Alex's Wake (18 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

I don't know I am asking too much, if I want to know what the fate of the 900 passengers of the âSt Louis'âbetween them my motherâwill be. I got informations like that: Friday, greater N.Y. Committee: 4:30 PM: âWe are still in conference with

Cuba. Everything is in our hand.' 5 minutes later I called your Committee: âThere are no conferences with Cuba any more and the boat will not be stopped because there is no hope for other negotiations.'

In the last 24 hours no news at all. I even don't know anymore what kind of a message I shall give my mother to console her. Shall I tell her that you are in conference still with Cuba? Or that there are no conferences at all any more? That the boat will go to Europe back now? That they should be prepared for the worst?

I know you will understand the torture of that uncertainty now spread out over weeks even you have no mother or relativs on bord. And if you understand, you will give a statement to the unhappy on bord and their relativs what they are going to exspect now after all those terrible days.

At 11:30 p.m. on Tuesday, June 6, the day President Bru announced the termination of his government's involvement with the refugees, Captain Gustav Schroeder received a terse cable from Claus-Gottfried Holthusen, director of the Hamburg-America Line. It read simply, “Return Hamburg Immediately.” At 11:40, from a location about twelve miles off Jacksonville, Florida, Captain Schroeder ordered his helmsman Heinz Kritsch to bring the ship onto a course of east by northeast. The

St. Louis

was headed back to Germany.

The passengers' committee, led by Josef Joseph, decided that the time had finally come to appeal directly to President Roosevelt for permission to land somewhere in the United States. They sent a telegram to the White House pleading, “Help them, Mr. President, the 900 passengers, of which more than 400 are women and children.”

The text of the telegram was printed in the June 7 edition of the

New York Times

. That paper and a number of other news outlets had been reporting the tale of the unhappy refugees aboard the

St. Louis

for more than a week, galvanizing American public opinion. There were marches in the streets of New York, Washington, Chicago, and Atlantic City, the demonstrators calling on the Cuban government to allow the

St. Louis

passengers to disembark in Havana. Walter Winchell, broadcasting his radio program to “Mr. and Mrs. America and all the ships at sea,” insisted that the root of the issue was the root of all evil: not the failure to touch Cuban hearts but the “failure of touching Cuban palms. And we don't mean trees.” Another telegram arrived at the White House addressed to President Roosevelt, this one from a number of Hollywood actors, among them Miriam Hopkins and Edward G. Robinson. It read, “In name of humanity urge you bring all possible influence on Cuban authorities to radio return of German liner St. Louis, now at sea returning over nine hundred refugees to imprisonment and death in Nazi Germany Urge Cuba give at least temporary shelter until another refuge can be found in democratic country.”

Editorials in the

Washington Post

, the

Miami Herald

, the

Philadelphia Record

, and the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

all decried the treatment of the Wandering Jews of the Caribbean and stated forthrightly variants of the sentiment “something must be done.” On June 8, in an editorial titled simply “Refugee Ship,” The

New York Times

declared, “The saddest ship afloat today, the Hamburg-American liner St. Louis, with 900 Jewish refugees aboard, is steaming back toward Germany after a tragic week of frustration at Havana and off the coast of Florida. No plague ship ever received a sorrier welcome. At Havana the St. Louis's decks became a stage for human misery. The refugees could see the shimmering towers of Miami rising from the sea, but for them they were only the battlements of another forbidden city. Germany, with all the hospitality of its concentration camps, will welcome these unfortunates. The St. Louis will soon be home with its cargo of despair.”

On June 9, the

Times

editorialized, “Attempts to trace responsibility for the plight of the refugees on board the Hamburg-American liner St. Louis lead into dark byways of human hard-heartedness. It is difficult to imagine the bitterness of exile when it takes place over a far-away frontier. Helpless families driven from their homes to a barren island in the Danube, thrust over the Polish frontier, escaping in terror of their lives to Switzerland or France, are hard for us in a free country to visualize. But these exiles floated by our own shores. We can only hope that some hearts will soften somewhere and some refuge be found. The cruise of the St. Louis cries to high heaven of man's inhumanity to man.”

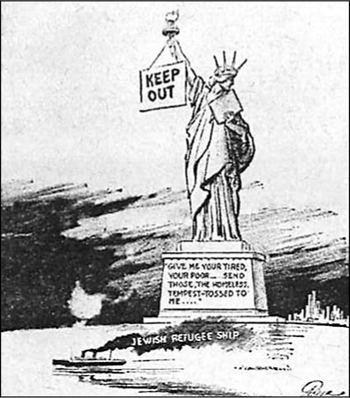

Fred Packer's cartoon from the June 6, 1939, edition of the

New York Daily Mirror

. It expressed a sentiment shared by many editorialists and American citizens, though not enough to influence the Roosevelt Administration to offer the ship safe harbor

.

One of the most striking images was a political cartoon by Fred Packer, a future Pulitzer Prize winner, that appeared in the

New York Daily Mirror

. Under the headline “Ashamed!,” the Statue of Liberty stands with eyes averted as a boat labeled “Jewish Refugee Ship” steams past. Hanging from her upraised right arm, the arm bearing the torch, is a sign that reads, “Keep Out.”

But for all those general expressions of support for the

St. Louis

passengers, few people explicitly demanded their admission to the United States. The

Post-Dispatch

editorial made a vague reference to America's “broad expanses of unoccupied or sparsely settled territory” where, presumably, these wretched wanderers could be placed. Other papers declared that once this particular ship was allowed to circumvent the letter of the immigration law, a “dangerous precedent” would be set and other illegal vessels would soon be steaming toward American ports. Even the

Times

never came right out and called for a policy that would allow the

St. Louis

to sail past Miss Liberty and tie up at Ellis Island.

Her “golden door” remained firmly closed to these particular “homeless, tempest-tossed” exiles.

Several interlocked reasons explain why America failed to welcome the refugees to their own shores. The Immigration Act of 1924, still very much on the books, set rigid quotas that limited the number of people who could enter the United States each year. For 1939, the quota from Germany and Austria was 27,370. Adding nearly a thousand more, all at once, would mean that an equal number of German Jews who had already applied for visas would have to be turned away.

Then there was the matter of American public opinion. Newspapers from coast to coast had been documenting the increasing savagery of the Nazis' treatment of the Jewsâthe events of

Kristallnacht

had been front-page news in dozens of papersâand by and large the American people were sympathetic. But anti-Semitism was by no means restricted to Europe. In 1938, the highly respected Elmo Roper polling agency asked a sampling of the American public, “What kinds of people do you object to?” Fourteen percent of the respondents answered “uncultured, unrefined, dumb people”; 27 percent answered “noisy, cheap, boisterous, loud people”; and 35 percent, the highest number, answered simply, “Jews.” The following year, another Roper poll revealed that 53 percent of the Americans queried thought that Jews were “different” from other people and thus should be subject to “restrictions” in their business and social lives. That same poll found that only 39 percent of the respondents believed that Jews should be treated the same as everyone else and that 10 percent of those polled thought that Jews should be deported. Despite their general compassion for the plight of the

St. Louis

refugees, most Americans did not want the United States to become a haven for European Jews. According to a poll taken in the spring of 1939 by

Fortune

magazine, 83 percent of the American people opposed relaxing restrictions on immigration.

Few politicians, including the nation's First Politician, were willing to discount such majority opinion. An attempt to admit twenty thousand Jewish children from Germany, the Wagner-Rogers Bill of 1939, had died in committee. President Roosevelt, already gearing up his campaign for an unprecedented third term and unwilling to

become mired in the immigration issue, had spoken not a word on Wagner-Rogers. In response to the telegrams he'd received from the

St. Louis

passengers' committee and elsewhere, President Roosevelt remained silent.

Eleanor Roosevelt, thought by many Americans to be more compassionate than her husband, also received many pleas on behalf of the

St. Louis

voyagers. On June 8, an eleven-year-old girl named Dee Nye wrote to Mrs. Roosevelt, “Mother of our Country, I am so sad the Jewish people have to suffer so. Please let them land in America. It hurts me so that I would give them my little bed if it was the last thing I had because I am an American let us Americans not send them back to that slater house. We have three rooms that we do not use. Mother would be glad to let someone have them. Sure our Country will find a place for them, so they may rest in peace.”

Like the passengers' committee and Edward G. Robinson, Dee Nye never received an answer. The United States of America would not permit the

SS St. Louis

to land at any of its ports.

One last possibility in the Western Hemisphere remained. Ships sailing the transatlantic crossing for HAPAG had put in at Halifax, Nova Scotia, for decades. With the

St. Louis

now two days out from Halifax, Captain Schroeder contacted Canadian authorities for permission to enter Halifax Harbor. But perhaps fearing repercussions from its powerful neighbor to the south, the government of Prime Minister William Mackenzie King added Canada to the list of nations that offered no succor to the

St. Louis

.

Joseph Goebbels seized on the news as further proof that the world shared the Nazis' opinion of what they called a “criminal race.” “Since no one will accept the shabby Jews on the

St. Louis

,” the Propaganda Ministry declared, “we will have to take them back and support them.”

It took little imagination to conclude that Nazi “support” more than likely meant sending the passengers to the camps, and fear on board the ship grew to crisis proportions. A band of passengers attempted mutiny, overpowering the crew and temporarily seizing control of the engine room. The uprising was quickly contained, but the refugees had managed to convey their desperation to the outside world, which had begun

to take a markedly increased interest in their fate. The

Washington Post

ran a story headlined, “200 Jews Aboard St. Louis Decide on Mass Suicide.” It read, in part:

Driven from every American port, like a pestiferous cargo, the 925 [sic] Jews on the St. Louis are prepared to face a self-inflicted death rather than experience the horrors of German concentration camps, according to wireless dispatches received by friends and relatives of the refugees, as the liner definitely steered a course for Hamburg.

Turned back by Cuba, unwanted by Mexico, the refugees saw their last hope of a new life vanish when they learned that President Roosevelt had refused to consider all appeals made directly to him. With blank despair staring them in the face, 200 of these modern pariahs have now decided to make their supreme protest against the civilization in which their lot has been cast by sacrificing their lives before the St. Louis comes within sight of Germany's shores.

The suicide pact has been made in calm consciousness that the sacrifice might draw world attention to the outrage against humanity committed in their regard. The men and women who have taken it are persons of culture and the high positions they formerly occupied in Germany are a guaranty of their high-mindedness.

The cultured passengers had only been able to communicate with their friends and families on land because they had pawned such items as jewelry, cameras, and clothing with members of the ship's crew in order to obtain the money required to send their unhappy telegrams.

For his part, Herbert Karliner remembers that up to three hundred people on board the

St. Louis

were prepared to jump overboard rather than risk setting foot once more on German soil. He also recalls that the mood of the return voyage to Europe was vastly different from that on the initial crossing; there were no dances, no movies, no games. The menus, which had been individually offered for each meal and

included a number of choices, were now presented on a single mimeographed sheet each day, with no options available. Hope had largely been replaced by despair.