Alex's Wake (50 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

“The story is of two Buddhist monks, an older man and a younger man, who are traveling many miles on foot to their monastery. It has been raining heavily and when they come to the bank of a river, they find that the bridge has been washed away. Standing on the bank is a

young woman. âPlease, sirs,' she says to the monks, âI need to get to the other side of the river to feed my children their evening meal. Will you be so kind as to carry me across?' The younger monk begins to explain that their order does not allow them to come into physical contact with women, but the older monk stoops, gestures to his companion to do the same, and then invites the woman to climb onto their shoulders. She does so, and the two monks then wade across the river, transporting her safely to the other side. She jumps to the ground, thanks them profusely, and the two monks continue their journey.

“That evening, as the shadows are beginning to lengthen, the younger monk says, âMaster, I continue to be somewhat troubled by our encounter along the river bank. We have made certain holy vows, and one of them is that we do not touch women under any circumstances. And yet you broke your vow and caused me to break mine. Why, Master?'

“The older monk stops walking and, turning to his young companion with a smile filled with kindness, says, âI set that woman down upon the river bank many hours ago now. Why are you still carrying her?'”

I pause and see Roland nod his head slowly as he reaches for Hilu's hand.

“I have carried the burden of guilt and anger and sorrow for many years now,” I say. “It may have served a purpose, but this evening, in this place, before you kind people, I vow to set it down. Or at least, to try my best.”

I sit then, closing my eyes. Amy kisses the back of my neck, Deborah grips one of my hands and Steven the other. Loud applause fills the living room of my grandfather's house.

We then file out the front door into a misty evening. Carsten appears at my side. He is smiling broadly with the clear evidence of tears in his eyes. “Thank you,” he whispers. “Thank you so much for your beautiful words. You have given me permission to set down my burden also.”

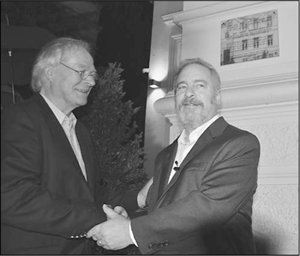

At a signal from Monica, Carsten and I both grasp a long piece of string that is connected to the blue cloth on the front of the house. We pull gently and the cloth falls away to reveal the memorial plaque. The crowd cheers and Carsten and I shake hands.

Carsten Meyerbohlen and I shake hands moments after the unveiling of the memorial plaque at 34 Gartenstrasse

.

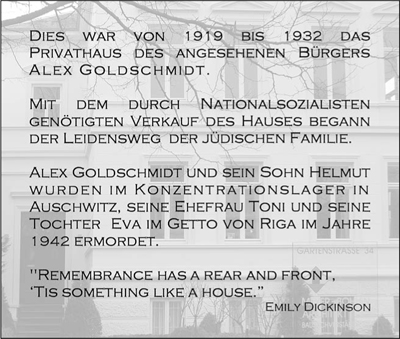

The plexiglass plaque has been designed by Carsten himself. Against an image of the house in winter, there appear the words, in German:

From 1919 until 1932 this was the private house of the respected citizen Alex Goldschmidt. With the forced sale of this house to the National Socialists, the sorrowful journey of this Jewish family began. Alex Goldschmidt and his son Helmut in the Auschwitz concentration camp, and his wife Toni and daughter Eva in the Riga ghetto, were murdered in 1942.

Below that, in English, are the lines from the poem by Emily Dickinson that I suggested for the plaque:

Remembrance has a rear and front,

'Tis something like a house.

Amy hugs and kisses me. She, who has been with me every step of this long journey, is crying. Then Deborah appears, sobbing, and I hold

her tightly as she tries to speak. “They had so much,” she manages finally. “Oh, and they lost so much.” And then my newfound cousin Steven, whom I realize in this moment I love like family, is also by my side, also in tears, and we all wrap our arms around one another, sharing our bottomless sorrow and our heady triumph at having survived the evil efforts of our enemies and our pleasure at this written proof of our family's existence on the wall above our heads and our great joy at having come so far to find one another.

Journeys end in lovers meeting.

W

E REPAIR TO THE

N

EIDHARDTS

'

COMFORTABLE HOME

âAmy, Steven, Helen, Deborah, Farschid, Dietgard, Carsten, Monica, and about a dozen other people who are friends of the Neidhardts or the Meyerbohlens. Hilu has prepared a delicious stew and there is amply flowing beer, wine, and mineral water. There is music and laughter and animated conversation. Everyone seems to think that the evening has been a roaring success, and everyone's spirits are high. It feels like a party, like an exuberant gathering after a solemn occasion. I suddenly decide, with apologies to the Irish, that this is a wake. Alex's wake.

I stand, a bit unsteadily, and find a spoon to clink against my glass, commanding the room's attention. “Pardon this brief interruption,” I say, perhaps a few decibels louder than necessary. “I would like to propose a toast. There are many people who warrant toasting tonight, and I'm the right man to do it, since I'm more than a little toasted myself.” I laugh, and if my laughter lasts a bit longer than it should, no one seems to mind.

“To my grandfather!” I exclaim, lifting my glass high. “To Alex!” And from all corners of the room comes the hearty reply, “To Alex!”

I notice Pastor Dietgard sitting in a corner next to an empty chair and, a trifle straight-linishly, I walk over and join her. Turning to her with an enormous smile, I ask what she thought of the ceremony on Gartenstrasse. She is smiling, too, but there is also a look of wonder on her angelic face, as if she has witnessed something truly remarkable. When she speaks, her voice is so tender and soft that I have to lean close to hear her words above the room's cheerful din.

“Tonight,” she says, “was like a birth, the birth of a star whose light we cannot see for hundreds of years.” Dietgard hugs me and whispers in my ear, “Alex was with us at the birth.”

“Thank you,” I breathe. If I have ever felt this deeply happy before, I cannot remember it.

An hour or so later, the last of the guests take their leave. Alex's wake is at an end. Amy retires to bed and I drive Steven, Helen, and Deborah back to their hotel. I then leave the car in the hotel parking lot and walk down the road to Gartenstrasse. The clouds have cleared away, and there are now dozens and dozens of stars winking above the canopy of trees that lines the boulevard. Standing in front of the gate of my grandfather's house, I gaze with enormous pride and satisfaction and happiness at the plaque on the wall. I reflect that, while there will probably always remain a reservoir of sadness within me over what happened to my family, my feelings of guilt and shame have largely vanished. The end of my journey has borne a new beginning.

I think of Dietgard's declaration that tonight saw the birth of a new star, one that will join the galaxy I am seeing now above my head. And I am reminded of Juliet's wish for her beloved Romeo: “And when he shall die, take him and cut him out in little stars, and he will make the face of heaven so fine that all the world will be in love with night.” Tonight the light I see reflected from the plaque seems to promise a kind of immortality for my lost family. Alex and Helmut, Toni and Eva, and all of us have come home, and we are safe and happy.

And so, dear Reader, should your travels take you to Oldenburg, I invite you to pay a visit to 34 Gartenstrasse and look up, with a smile and not a tear, at the shining stars.

A journey both metaphorical and practical, such as the one I've described in this book, cannot even be conceived, much less realized, without some extraordinary assistance. I'm eager to express my deep and profound thanks to the many wonderful people who offered their help and guidance along the way.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., is an invaluable resource, both for its countless documents and, especially, for its staff of archivists and researchers. Many thanks to Michlean Amir, Diane Afoumado, Marc Masurovsky, and Scott Miller; one of the USHMM's indefatigable European-based investigators, Peggy Frankston; and photo archivists Judith Cohen, Nancy Hartman, and Caroline Waddell.

I learned an immense amount of detail regarding the voyage of the

St. Louis

and the negotiations surrounding her return to Europe within the archives of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in New York City. Staff researcher Misha Mitsel made my visit to the Joint particularly rewarding.

A special word of thanks to Herbert Karliner of Miami for sharing his memories of being a twelve-year-old passenger on board the

St. Louis

.

Singular thanks to Vicki Caron, the Diane and Thomas Mann Professor of Modern Jewish Studies at Cornell University, for generously providing me with a valuable article about the agricultural camp at Martigny-les-Bains and for passing on her vast knowledge of resources in Paris.

And my deepest thanks to three superb translators who enabled me to make sense of the many shards of evidence and remembrance I collected

along the way: Alice Kelley, Christa Dub, and Margot Dembo.

Merci

and

vielen Dank

!

Once we landed in Europe, our path was made infinitely smoother and much more pleasant and worthwhile thanks to the following people: Anne and Theodor Beckmann, Erika Sembdner, Rita Schewe, and Oliver Glissmann in Sachsenhagen; and Hiltrud and Roland Neidhardt, Farschid Ali Zahedi, Dietgard Jacoby, Joerg Witte, Ottheinrich Hestermann, Annemarie Boyken, Anneliese Wehrmann, and Monica and Carsten Meyerbohlen in Oldenburg.

In France we received gracious assistance from Maurice Flamangin in Boulogne-sur-Mer; Madame Gerard Liliane and Julien Duvaux in Martigny-les-Bains; Monique and Jean-Claude Drouilhet in Montauban; Irene Dauphin in Agde; Elodie Montes and Marianne Petit in Rivesaltes; Odette Boyer and Katell Gouin in Les Milles; and Ingrid Janssen, Caroline Didi, and the archivists of the Museum of the Shoah in Paris. Thanks also to Piotr Supinski at the Memorial Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

I'd like to take a moment for a posthumous note of thanks to Bob Silverstein, my former agent, who succumbed to cancer in October 2012. Bob was a reliable source of cheer and encouragement and I'll always remember our jolly dinner in Paris. Sincere thanks also to Bob's sister-in-law, Zohra Belkadi, who unearthed a number of valuable leads from her home in Lyon.

A hearty thank you to my new agent, Jim Levine, for believing in this project enough to take me on as a client and for finding

Alex's Wake

a home at Da Capo Press. Many, many thanks to Da Capo's executive editor, Bob Pigeon, for his incredible enthusiasm, bracing humor, and perceptive work in shaping the manuscript. Thanks also to publisher John Radziewicz, project editor Mark Corsey, marketers Kevin Hanover and Sean Maher, publicist extraordinaire Lissa Warren, and the rest of the magnificent Da Capo team. And a spirited

go raibh maith agat

to the McShea Institute for Irish Studies.

Closer to home, I'd like to thank Tamara Meyer for organizing and maintaining her monthly gatherings of second generation Jews. Warm thanks to the groupâVicki Killian, Anne Masters, Roy Kahn, Julie Litten, Carol Schaengold, Paul Meyer, and Diane Castiglioneâfor being a source of comfort as we continue to try to understand What It All Means. Special thanks to Vicki and three dear friends, Glen and Lauren Howard and Robert Aubry Davis, for reading early drafts of the manuscript and making so many valuable suggestions.

My profound appreciation and love to my new-found family members, Helen and Steven Behrens, and my cousin of long standing, Deborah Philips, for making the journey to Oldenburg and participating in the ceremony on Gartenstrasse.

Finally, and very simply, I could never have undertaken this journey without my wife and traveling companion, Amy Roach. The words “thank you” have never seemed so inadequate. YVOB