All Hell Let Loose (41 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

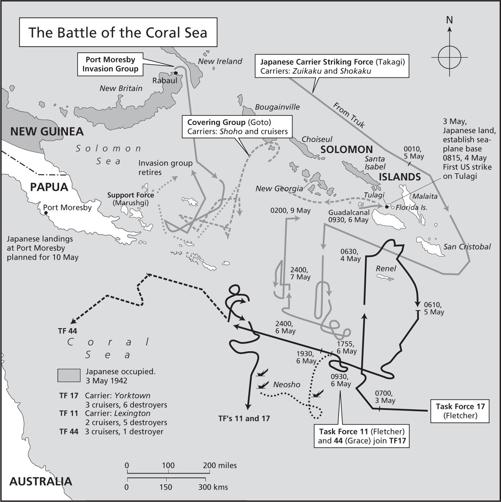

But the battle was done: both fleets turned away. Fletcher’s task groups had lost 543 lives, sixty aircraft and three ships including

Lexington

. Inoue lost over 1,000 men and seventy-seven aircraft – the carrier

Zuikaku

’s air group suffered heavy attrition. But the balance of destruction favoured the Japanese, who had better planes than the Americans and handled them more effectively. Amazingly, however, Inoue abandoned the operation against Port Moresby and retired, conceding strategic success to the US Navy. Here, once again, was a manifestation of Japanese timidity: victory was within their grasp, but they failed to press their advantage. Never again would they enjoy such an opportunity to establish dominance of the Pacific.

In the course of the war, the US Navy would show itself the most impressive of its nation’s fighting services, but it faced a long, harsh learning process. Several early commanders were found wanting, because they were slow to grasp the principles of carrier operations, which would dominate the Pacific campaign. American fliers’ courage was never in doubt, but at the outset their performance lagged behind that of their enemies. At Pearl Harbor, albeit against an unprepared and static enemy, Japanese planes achieved the remarkable record of nineteen hits and detonations out of forty torpedo launches, a record no other navy matched. When US carrier planes attacked Tulagi anchorage on 3 May 1942 against slight opposition, twenty-two Douglas Devastator torpedo-bombers achieved just one hit. Attacking

Shokaku

two days later, twenty-one Devastators scored no hits at all. Most American torpedoes, the Japanese said later, were launched too far out, and ran so slowly that they were easily avoidable.

Among US naval aircraft, the Coral Sea battle showed that the Dauntless dive-bomber was alone up to its job, not least in having adequate endurance. The Devastator was ‘a real turkey’, in the words of a flier, further handicapped by high fuel consumption. Worst of all, Mk 13 aerial and Mk 14 sea-launched torpedoes were wildly unreliable, unlikely to explode even if they hit a target. A most un-American reluctance to learn from experience meant that this fault, afflicting submarine as much as air operations, was not fully corrected until 1943.

War at sea was statistically much less dangerous than ashore for all participants save such specialists as aviators and submariners. Conflict was impersonal: sailors seldom glimpsed the faces of their enemies. The fate of every ship’s crew was overwhelmingly at the mercy of its captain’s competence, judgement – and luck. Seamen of all nations suffered cramped living conditions and much boredom, but peril intervened only in spasms. Individuals were called upon to display fortitude and commitment, but seldom enjoyed the opportunity to choose whether or not to be brave. That was a privilege reserved for their commanders, who issued the orders determining the movements of ships and fleets. The overwhelming majority of sailors, performing technical functions aboard huge sea-going war machines, made only tiny, indirect personal contributions to killing their enemies.

Carrier operations represented the highest and most complex refinement of naval warfare. ‘The flight deck looked like a big war dance of different colors,’ wrote a sailor aboard

Enterprise

. ‘The ordnance gang wore red cloth helmets and a red T-shirt when they went about their work of loading machine-guns, fusing bombs, and hoisting torpedoes … Other specialties wore different colors. Brown for the plane captains – one attached to each plane – green for the hydraulic men who manned the arresting gear and the catapults, yellow for the landing signal officer and deck control people, purple for the oil and gas kings … Everything was “on the double” and took place with whirling propellers everywhere, waiting to mangle the unwary.’ The US Navy would refine carrier assault to a supreme art, but in 1942 it was still near the bottom of the curve: not only were its planes inferior to those of the Japanese, but commanders had not yet evolved the right mix of fighters, dive-bombers and torpedo-carriers for each ‘flat-top’ – after the Coral Sea, captains deplored the inadequate proportion of Wildcats. US anti-aircraft gunnery was no more effective than that of the Royal Navy. Radar sets were short-sighted in comparison with those of the later war years. Damage control, which became an outstanding American skill, was poor.

The US Navy boasted a fine fighting tradition, but its 1942 crews were still dominated by men enlisted in peacetime, often because they could find nothing else to do. Naval airman Alvin Kiernan wrote:

Many of the sailors were there, as I was, because there were few jobs in Depression America … We would have denied that we were an underclass … There wasn’t such a thing in America, we thought – conveniently forgetting that blacks and Asians were allowed to serve in the navy only as officers’ cooks and mess attendants. Our teeth were terrible from Depression neglect, we had not always graduated from high school, none had gone to college, our complexions tended to acne, and we were for the most part foul-mouthed, and drunkenly rowdy when on liberty … I used to wonder why so many of us were skinny, bepimpled, sallow, short and hairy.

Cecil King, chief ship’s clerk on

Hornet

, recalled: ‘We had a small group of real no-goodniks. I mean these kids were not necessarily honest-to-God gangsters, but they were involved in anything that was seriously wrong on the ship – heavy gambling and extortion. One night one of them was thrown over the side.’ For most men, naval service required years of monotony and hard labour, interrupted by brief passages of violent action. A few, including King, actively enjoyed carrier life: ‘I just felt at home at sea. I felt like that’s what the Navy’s all about. Many times I would wander around the ship, particularly in the late afternoon, just enjoying being there. I would go over to the deck edge elevator and stand and watch the ocean going by. I feel like I’m probably one of the luckiest people in the entire world … for having been born in the year that I was, to be able to fight for my country in World War II; this whole era … is something that I feel real privileged for having gone through.’

The expansion of the US Navy’s officer corps made a dramatic and brilliant contribution to the service’s later success, and some learned to love the sea service and the responsibilities it conferred on them. Most ordinary sailors, however – especially as ships began to fill with wartime recruits – did their duty honourably enough, but found little to enjoy. Some found it all too much for them: a sailor on

Hornet

climbed out on the mast yardarm, and hung 160 feet over the sea trying to muster nerve to jump and kill himself until dissuaded by the chaplain and the ship’s doctor. He was sent to the US for psychiatric evaluation – and eventually returned to

Hornet

in time to share the ship’s sinking, the fate of which he had been so fearful.

Those who experienced the US Navy’s early Pacific battles saw much of failure, loss and defeat. The horrors of ships’ sinkings were often increased by fatal delays before survivors were located and rescued. The Pacific is a vast ocean, and many of those who fell into it, even from large warships, were never seen again. When the damaged light cruiser

Juneau

blew up after a magazine explosion on passage to the repair base at Espiritu Santu, gunner’s mate Allan Heyn was one of those who suddenly found himself struggling for his life: ‘There was oil very thick on the water, it was at least two inches thick, and all kinds of blueprints and documents floating around, roll after roll of toilet paper. I couldn’t see anybody. I thought: “Gee, am I the only one here” … Then I heard a man cry and I looked around it was this boatswain’s mate … He said he couldn’t swim and he had his whole leg torn off … I helped him on the raft … It was a very hard night because most of the fellows were wounded badly, and they were in agony. You couldn’t recognize each other unless you knew a man very well before the ship went down.’ After three days, their party had shrunk from 140 men to fifty; on the ninth day after

Juneau

’s loss, the ship’s ten remaining survivors were picked up by a destroyer and a Catalina flying boat. Sometimes, vessels vanished with the loss of every man aboard, as was almost always the case with submarines.

The Japanese began the war at sea with a corps of highly experienced seamen and aviators armed with the Long Lance torpedo, most effective weapon of its kind in the world. Their radar sets were poor, and many ships lacked them altogether. They lagged woefully in intelligence-gathering, but excelled at night operations, and in early gunnery duels often shot straighter than Americans. Their superb Zero fighters increased combat endurance by forgoing cockpit armour and self-sealing fuel tanks. The superiority of Japanese naval air in 1942 makes all the more astonishing the outcome of the next phase of the war in the Pacific.

Admiral Yamamoto strove with all the urgency that characterised his strategic vision to force a big engagement. Less than a month after the bungled Coral Sea action, he launched his strike against Midway atoll, committing 145 warships to an ambitious, complex operation intended to split US forces. A Japanese fleet would advance north against the Aleutians, while the main thrust was made at Midway. Nagumo’s four fleet carriers –

Zuikaku

and

Shokaku

were left behind after their Coral Sea mauling – would approach the island from the north-west, with Yamamoto’s fast battleships three hundred miles behind; a flotilla of transports, carrying 5,000 troops to execute the landing, would close from the south-west.

Yamamoto may have been a clever man and a sympathetic personality, but the epic clumsiness of the Midway plan emphasised his shortcomings. It required him to divide his strength; worse, it reflected characteristic Japanese hubris, by discounting even the possibility of American foreknowledge. As it was, Admiral Chester Nimitz, the US Navy’s Pacific Commander-in-Chief, knew the enemy was coming. By one of the war’s most brilliant feats of intelligence work, Commander Joseph Rochefort at Pearl Harbor used fragmentary Ultra decrypts to identify Midway as Nagumo’s objective. On 28 May the Japanese switched their naval codebooks, which thereafter defied Rochefort’s cryptographers for weeks. By miraculous luck, however, this happened just too late to frustrate the breakthrough that betrayed Yamamoto’s Midway plan.

Nimitz made a wonderfully bold call: to stake everything upon the accuracy of Rochefort’s interpretation. Japanese intelligence, always weak, believed that

Yorktown

had been sunk at the Coral Sea, and that the other two US carriers,

Hornet

and

Enterprise

, were far away in the Solomons. But heroic efforts by 1,400 dockyard workers at Pearl Harbor made

Yorktown

fit for sea, albeit with a makeshift air component. Nimitz was therefore able to deploy two task groups to cover Midway, one led by Fletcher – in overall command – and the other by Raymond Spruance. This would be a carrier action, with Nagumo’s flat-tops its objectives; the slow old American battleships were left in Californian harbours. The navy’s planes were recognised as the critical weapons.

Almost a century earlier, Herman Melville, America’s greatest novelist of the sea, wrote: ‘There is something in a naval engagement which radically distinguishes it from one on land. The ocean … has neither rivers, woods, banks, towns, nor mountains. In mild weather, it is one hammered plain. Stratagems, like those of disciplined armies, ambuscades – like those of Indians – are impossible. All is clear, open, fluent. The very element which sustains the combatants yields at the stroke of a feather … This simplicity renders a battle between two men-of-war … more akin to the Miltonic contests of archangels than to the comparatively squalid tussles of earth.’

In 1942, Melville’s lyrical vision of the sea remained recognisable to another century’s sailors, but two factors had transformed his image of naval battle. First, communication and interception made possible ‘ambuscades and stratagems’, such as that which took place at Midway – the location and pre-emption of the enemy before his figurative sails were sighted. Superior American radar conferred another important advantage over the Japanese. Meanwhile, the advent of air power meant that all was no longer ‘clear, open, fluent’: rival fleets became vulnerable to surprise while hundreds of miles apart. But exactitude of knowledge was still lacking. In a vast ocean, it remained hard to pinpoint ships, or even fleets. Rear-Admiral Frank Fletcher said: ‘After a battle is over, people talk a lot about how the decisions were methodically reached, but actually there’s always a hell of a lot of groping around.’ This had been vividly demonstrated by the Coral Sea engagement; despite Commander Rochefort’s magnificent achievement, uncertainty and chance also characterised Midway.