Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

American Crucifixion (32 page)

The jury, laboriously chosen after extensive pretrial shenanigans, was perhaps the best that could be hoped for. There were no Mormons, but none of the twelve men had any discernible record of anti-Mormon agitation, either.

On Saturday morning, May 24, 1845, at 7:00 a.m., Young gaveled the first day into session.

Lamborn’s prosecution got off to a shaky start, as the prematurely decrepit attorney limped to the front of the courtroom. “The eyes of the whole country are upon us,” Lamborn intoned at the beginning of his rambling, disjointed opening statement. The case “has not only excited a feeling of considerable interest among the people of the United States, but throughout the civilized world.” He immediately struck a curious note of self-pity. “I came here under the direction of the governor, but I have to stand alone,” he told the jury, whose members were probably indifferent to his plight. “I have an array of learned Counsellors against one. I was commanded to seek assistance, but it cannot be had. I therefore stand alone, in this trial and in this community, unaided by council, to vindicate the Law of Man.”

It didn’t matter whether Joseph Smith was innocent or guilty of the charges that imprisoned him, Lamborn said, “but he has suffered an awful atonement, for any offence he might have committed . . . a reckless mob, came here, on these peacable prairies, and took that man from Jail and murdered him.” Then the prosecutor hectored his listeners, accusing them of complicity in Smith’s murder: “The guilt of this crime hangs over you, as a blight, and curse, which is destroying your character, and gnawing at the root of your prosperity. It is a blood stain upon your character, and a foul blot, which cannot be erased, but with vengeance, and rigour, to deal out the law, as the law is.”

One of the first witnesses he interrogated swore he had been in Westboro, Massachusetts, during June and July. Lamborn hadn’t bothered to interview him before the trial, which was not uncommon on the Illinois circuit, or elsewhere. The prosecutor wanted the next two witnesses to help him prove that Sharp and the militia commanders conspired to rally their troops for an attack on the Carthage jail, after Governor Ford had formally disbanded their troops. This argument hinged on testimony from Golden’s Point, from which most of the Warsaw militia had returned home as Ford had instructed, though some had proceeded to storm Carthage. But Lamborn’s first two witnesses had memory freeze. Militiaman John Peyton did remember Captain Aldrich calling for volunteers to march on Carthage. Lamborn pressed Peyton:

Q:

Did he say anything about Joseph Smith?

Peyton waited “some considerable time” to reply:

A:

I think he said that Joe Smith was now in custody, and the Mormons would elect the officers of the county, and by that means Joe would select his own jury and get free . . .

Q:

Was anything said about killing Joseph Smith?

A:

No.

Q:

Did [Aldrich] say what should be done with him?

A:

No . . .

Q:

Then it was Aldrich that was in favor of going to Carthage?

A:

I don’t know that it was Aldrich, or some other of them. There was something said in the crowd about going to Carthage, I think.

Q:

What did the people there, upon the ground, in common with these men, say they were going to Carthage for?

A:

I could not tell what their intention was. They did not say.

Unable to extract a confession, Lamborn turned to his next witness. He called Lieutenant Franklin Worrell to the stand. Worrell commanded the ineffectual corps of six guards stationed right in front of the Carthage jail. He would testify that some of the guards were lollygagging at the bottom of the jailhouse staircase when the marauders snuck up along the fence next to the jail. Worrell, the shopkeeper and assistant postmaster, was well known and well liked in Carthage.

Predictably, the witness reported that there was much confusion during the assault. “There was a great crowd,” he said, “as thick as in this courtroom. Their pieces were going off all the time and [there was] so much noise and smoke that I could not hear anything what was said or done.”

Lamborn never asked why Worrell and the Greys had so spectacularly failed to offer any resistance to the mob. Instead, he inquired if Worrell saw any of the defendants at the jail.

No, Worrell replied. Although he said he did recall seeing Aldrich and Williams in Carthage afterward.

Under questioning, Worrell allowed that as a successful storekeeper, he knew about one-third of the residents of Hancock County.

So did you recognize any members of the mob who assaulted the jail? Lamborn asked.

No, Worrell said.

Worrell, who had stood in the eye of the storm in front of the Carthage jailhouse, yielded absolutely nothing to Lamborn’s muddled queries. With no substantial testimony to refute, Browning and the defense declined to cross-examine.

A few moments later, Lamborn shocked the courtroom by recalling Worrell to the witness stand.

Objection! Browning cried. He and Lamborn approached Judge Young.

Browning had a solid argument. Because there had been no cross-examination, there were no new facts to justify Worrell’s recall. Lamborn had taken his bite at the apple, and there was no rule of procedure that guaranteed him another one. But Lamborn’s powers of suasion triumphed. Young ruled that Worrell could continue testifying, as long as Lamborn agreed to open new lines of questioning.

The prosecutor had new questions, plugging the huge gaps in his earlier, slipshod inquiries.

Q:

Do you know if the Carthage Greys, that evening, loaded their guns with blank cartridges?

Objection! “You need not answer that question,” Browning shouted.

A:

I will not answer that question, I know nothing about the Carthage Greys, only the six men that I had to do with.

Q:

Did those six men load their guns with blank cartridge that evening?

A:

I will not answer it.

Young affirmed Worrell’s right not to answer a question that might incriminate himself, and Worrell took the hint. The next time Lamborn asked, Worrell again declined to answer. No one would ever know whether the Greys were protecting Joseph with unloaded guns, or not.

Writing many years later, John Hay commented that “it would be difficult to imagine anything cooler than this quiet perjury to screen a murder.”

CAME NOW THE TRIAL’S MOST SENSATIONAL WITNESS, TWENTY-four-year-old William Daniels, a cooper and recent Mormon convert who claimed to have seen and heard every detail of the conspiracy to kill Joseph Smith. Daniels supposedly remembered the events of the previous June as if they happened yesterday. Daniels insisted that the deceased Joseph Smith had appeared to him in a vision and escorted him to a mountaintop. There, the Prophet offered the impressionable lad a “glass of clear, cold water,” blessed him, and urged him to tell all he knew about the murders. Daniels was so confident of his story that he had printed it up as a pamphlet, “Correct Account of the Murder of Generals Joseph Smith and Hyrum Smith at Carthage, on the 27th Day of June, 1844” and had started selling copies two weeks before the trail for 25 cents apiece.

Daniels said he had ridden out of Warsaw with the militias and was present at the fateful meet-up near Golden’s Point. He wrote in the pamphlet that defendant Thomas Sharp riled up the troops with a stem-winding, Mormon-hating speech, urging them to end “the mad career of the Prophet.” Per Daniels, Sharp urged the assembled militias to murder the Smiths while Governor Ford was visiting Nauvoo, and “we shall then be rid of the d——ed little Governor and the Mormons, too.” Daniels even reproduced the supposed text of the letter from the Carthage Greys, urging the Warsaw irregulars to storm the jail:

Now is a delightful time to murder the Smiths. The governor has gone to Nauvoo with all the troops. The Carthage Greys are left to guard the prisoners. Five of our men will be stationed at the jail; the rest will be upon the public square. To keep up appearances, you will attack the men at the jail—a sham scuffle will ensue—their guns will be loaded with blank cartridges—they will fire in the air.

Under Lamborn’s prodding, Daniels revealed even more details about the decision to attack Carthage. According to his account, Captain Jacob Davis said he would rather go home than march on Carthage. An earlier witness testified he heard Davis “say he’d be d——d if he was going to kill men confined in prison.” “They called him a damned coward [and said] they would never elect him Captain again,” Daniels told Lamborn.

In the pamphlet, Daniels added a few choice details to the scene at the jail. He wrote that Joseph actually killed one of the mobbers, and that defendant Levi Williams directed the assault from atop his horse. “Rush in!” Williams shouted, “There is no danger, boys—all is right!” As the wounded Joseph tumbled out the jailhouse window, Daniels recalled Williams heaping on more brimstone: “Shoot him! God d—n him! Shoot the d—d rascal!” Inconveniently, on the witness stand Daniels said that he did not see Aldrich, Sharp, or Davis at the jailhouse melee. He did say that the guards were firing blanks, although he came by this information secondhand.

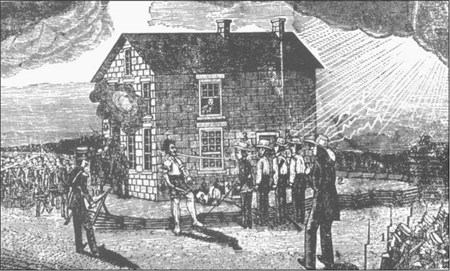

An illustration from William Daniels’s 1844 pamphlet “A Correct Account of the Murders of Generals Joseph and Hyrum Smith”

Credit: Community of Christ Archives

But Daniels had saved his most fantastical imaginings for last. He claimed that a young man lifted Joseph’s prostrate body off the ground and propped it against the waist-high wooden wall surrounding the jail’s well. The ruffian, “bare-foot and bare-headed, having on no coat—with his pants rolled above his knees, and shirtsleeves above his elbows,” muttered:

This is Old Jo; I know him. I know you, Old Jo. Damn you; you are the man that had my daddy shot.

Supposedly the “savage” was the son of Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs, the target of Porter Rockwell’s assassination attempt.

Daniels was just warming up.

With Joseph’s body slouched against the well curb, Levi Williams supposedly assembled four men to shoot the wounded prisoner at point-blank range. While the mobbers primed their muskets and raised the barrels to eye level,

President Smith’s eyes rested upon them with a calm and quiet resignation. He betrayed no agitated feelings and the expression upon his countenance seemed to betoken his only prayer to be, “O, Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

The mobbers fired, and Joseph’s body pitched forward.

Suddenly the ill-clad ruffian returned to the scene, now armed with a bowie knife. He lifted his arm, with every intention of severing Joseph’s head,

. . . when a light, so sudden and powerful, burst from the heavens upon the bloody scene (passing its vivid chain between Joseph and his murderers,) that they were struck with terrified awe and filled with consternation. This light, in its appearance and potency, baffles all powers of description.

The dazzling light stayed the hand brandishing the bowie knife. The soldiers dropped their muskets “and they all stood like marble statues, not having the power to move a single limb of their bodies.”

In his written account, Daniels said the miraculous illumination had converted him to Mormonism, which in turn prompted the mountaintop visitation from Joseph.

Lamborn knew that the heavenly light story would be catnip for the defense, so he homed in on that supernatural detail: You didn’t actually write that pamphlet with your name on it, did you?

No, Daniels answered. The publisher Lyman Littlefield wrote the pamphlet, “though I suppose he got it from what I told him,” Daniels allowed. “I suppose it will astonish you to tell you that I saw a light,” he added.

Other books

Wine of Violence by Priscilla Royal

Serere by Andy Frankham-Allen

A Hundred and One Days: A Baghdad Journal by Asne Seierstad, Ingrid Christophersen

Fate of the Jedi: Backlash by Aaron Allston

Billie Jo by Kimberley Chambers

Sketches from a Hunter's Album by Ivan Turgenev

Winter (Rise of the Pride, Book 2) by Theresa Hissong

The Forest Bull by Terry Maggert

The Storm by Margriet de Moor

The World is My Mirror by Bates, Richard