All Hell Let Loose (42 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

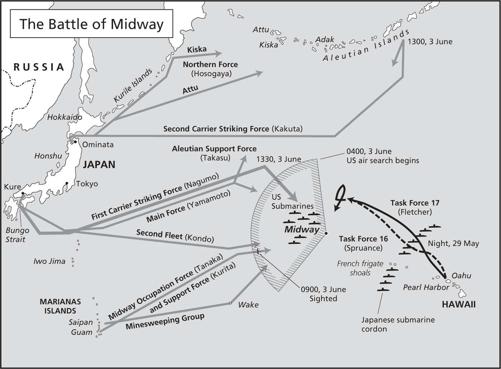

The engagement was fought only six months after Pearl Harbor, when the US Navy still had fewer carriers than the British, though they carried many more planes. The two American task groups were deployed too far apart to provide mutual support, or effectively to coordinate their air operations. On 3 June, the first skirmish took place: at 1400, nine land-based B-17 Flying Fortresses delivered an ineffectual attack on the Japanese amphibious force. Early that morning also, Japanese aircraft launched a heavy attack on the Aleutians. For tens of thousands of men on both sides, a tense night followed. The garrison of Midway prepared to sell their lives dearly, knowing the fate that had already befallen many other island defenders at Japanese hands. On the US carriers three hundred miles to the north-east, aircrew readied themselves to fight what they knew would be a critical action. One of them, Lt. Dick Crowell, said soberly as they broke up a late-night craps game on

Yorktown

: ‘The fate of the United States now rests in the hands of 240 pilots.’ Nimitz was satisfied that the scenario was unfolding exactly as he had anticipated. Yamamoto was troubled that the US Pacific fleet remained unlocated, but he remained oblivious that any carriers might close within range of Nagumo.

Before dawn next morning, ‘a warm, damp, rather hazy day’, American and Japanese pilots breakfasted.

Yorktown

’s men favoured ‘one-eyed sandwiches’ – an egg fried in a hole in toast. Nagumo’s fliers enjoyed rice, soybean soup, pickles and dried chestnuts before drinking a battle toast in hot

sake

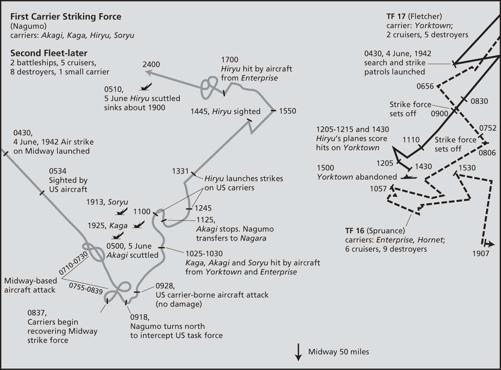

. At 0430 seventy-two Japanese bombers and thirty-six fighters took off to attack Midway island. At 0545, a patrolling Catalina signalled the incoming attack, then spotted Nagumo’s carriers. Fletcher needed three hours’ steaming to close within attack range. Meanwhile, Midway-based Marine and army torpedo-bombers and bombers took off immediately, as did Wildcat and Buffalo fighters. The latter suffered terribly at the hands of Zeroes: all but three of twenty-seven were either shot down or so badly damaged that they never flew again. But the Japanese attackers, in their turn, lost 30 per cent of their strength.

Nagumo’s bomber attack, at 0635, inflicted widespread damage but failed to knock out Midway’s airfields. Its leader signalled the fleet: ‘Second strike necessary.’ Thereafter, nothing went right for the Japanese admiral. His first mistake of the day had been to dispatch only a handful of reconnaissance aircraft to search for American warships; one seaplane, from the heavy cruiser

Tone

, was delayed taking off – and it was vectored to search the sector where Fletcher’s carriers were steaming. Thus, Nagumo was still ignorant of any naval air threat when he received the signal from his Midway planes. At 0715 he ordered ninety-three ‘Kate’ strike aircraft, ready with torpedoes on his decks, to be struck below and re-armed with high-explosive bombs to renew the attack on the island, meanwhile clearing the way for the returning Midway planes to land on.

Even as they did so, ships’ buglers sounded another air-raid alarm. Between 0755 and 0820, successive small waves of Midway-based US aircraft attacked Nagumo’s fleet. They had no fighter cover, and were ruthlessly destroyed by AA fire and Zeroes without achieving a single hit. The gunfire died away, the drone of the surviving attackers’ engines faded. Meanwhile, the first of Spruance’s torpedo planes and dive-bombers were already airborne, heading for the Japanese fleet from extreme range. Although

Tone

’s scout plane belatedly spotted the American ships, only at 0810 did its pilot report that they seemed to include a carrier. Among Nagumo’s staff, this news prompted a fierce argument about how to respond, which continued even as the last of the US land-based attacks was repulsed.

The only achievement of the strikes from Midway, purchased at shocking cost, was to impede flight operations aboard the Japanese carriers. Nagumo was hamstrung by the need to recover his attack force, short of fuel, before he could launch a strike against Fletcher’s fleet; meanwhile, he ordered the ‘Kates’ in the hangars once more to be armed with torpedoes. By far his wisest course, at this stage, would have been to turn away and open the range with the enemy, until he had reorganised his air groups and was ready to fight. As it was, however, with characteristic lack of initiative he held course. At 0918, the Japanese flight decks were still in chaos as aircraft completed refuelling, when picket destroyers signalled another warning, and began to make protective smoke. The first of Fletcher’s planes were closing fast, and Zeroes scrambled to meet them.

Before the American fly-off, Lt. Cmdr. John Waldron, a rough, tough, much-respected South Dakotan who led Torpedo Eight from

Hornet

, told his pilots that the coming battle ‘will be a historic and, I hope, a glorious event’. Wildcat squadron commander Jimmy Gray wrote: ‘All of us knew we were “on” in the world’s center ring.’ Lt. Cmdr. Eugene Lindsey, commanding Torpedo Six, had been badly injured only a few days earlier when he ditched his plane after making a botched landing; his face was so bruised that it was painful for him to wear goggles. But on the morning of the Midway strike he insisted on flying: ‘This is what I have been trained to do,’ he said stubbornly, before taking off to his death.

The American attackers approached the Japanese in successive waves. Jimmy Gray wrote: ‘Seeing the white feathers of ships’ wakes at high speed at the far edge of the overcast, and realising that there for the first time in plain sight were the Japanese who had been knocking hell out of us for seven months was a sensation not many men know in a lifetime.’ The twenty escorting Wildcats flew high, while the Devastators necessarily attacked low. Over the radio, crackling dispute about tactics between fighters and torpedo-carriers persisted even as they approached the enemy. The Wildcats maintained altitude, and anyway lacked endurance to linger over the enemy fleet. The consequence was that when fifty Japanese Zeroes fell on the Devastators, these suffered a massacre. The twelve planes of Torpedo 3 were flying in formation at 2,600 feet and still fifteen miles from their targets when they met the first Japanese. Slashing attacks persisted throughout their run-in. One of the few surviving American pilots, Wilhelm ‘Doc’ Esders, wrote: ‘When approximately one mile from the carrier our leader apparently expected to attack, his plane was hit and it crashed into the sea in flames … I saw only five planes drop their torpedoes.’ Esders’ own Devastator was hit, his radioman fatally wounded; the CO

2

fire-bottle in the cockpit exploded; flak shells burst below them, while the Zeroes kept firing. The crew was extraordinarily lucky that the enemy planes turned away after following them homewards for twenty miles.

The Devastators ploughed doggedly towards their targets at their best speed of a hundred knots, until each wave in turn was shot to pieces and plunged into the sea. A bomber gunner heard Waldron talking over the radio as he led his planes in: ‘Johnny One to Johnny Two … How’m I doing Dobbs? … Attack immediately … There’s two fighters in the water … My two wingmen are going in the water.’ Waldron himself was last seen attempting to escape from his flaming plane. After the first wave had attacked, the Zeroes’ group leader reported laconically: ‘All fifteen enemy torpedo-bombers shot down.’ Many of the next wave were destroyed while manoeuvring to achieve an attack angle as the Japanese carriers swung wildly to avoid them. A despairing American gunner whose weapon jammed fired his .45 automatic pistol at a pursuing Zero.

George Gay, who flew from the

Hornet

at the controls of a Devastator, had a reputation in his squadron as a Texas loudmouth, but proved its only survivor. Shot down in the sea with a bullet wound and two dead crewmen, he trod water all day, having heard many stories about the Japanese shooting downed aircrew. At nightfall, he cautiously inflated his dinghy and had the fantastic good fortune to be picked up next morning by a patrolling American amphibian.

On the flight decks of Nagumo’s carriers, the Japanese experienced an hour of acute tension as the Devastators approached through a storm of anti-aircraft fire. But most of the torpedoes were dropped beyond effective range, and Mk 13s ran so slowly that the Japanese ships had ample time to comb their tracks. ‘I was not aware or did not feel the torpedo drop,’ said a Devastator gunner afterwards, adding that this was probably because his pilot was trying to jink. ‘A few days later I asked him when he dropped. He said when he realized that we seemed to be the only TBD still flying and that we didn’t have a chance of carrying the torpedo to normal drop range. I couldn’t figure out what he was trying to do and the flak was really bad, so I yelled into the intercom, “Let’s get the hell out of here!” It is possible that my yell helped him make his decision.’

Just after 1000, the attackers had shot their bolt, having achieved no hits. Of forty-one American torpedo-bombers which took off that day, only six returned, and fourteen of eighty-two aircrew survived. Most of the survivors’ planes were shot full of holes. Lloyd Childers, a wounded gunner, heard his pilot say, ‘We’re not going to make it.’ The Devastator reached the fleet, but was prevented from landing back on

Yorktown

by a gaping bomb crater in its flight deck. The pilot ditched safely in the sea alongside, and Childers patted his plane’s tail as it sank, in gratitude for getting him back. Many survivors, however, were enraged by the futility of their sacrifice, and embittered by the lack of protection from their own fighters. A Devastator gunner who landed back on

Enterprise

had to be forcibly restrained as he threw himself at a Wildcat pilot.

American fighters had few successes that day. One of them was achieved by Jimmy Thach, who went on to become one of the foremost naval aviation tacticians of the war. Thach said he lost his temper when he saw Japanese aircraft boring into his neighbour: ‘I was mad because here was this poor little wingman who’d never been in combat before, had had very little gunnery training, the first time aboard a carrier and a Zero was about to chew him to pieces … I decided to keep my fire going into him and he’s going to pull out, which he did, and he just missed me by a few feet; I saw flames coming out of the bottom of his airplane. This is like playing “chicken” with two automobiles on the highway headed for each other except we were both shooting as well.’

The Americans had suffered a shocking succession of disasters, which could easily have been fatal to the battle’s outcome. Instead, however, fortune changed with startling abruptness. Nagumo paid the price for his enforced failure to strike at Spruance’s task force even when he learned it was near at hand. Moreover, his Zeroes were at low level and running out of fuel when more American aircraft appeared high overhead, a few minutes after the last torpedo-bombers attacked.

The Dauntless dive-bomber was the only effective 1942 US naval aircraft; what followed changed the course of the Pacific war in the space of minutes. Dauntlesses fell on Nagumo’s carriers, wreaking havoc. ‘I saw this glint in the sun,’ said Jimmy Thach, ‘and it just looked like a beautiful silver waterfall, these dive-bombers coming down. It looked to me like almost every bomb hit.’ In reality, the first three bombs aimed at

Kaga

missed, but the fourth achieved a direct hit, setting off sympathetic detonations among munitions scattered across the carrier’s decks and in its hangars.

Soryu

and

Akagi

suffered similar fates. Wildcat pilot Tom Cheek was another fascinated spectator as the dive-bombers pulled out. ‘As I looked back to

Akagi

hell literally broke loose. First the orange-colored flash of a bomb burst appeared on the flight deck midway between the island structure and the stern. Then in rapid succession followed a bomb burst amidships, and the water founts of near-misses plumed up near the stern. Almost in unison

Kaga’s

flight deck erupted with bomb bursts and flames. My gaze remained on

Akagi

as an explosion at the midship water-line seemed to open the bowels of the ship in a rolling, greenish-yellow ball of flame …

Soryu

… too was being heavily hit. All three ships had lost their foaming white bow waves and appeared to be losing way. I circled slowly to the right, awe-struck.’