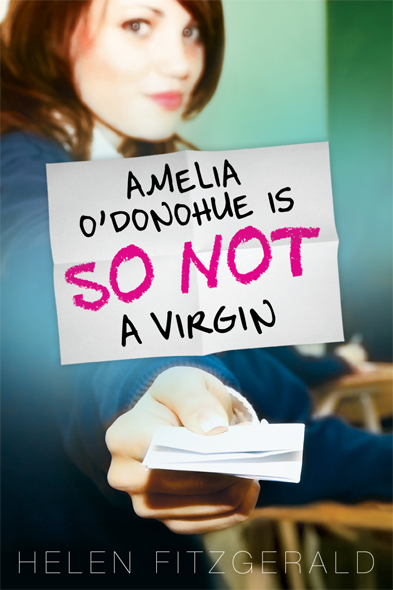

Amelia O’Donohue Is So Not a Virgin

Read Amelia O’Donohue Is So Not a Virgin Online

Authors: Helen FitzGerald

Copyright © 2010 by Helen FitzGerald

Cover and internal design © 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by JenniferJackman.com

Cover images © Con Tanasiuk/Design Pics/Corbis, Kenneth O’Quinn/iStock photo

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

teenfire.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my wonderful, funny daughter, Anna Casci

Contents

ONE

I

t was a typical breakfast except for two things.

The typical things:

- My mother sighed heavily and stared into space.

- Dad found corrupt politicians in

The Scotsman

and it made his lips go green.

Not typical things:

- The doorbell rang. It was Matt the postman with my fourth year exam results, as well as a congratulatory letter from the head teacher.

- I screamed.

History: A (top of class)

Physics: A (top of class)

Math: A (top of class)

English: A (equal top with Louisa MacDonald, who rang later hoping she’d beaten me but she hadn’t. Ha!)

Chemistry: A (top of class)

Biology: A (top of the world)

I blurted out my results to my mother and my father.

Just so you know, it had been a long time since I’d thought of my mother and my father as

Mum

and

Dad

. Mum and Dad, in my opinion, indicated some kind of intimacy, and I didn’t have any with my mother and my father. Not because of some massive disaster—like my mother drinking, or like my father bashing her head in with a saucepan when dinner’s crap, or like the death of a younger, better sibling—but because my mother and my father were emotional retards.

When I told my mother my results, she said, “Hard work pays off.” She had finished staring into space.

My father said, “Don’t let it go to your head.” He had finished with

The

Scotsman

.

But it was too late. It had

so

gone to my head that I screamed then rang all my friends.

And they were like, “Really?”

“I know; I can’t believe it!”

My ruddy-cheeked pal, Katie Bain, said, “We should celebrate! I’ve got it! A brisk walk to the standing stones and a picnic of Mum’s homemade oatcakes and Mrs. Goslan’s famous blackberry jam! Oh, and a thermos of hot chocolate! Steaming!”

Katie Bain only ever spoke with exclamation marks. I said maybe another time. There was a call waiting.

It was Louisa. She seemed a bit pissed off.

“But you did really well too!” I said.

(But not as well as me!)

Straight As.

Top of the class.

Top of the school in fact.

And my enormous success stayed in my head right up till dinner, by which time I’d ridden my bike all the way down my drive, along the two-mile coastal road and into the village to show the piece of paper to all of the above and their parents and their brothers and their sisters.

Only Louisa seemed interested in my results.

Her folks owned Aulay’s whitewashed pub. Aulay’s and the church bookended the seaside strip of fifteen houses and three shops. In her cozy bedroom above the bar, she read the letter with a scrunched up face, checking to see if they’d made a mistake, then said,

Wow!

The others said,

Oh great, gotta go to the post office/Pick some rosemary/You really should come to the standing stones!

So when I got home for supper, a fog of anticlimax had settled over me. Who cared if I did well? What would it change anyways?

As if to prove my theory, my mother told me to go to bed

at the stupidly early hour of 9:00 p.m. and said, “Say your prayers. Ask for humility.”

“Please god can I have some humility,” I said out loud.

She was like, “Properly.”

“Please god

may

I have some humility,” I said.

“And ask for forgiveness.”

“Please god forgive me…” I obeyed, then opened my eyes a tad and looked at my mother, who was standing over me, steely faced…“What for?”

“For your sins.”

“For my sins and god bless my mother and god bless my father and please may I go to Aberfeldy Halls. Amen.”

I wanted to go to Aberfeldy Halls more than anything in the entire universe. Louisa MacDonald and Mandy Grogan were going there. It was the best senior boarding school in the highlands. It had the best science grades in the UK. Nine out of ten graduates went on to university after going there.

I needed to go to university. I needed to do medicine and make money and live in the city, maybe even in London. At Aberfeldy Halls, you got your own cubicle and you studied for four hours every night. You got two choices for dinner. You got big shiny science labs and literature teachers who came from exotic countries and also wrote novels.

The outcome of my wish depended on the good lord apparently. (I am deliberately not using capitals.)

My mother said, “The good lord will tell us if you should go to Aberfeldy Halls. If you listen hard enough, you will hear.”

Listening to the good lord was very dull. Especially on Sundays, when the whole island did nothing but listen to the good lord, their ears pricked as they sat still in their living room seats, bibles in hand. No ferries; no cars; no shops; no television, talking, music, nothing. Just listening, waiting to be saved. From what? From boredom? From hour-like-minutes that ticked a sharp bird-beak into your skull?

They had plans for me, my parents. They wanted me, their only child, to stay on the island and be safe: tucked away from the evils and temptations of the city. They wanted me in our small croft house, where the ghosts of wet farmers from two hundred years ago lived with the ghosts of us. They wanted me to go to the local state school—a gray seventies scar on the outskirts of the village—where teachers yawned and pupils’ shoulders lowered with the hours. They wanted me to get just enough education to handcuff me to some god-fearing McFarmer for the rest of my life.

I had different plans. I longed to leave the island, my floating prison of rain, hunched shoulders, and the good lord. I was no

Katie Bain. I didn’t have red hair, freckles, and a cheeky grin. I didn’t collect rocks on beaches and get into mischief on hillocks. I didn’t want to know everyone or everything about them. I’d only lived in the city till I was nine, but I knew I was a city girl. I’d loved Edinburgh. I’d loved our old flat, a top floor tenement the size of Dundee, with floor-to-ceiling windows that looked out over the floodlit Castle, with neighbors who minded their own business, and with hide-and-seek nooks and crannies like the old maid’s room above the kitchen. When I used to open the bedroom window in my childhood flat, noises would fly at me: buses honking, people talking, even bagpipes piping from the touristy Princes Street. When I used to step outside, I’d be confronted with at least ten different things to do: Milkshake here? Dinner there? Movies over the road? Theatre round the corner? Dungeon up the hill? When I stepped out of the croft house, on the other hand, I was only ever confronted with a wind that bit my tonsils off.

I wanted crowds, noise, anonymity, difference. And I figured if I got a really good education, my parents couldn’t argue.

They’d say, “You got into Oxford?”

And I’d say, “I did!”

And they’d be like, “Well done, Rachel! You were right to go to Aberfeldy Halls. We’re proud of you.”

Because while my parents were emotional retards, I wanted to make them proud. I wanted to make them see that to be saved you must first dive into the water. If I dove first, perhaps they would follow. Perhaps they would be happy again.

• • •

The next morning, I decided that I needed to take serious action if my plan was ever going to work. I made my mind up that I would lie to my mother and my father. We were eating salty porridge at the kitchen table.

“I heard him,” I said.

“What was that?” my father asked, not looking up from the corrupt politicians in

The

Scotsman

.

“The good lord spoke. He told me I would go,” I said.

They’d never explained to me exactly how the good lord might tell us stuff, so I had no idea if this would work.

My mother squinted, staring at me, wondering.

“Last night. Clear as day…‘

Rachel, you are going to Aberfeldy Halls.

’” (I said this in a very deep godlike voice.)

“In that voice?”

“

his

voice. No doubt about it. I had been listening very hard.”

My mother was like, “Stop your nonsense.”

My father said, “That’s blasphemy, Rachel. Go to your room.”

I vowed there and then that when I visited them in their

ocean-view island retirement home and they turned to me and whispered, “I’ve been saved.” I would say, “Stop your nonsense and go to hell!”

My parents’ punishments had always been clear, firm, and followed-through-to-the-letter. When I was nine, they grounded me for seven days solid after I’d dropped my crisps in the back of the car and said the f word. When I was eleven, they grounded me for two weeks (no telephone calls or television) because I’d kissed a boy called James Connor in a game of Truth or Dare at Louisa MacDonald’s birthday party (Louisa’s older sister told her aunt, etc., etc.).

So when they asked me to go to my room, I obeyed, because not obeying would have serious repercussions. I spent hours lying on my bed dreaming of cinemas with movies from France and Germany, of Vietnamese restaurants, of people wearing strange hats and/or huge sunglasses, of markets selling crazy big bubble machines and vintage coats in all shapes and sizes.

Please, please oh non-existent god

, I said out loud,

may I go to Aberfeldy Halls.