Alex's Wake (47 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

One of the rooms in Barracks 20 is dimly lit and a small trough of earth-colored gravel lines the base of each wall. I borrow a small pair of nail scissors from Amy and slowly and carefully separate Helmut's photo from Alex's. I then kneel by one of the gravel borders, kiss Helmut's seventeen-year-old face, softly say, “I love you,” and place the photo onto the gravel, where it leans against the wall. This is the loving burial my sweet uncle never had, and as I bow my head, my tears drip onto the tiny crushed stone.

“Ruhe ruhig, mein liebe Helmut,”

I whisper. “Rest in peace.”

In silence, we walk slowly back to the parking lot and then drive the two kilometers to Birkenau. Here there are fewer cars and only a single tour bus. The remains of the camp seem vast in comparison to the tidy Auschwitz memorial. At Auschwitz there are many small brick buildings connected by well-groomed gravel paths; here there are only a handful of wooden barracks slowly rotting in the wind and weather of the Polish countryside, surrounded by large empty fields of tall grasses that bend in the breeze of this warm June day. The Auschwitz camp is alive with visitors crunching along the paths, snatches of their varied languages competing for attention. Birkenau is all sad silence; conversations are hushed and muted; what sounds there are come largely from nature: the wind sighing in the grass, the occasional bird song, crickets.

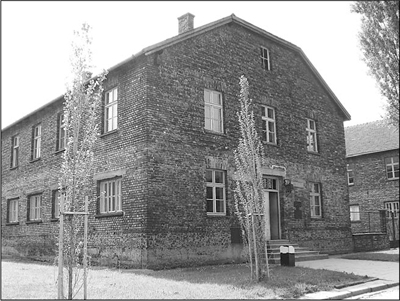

Barracks 20 at Auschwitz, where Uncle Helmut died, either of typhus or of a deliberate lethal injection, and where I left his photograph

.

A memorial plaque, on which visitors have placed many small stones, reads, “Forever let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity, where the Nazis murdered about one and a half million men, women, and children, mostly Jews, from various countries of Europe. Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1940â1945.”

The parking area abuts the elevated guard tower that straddles a single railway line; together the tower and track form one of the indelible images of the Holocaust. Amy and I walk inside the gates of Birkenau

to stand in the shadow of the tower at the approximate point where the selections were made, where Alex and Helmut were separated by the wave of a Nazi doctor's hand.

They were father and son, they had been constant companions for more than three years, becoming each other's best friend, on sea and then on land, in Boulogne-sur-Mer and Martigny-les-Bains, in Sionne and Montauban, Agde and Rivesaltes and Les Milles, and finally on those terrible trains to Drancy and then to this very spot. And then, in the blink of an eye, Alex was sent to the left and Helmut was sent to the right. Did they know what was in store for each of them? Were they permitted a last embrace, a final handclasp, anything at all? Did father cry out to son, son to father? Could they have heard each other over the wail of humanity at the scene of this unspeakable crime?

I am gasping for breath, my legs suddenly too weak to support me, and I very nearly collapse, but Amy gathers me in her arms and we rock together back and forth, back and forth, until my heartbeat returns to normal and my eyes can see again.

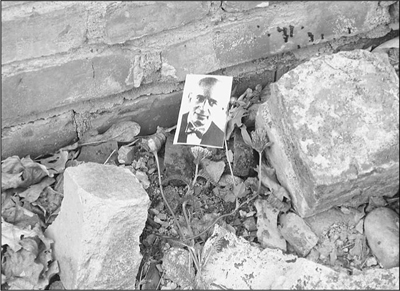

When I have regained my strength, we slowly walk several hundred yards to the site of two of the crematoria, both of which were nearly destroyed by the retreating German army in January 1945, as they sought to cover up their deeds. Today the crematoria are harmless holes in the ground, bordered by low brick walls and crumbling concrete. From a nearby field, I pluck three little wildflowers, one yellow, one purple, one white, and then jump lightly down into what remains of one of the crematorium's foundations. I place my grandfather's photo on the ground, leaning it against the bricks, and then lay the flowers beneath the photo. “Goodbye, Alex,” I whisper, “I love you so much.

Ruhe ruhig

.” Amy hugs me again, and I hold her as I weep.

Then I dry my eyes, take a final look at the photo and the flowers and climb up out of the grave. It is time, I tell myself. It is now time to let go.

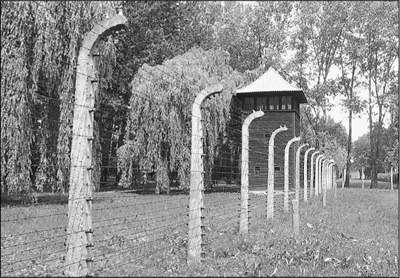

For the next ten or twenty minutes, we sit with our backs against a tree, taking refuge in its shade against what has become quite a warm and humid day. We face away from the ruined crematoria and toward the boundaries of Birkenau. The barbed wire enclosing the camp is affixed to concrete pillars that curve inward gracefully as they crest, and I am reminded of a fragment of a poem written by a young prisoner who was held here seventy years ago. Zofia Grochowalska Abramovicz also noticed those graceful curves strung with wire and called them “the harps of Birkenau,” writing that the wind made the cruel wires vibrate and utter pleasing sounds. What a sweet soul Zofia must have possessed, I think, to find a little beauty amid such cruelty and ugliness.

Alex's “burial site” in the ruined foundations of one of the crematoria in Birkenau

.

I close my eyes and hear the wind whispering and rustling in the green leaves overhead and imagine that I hear a thin and distant melody in the ghostly strings of Zofia's harps. Then a cow moos and a rooster crows from a nearby farm and I realize that life is everywhere. Birkenau's instruments of death are indeed in ruins, and they can no longer harm me. Alex and Helmut's journey, painful and hopeless as it turned out to be, ended here. I need to acknowledge that it ended, that they died here, but also that I am alive, that I have survived. Having followed in Alex's wake for so long, now that I have come to the spot where he died I must resolve, for the rest of the time that I'm given, to live life to the fullest.

A few of the graceful harps of Birkenau

.

“C'mon,” I say to Amy, “let's get the hell out of here.”

We drive away from Oswiecim toward a few days of rest in the Swiss Alps. After weathering a long, construction-induced traffic jam on the Polish-Czech border, we head west on a clear stretch of open road in the beautiful Czech countryside, toward a glorious sunset. I have brought along a recording of the Mass in B Minor by Johann Sebastian Bach, whose birthplace we visited two days ago, and as the Meriva purrs along, we listen to the Mass's last two movements.

Dame Janet Baker, one of my favorite artists, sings

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis

. (“O Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.”) It occurs to me that it would have to be a lamb of immense strength and fortitude to take away all of the sins committed at Auschwitz. Perhaps, I think, it is an impossible task; perhaps some sins will outlast us all.

But then comes Bach's final magnificent chorus on the words

Dona nobis pacem

(“Grant us peace”). The music soars, carrying voice and spirit ever upward. If anything can restore my abiding faith in the human animal, this glorious creation can, and does. My dear wife and traveling companion sings along with me, and I think to myself, “Let my journey grant Alex and Helmut peace. Let them rest in the earth and sky of Poland forevermore. And may it grant me peace as well.”

“J

OURNEYS END IN LOVERS MEETING

.”

That song from

Twelfth Night

â“It Was A Lover and His Lass”âsounded through my mind as we made the trans-Atlantic crossing on the solstice, June 21, and flew back to the States. From the haunted, death-soaked soil of Auschwitz, we had driven south and west to the clear, bracing air of the Swiss Alps to spend our last days in Europe amid the old-world luxury of a grand hotel. Amy's Uncle Jim, a professor and diplomat, loved to stay at the Hotel Waldhaus in Sils-Maria, an inn that has been owned and operated by the same family since 1908, and we came in remembrance of him. Three days of Alpine hiking and gourmet dining did much to restore our bodies and souls. On the morning of the longest day of the year, we returned our faithful little Meriva to the rental agency. Its odometer now read 20,177; in our six weeks on the road, we had driven 9,214 kilometers, or 5,725 miles, nearly twice the width of the United States.

On the plane ride back to Washington, I reflected that those six weeks seemed to have lasted a long, long time and yet to have passed in the blink of an eye. I recalled that before I left, I had feared both that I would be unable to uncover much information about Alex and Helmut's lives and that the trip would feel more of a mockery of Alex and Helmut's suffering than a tribute to them. Looking down on the world from thirty-six thousand feet, I decided that those fears had not been realized.

I had learned a great deal, factually, from the archives in Bückeburg and Helmut's school records in Oldenburg; from the newspaper clippings in Boulogne and the saga of Adolphe Poult and René Bousquet in Montauban. And I learned a lot, viscerally, at Barracks 21 in Rivesaltes and Barracks 7 and 20 in Auschwitz.

How deeply moving it had been to stand where Alex and Helmut had stood, to see what they saw, to feel just a bit of what they felt, if not the danger and terror they experienced. I recalled walking the docks of Boulogne, imagining how hopeful they must have felt as their ship pulled into what must have finally seemed like a safe harbor. Driving through the smiling countryside of the Vosges, I again had imagined their hope as they saw the lovely fields and hillsides that might have become their new home. The ruins of the Hotel International in Martigny-les-Bains had sharply reminded me of the futility of that hope. Peering through the locked gates of the Poult factory gave me the first inklings of what they must have felt as prisoners and enemies of the Vichy state. And, oh, the bleak, windswept emptiness of Rivesaltes! It was there that their hope must have begun to die. The catacombs of Camp des Milles had given me the sense of being buried alive; the view of the boxcar from the brick factory's second floor was chilling in the June heat. And though I learned nothing of their final moments together on the railroad siding of Birkenau, I now had that terrible place forever fixed in my inner eye.

Dozing in my seat, lulled by the hum of the engines, I felt comforted by those thoughts and eager to begin setting them down. But Shakespeare's confident declaration kept occurring to me and giving me pause.

Journeys end in lovers meeting

. I patted Amy's arm and told myself that I had traveled with my lover these past six weeks; how then could I meet her when our plane landed at Dulles Airport? Closing my eyes, I thought, “Old Will can't be right about everything.”

As it happened, however, my journey was not quite at its end.

What actually greeted me upon our arrival was what Winston Churchill called his “black dog”âa shroud of depression that descended on me over the next several weeks as I found it difficult to shake off the sadness brought on by those hours in Auschwitz. Perhaps it was merely

the routine of daily life following the exciting days of discovery on the road. But I was also constantly conscious of one overwhelming and incontrovertible fact: impossible though it was, I had failed to save Alex and Helmut, those six weeks and fifty-seven hundred miles notwithstanding. Auschwitz was the punch line to their story after all. The bad guys had won and my family had lost; never mind my good intentions, I had been no more successful in preventing the murders than my father had been. That, at least, is how it seemed to me during the long summer days. The hopes I had felt as I drove away from Poland were proving difficult to sustain.