Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (9 page)

Read Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk Online

Authors: Peter L. Bernstein

Diophantus lived to be 84 years old.

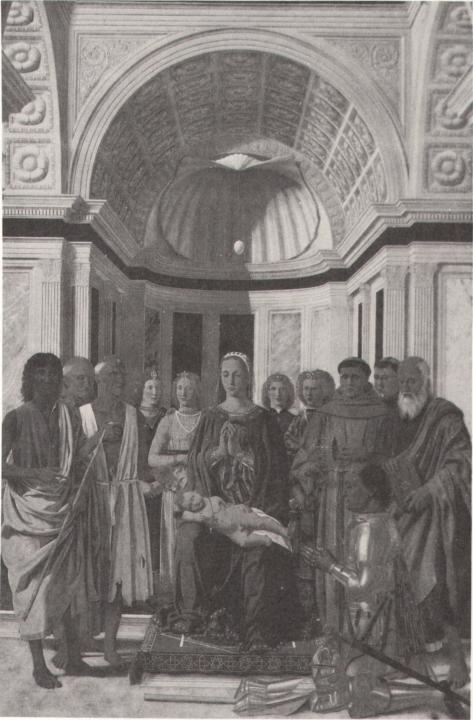

iero della Francesca, who painted the picture of the Virgin that

iero della Francesca, who painted the picture of the Virgin that

appears on the following page ("The Brera Madonna"), lived

from about 1420 to 1492, more than two hundred years after

Fibonacci. His dates place him at the center of the Italian Renaissance,

and his work epitomizes the break between the new spirit of the fifteenth century and the spirit of the Middle Ages.

Della Francesca's figures, even that of the Virgin herself, represent

human beings. They have no halos, they stand solidly on the ground,

they are portraits of individuals, and they occupy their own threedimensional space. Although they are presumably there to receive the

Virgin and the Christ Child, most of them seem to be directing their

attention to other matters. The Gothic use of shadows in architectural

space to create mystery has disappeared; here the shadows serve to

emphasize the weight of the structure and the delineation of space that

frames the figures.

The egg seems to be hanging over the Virgin's head. More careful

study of the painting suggests some uncertainty as to exactly where this

heavenly symbol of fertility does hang. And why are these earthly, if

pious, men and women so unaware of the strange phenomenon that has

appeared above them?

Madonna of Duke Federico II di Montefeltro. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy.

(Reproduction courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, NY.)

Greek philosophy has been turned upside down. Now the mystery

is in the heavens. On earth, men and women are free-standing human

beings. These people respect representations of divinity but are by no

means subservient to it-a message that appears over and over again in

the art of the Renaissance. Donatello's charming statue of David was

among the first male nude sculptures created since the days of classical

Greece and Rome; the great poet-hero of the Old Testament stands

confidently before us, unashamed of his pre-adolescent body, Goliath's

head at his feet. Brunelleschi's great dome in Florence and the cathedral, with its clearly defined mass and unadorned interior, proclaims

that religion has literally been brought down to earth.

The Renaissance was a time of discovery. Columbus set sail in the

year Piero died; not long afterward, Copernicus revolutionized humanity's view of the heavens themselves. Copernicus's achievements

required a high level of mathematical skill, and during the sixteenth

century advances in mathematics were swift and exciting, especially in

Italy. Following the introduction of printing from movable type around

1450, many of the classics in mathematics were translated into Italian

and published either in Latin or in the vernacular. Mathematicians

engaged in spirited public debates over solutions to complex algebraic

equations while the crowds cheered on their favorites.

The stimulus for much of this interest dates from 1494, with the

publication of a remarkable book written by a Franciscan monk named

Luca Paccioli.' Paccioli was born about 1445, in Piero della Francesca's

hometown of Borgo San Sepulcro. Although Paccioli's family urged

the boy to prepare for a career in business, Piero taught him writing,

art, and history and urged him to make use of the famous library at the

nearby Court of Urbino. There Paccioli's studies laid the foundation

for his subsequent fame as a mathematician.

At the age of twenty, Paccioli obtained a position in Venice as tutor

to the sons of a rich merchant. He attended public lectures in philosophy and theology and studied mathematics with a private tutor. An apt

student, he wrote his first published work in mathematics while in

Venice. His Uncle Benedetto, a military officer stationed in Venice,

taught Paccioli about architecture as well as military affairs.

In 1470, Paccioli moved to Rome to continue his studies and at the

age of 27 he became a Franciscan monk. He continued to move about,

however. He taught mathematics in Perugia, Rome, Naples, Pisa, and Venice before settling down as professor of mathematics in Milan in

1496. Ten years earlier, he had received the title of magister, equivalent

to a doctorate.

Paccioli's masterwork, Summa de arithmetic, geometria et proportionalita'

(most serious academic works were still being written in Latin), appeared

in 1494. Written in praise of the "very great abstraction and subtlety of

mathematics," the Summa acknowledges Paccioli's debt to Fibonacci's

Liber Abaci, written nearly three hundred years earlier. The Summa sets

out the basic principles of algebra and contains multiplication tables all

the way up to 60 x 60-a useful feature at a time when printing was

spreading the use of the new numbering system.

One of the book's most durable contributions was its presentation of

double-entry bookkeeping. This was not Paccioli's invention, though

his treatment of it was the most extensive to date. The notion of double-entry bookkeeping was apparent in Fibonacci's Liber Abaci and had

shown up in a book published about 1305 by the London branch of an

Italian firm. Whatever its source, this revolutionary innovation in

accounting methods had significant economic consequences, comparable to the discovery of the steam engine three hundred years later.

While in Milan, Paccioli met Leonardo da Vinci, who became a

close friend. Paccioli was enormously impressed with Leonardo's talents

and commented on his "invaluable work on spatial motion, percussion,

weight and all forces."2 They must have had much in common, for

Paccioli was interested in the interrelationships between mathematics

and art. He once observed that "if you say that music satisfies hearing,

one of the natural senses ... [perspective] will do so for sight, which is

so much more worthy in that it is the first door of the intellect."

Leonardo had known little about mathematics before meeting

Paccioli, though he had an intuitive sense of proportion and geometry.

His notebooks are full of drawings made with a straight-edge and a compass, but Paccioli encouraged him to master the concepts he been using

intuitively. Martin Kemp, one of Leonardo's biographers, claims that

Paccioli "provided the stimulus for a sudden transformation in Leonardo's

mathematical ambitions, effecting a reorientation in Leonardo's interest in

a way which no other contemporary thinker accomplished." Leonardo in

turn supplied complex drawings for Paccioli's other great work, De Divine

Proportione, which appeared in two handsome manuscripts in 1498. The

printed edition came out in 1509.

Leonardo owned a copy of the Summa and must have studied it with

great care. His notebooks record repeated attempts to understand multiples and fractions as an aid to his use of proportion. At one point, he

admonishes himself to "learn the multiplication of the roots from master

Luca." Today, Leonardo would barely squeak by in a third-grade arithmetic class.

The fact that a Renaissance genius like da Vinci had so much difficulty with elementary arithmetic is a revealing commentary on the state

of mathematical understanding at the end of the fifteenth century. How

did mathematicians find their way from here to the first steps of a system to measuring risk and controlling it?