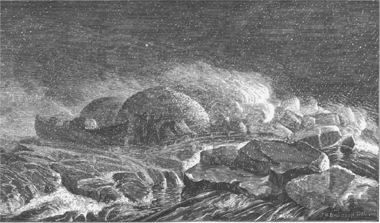

. Another twenty-four hours of care, watching, anxiety, and great peril. The gale has been terrible. For sixty hours, amidst this fearful turmoil of the elements, with our foundations breaking up beneath us, we could not see ten yards around; but this morning at last the wind has abated, the snow has ceased to fall, and the terrible drift stopped. We can now look around and see the position we are in. In a vessel, after such a storm as this, the first work, with returning light, would be to clear the decks and set about repairing damages. But how shall we repair our shattered ice-craft? We can look around and take account of loss and damage, but we can do nothing toward making it more sea-worthy.

We see a great change in the condition of the ice; the “floes” have become a “pack,” and great blocks of ice, of all shapes and sizes, are piled and jammed together in every imaginable position. On my last extended walk before this storm, the large floes had appeared to extend for many miles; they are now all broken up like ours, and the pieces heaped over each other in most astonishing disorder. Moreover, we are still surrounded by the icebergs which have drifted with us all winter—though of course they are now much closer on all sides, and hence seem higher, our floe being so reduced. Though they are a peril to us, and may well end by destroying us, yet their familiar presence is also a strange comfort.

With the winds more moderate, we recommenced shooting. Seals are scarce, but, there being open water around us and between the cracks, we can now shoot all we see. Indeed, we can stand in our own hut door and shoot them, for our floe is

so

diminished that it is only forty paces to the water. Today Joe shot two, Hans one, and the former thief Kruger, one as well. Then, espying another oogjook, not as large as our first kill, but still very considerable, I asked to borrow Hans’s rifle, after which I crept as close to the animal as I dared. My first shot went true, thank God; and as we dragged the oogjook onto our floe, the sun appeared for the first time in days, as if further to encourage us.

And so it seems that one danger—that of starvation—may be receding even while another, more urgent one, closes in; but now that we are no longer “a house divided,” the odds do not seem so unbeatable. The sun will enter the first point of Aries in just a few days, and be on his upward course. Spring is here, according to the astronomers; but oh how I wish that another month were passed!

It is mild enough in the sunshine in the lee of the hut that she can butcher the huge carcass outdoors. Though the noon sun is not high the atmosphere is alive with light, as if charged with dazzling particles—the sun’s rays reflecting off the ice and the hut and the slow, dignified armada of icebergs convoying them south. This light is inebriating. So is the sight and the smell of fresh meat. With her woman’s knife she flenses the body, its grey-furred “blanket” heavy with fat peeling off smoothly as a ripe peach skin. Beside her Kruger is haunched down, holding the cool blanket clear of her gory hands while she cuts deeper, in toward the spine, pivoting her wrist back and forth, her braids swinging. It’s only the two of them. The recent abundance has made everyone more trusting about food. Heat radiates from the cleft flesh as if from a bank of raked coals; the blanket has retained the inner heat for hours. There’s a raw smell. The scalloping incisions of her red-daubed blade—a half-moon of steel with a toggle-shaped handle.

What is the word in your language, Hannah, for this knife you use?

It is called

ulu

, Mr Kruger.

He nods slowly. I’m surprised that without a whetstone you have kept it so sharp. But I suppose that cutting ice with it might help. Once I saw you doing that, at the pond.

She doesn’t look up from her work. She ducks her bare head nearer to the carcass, into the shadow of the blanket, which Kruger lifts higher as she cuts inward. He shifts closer to her, wanting to keep his voice down.

But I don’t suppose you often use it that way?

As you know, sir, my husband has tools better suited for such work.

There’s a squelchy, sucking noise as she swivels the crescent blade side to side. Her shiny hair is parted above the nape, tight-spread, tapering to the drooping braids. The furrow of scalp is oddly red.

I believe he had taken his snow knife with him that day, the day you saw me.

Yes.

Please pull the blanket farther back, if you would. I am cutting over the spine now.

His wasted shoulder muscles burn as the blanket grows heavier. He has to stand to hold it up. His hip bone presses into her working shoulder, through the parka. Somehow, with no appreciable movement other than those of her cutting, she recoils from him slightly.

He eyes the moving blade.

It took me until now, watching you work, to know what made those marks. In the ice.

Be careful, sir, I have to cut over this way.

A glottal sound and a rich stink as more of the blanket works free. The animal is still on its side. She leans, reaches under the blanket that Kruger holds high, his arms now trembling, and frees the skin over the abdomen. Then she digs lower.

I owe you my apologies, he says, looking down at her back, the loose, jiggling hood. For taking from your cache. I believed it was Meyer’s—or maybe the lieutenant’s. (He doesn’t add what now occurs to him: that in his hunger and aloneness, he might have raided the cache even if he had known it was hers.)

In that case, she says calmly, you don’t know the lieutenant very well.

I begin to think I don’t know anyone very well—yourself included. Still, I’m sure that your reasons for hoarding were good. You must have realized the men intended to leave you nothing.

Please move to the other side of him now.

Yes. And Hannah, I know—Tukulito—I know how much you love your daughter. I did try to give back something to the child, you know. Some of what little I stole.

He now stands across from her, the blanket held high, like a man allowing a wife some modesty on a bathing-beach as she changes. Her lowered, crimped brow is reddening, upward to the hairline. It could be from the work; from anger; from shame. She’s freeing the skin and blubber from over the retracted genitals. Kruger looks away. The animal’s right eye, dark and soulful as a spaniel’s, meets his.

Yes, she says, I thought it was you. Otherwise I would have moved it. Her flat sun-shaped face is squinting up, the direct light hardening her look so it’s impossible to know whether her sternness is real or just an effect of the brightness. Still, she allowed him to eat from her cache—which she made and kept against her own people’s taboos—and although in the end she could have let him shoulder the blame for it, she must have taken the risk of returning the supplies herself, thus helping him clear his name, at least in the crewhut. If love is just deep respect fused with desire, then that’s what absorbs him now. Bellyfuls of meat for days have revived his other hungers. Even the other men have begun to look almost fetching. At the same time they look truly awful. Everybody looks awful. Only Tukulito, he thinks, has retained something of her inward and outward grace.