American Eve (16 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

Evelyn also enjoyed his candid manner and ready laugh: “He was a compendium of information on all subjects, likely and unlikely. He was an authority and teacher. . . . [He] suggested his own genius by his appreciation of genius both contemporary and past.” He was, she writes, one of those men “gifted by Nature beyond the average,” and her growing impression of him, which her mother had felt immediately, was that “he was very kind, and that he was safe. True, he wasn’t the ‘romantic’ type, but he was handsome in a way that appealed, a charming, cultured gentleman whose magnetism undid all my first impressions of him. He emerged as a splendid man, thoughtful, sweet, and kind; a brilliant conversationalist and an altogether interesting companion.”

Numerous other men, most of them frequent patrons of

Florodora,

had already tried unsuccessfully to attract Evelyn’s attention. Some anonymously sent uninspired bouquets or paltry boxes of candy; others, like a Mr. Munroe, sent weekly mash notes, all of which she ignored. As several weeks went by, it was clear who dominated Evelyn’s thoughts. She spoke incessantly with her mother of White and his engrossing lifestyle. She repeated like a mantra the list of guests and the variety of food he had at his splendid parties, which she now attended frequently and where, among others, she met everyone from Annie Oakley to Caruso.

It pleased Evelyn that when it came to Mr. White, her mother’s conversation was equally filled with superlatives. The only one, it seemed, who wasn’t a fan of Stanford White was Mr. James Garland.

Although Mrs. Nesbit, not wanting to close any gates of gilded opportunity, had continued to allow Garland to provide Sunday entertainment on his “floating palace” for her daughter and her, her preference for White, whose generosity seemed limitless, was clear. And, just as Mamma Nesbit began to ponder what to do about the other married millionaire in Evelyn’s life, Garland himself brought up the subject. After Evelyn casually mentioned having attended a Stanford White soirée, Garland’s face clouded over.

“If you continue to associate with Mr. White, we must end our relationship, ” he said, as if scolding her.

An astonished Evelyn, who never considered that the elderly Garland had more than a sociable interest in her (and who she figured at the time was interested in a romantic relationship with her mother), listened as he continued, “I have most serious intentions regarding you. Right now I am divorcing my wife . . . but if you insist on going with a man like White, I cannot see you again.”

Evelyn was flabbergasted, and gave a little nervous laugh, hoping that her mother would know what to say. Her mother said nothing.

“Why?” a puzzled Evelyn finally asked.

“Because,” said Garland with disdain, “he is a voluptuary.” Evelyn didn’t know what the word meant, but she did know that White’s personality and gay parties were infinitely more appealing than anything Garland had to offer, yacht or no yacht. Moreover, if there had been some understanding, unspoken or otherwise, between Garland and her mother regarding Evelyn’s future, the little Spanish maiden had never been let in on the negotiations. Impressionable but precocious, if she gave any thought to the subject of marriage at all, Evelyn invariably considered it a dead end and a trap. She had exhibited no desire to trade the stage for a cage, gilded or otherwise, and when considering Garland specifically, as she put it, “I would as soon have married Santa Claus.”

So, with her mother’s unspoken approval, Evelyn left the rueful James Garland high and dry. He told Evelyn when they reached the dock to let him know if and when she ended her association with White. (The fact that Evelyn would be named in Garland’s divorce suit provided great fodder for the prosecution during the murder trial.)

It is not surprising that a freshly captivated Evelyn saw in White, however unconsciously, a man like her father, who was attentive, irresponsibly fun-loving, and “extremely clever.” As Evelyn put it, “Let me say here that cleverness in a man or woman has always been the supreme attraction.” And just as White had an impressive arsenal of wit at his disposal, his special influence in the Broadway district was additionally attractive to the aspiring actress. Here was someone who could help the stage career he vigorously encouraged, which Garland had obliquely disparaged. And, to put the vanilla ice cream on the cherry pie, Mr. White, who had a wife and family with whom he seemed decidedly contented, was “safe.” But if White was out of the ordinary, so too was the little girl from the suburbs of Pittsburgh who was not the type to take pleasure in the mere commonplace or the placid when offered the incomparable.

On their next luncheon date, Evelyn and White repeated the first afternoon’s harmless uplifting entertainment with a session on the red velvet swing. As Evelyn rode the swing, a disaffected Elsie Ferguson, who had again accompanied her, stood by, wanting to preserve a more genteel image. Like Edna Goodrich, Elsie was unaware that White preferred Evelyn’s unsophisticated vitality. Then, while getting ready to push her again, White commented on the fact that Evelyn had not gotten her teeth fixed. She had no sufficient answer for him, saying simply that Edna had not moved to help her when they were at the dentist’s office, nor did Evelyn or her mother consider it a priority.

White, however, decided to take the issue up directly with her mother again. He assured Mrs. Nesbit that as an artist, his interest in her daughter’s appearance was “a purely aesthetic urge,” and won her over to the idea more easily than her daughter, who had the same aversion regarding a trip to the dentist that most people have (particularly in those days of primitive foot-powered low-speed drills and sickly-sweet laughing gas administered via an ill-fitting, smothering rubberized mask). Mrs. Nesbit found herself “overwhelmingly grateful” for White’s attention to her daughter, since they were too poor to afford the impossible luxury of such a visit. In less than a fortnight, Evelyn had her teeth worked on. She was now perfect.

THE BIG BAD WOLF

As Evelyn would gradually learn, White’s modus operandi was always the same when it came to meeting his next conquest. He would invariably have a current favorite, an old friend, or his secretary, twenty-six-year -old Charles Hartnett, set up a rendezvous with a potential lust interest in one of his “snuggeries,” usually at his studio apartment on Twenty-fourth Street or in the Tower studio at Madison Square Garden. Some of his accomplices were girls who had gotten too old—having passed eighteen; these were “innocent agents” who simply did his bidding, not realizing that they were helping usher the way for their own replacement. Others who worked on White’s behalf “may have been of a less innocent character,” Evelyn later surmised. Needless to say, White was anxious to keep his various “friends” “separate and distinct,” absurdly so it seemed to a naive Evelyn at first. Once, when he invited her to a luncheon at his Twenty-fourth Street studio, where a second girl would be waiting, White cautioned Evelyn in the cab not to let the girl know about his acquaintance with Edna Goodrich. Evelyn giggled and enjoyed the fact that she was chosen to be the keeper of his “silly secrets.” To Evelyn, her mother, and the wider audience, the little chorus girl was his unofficial ward and he her sainted patron.

As Evelyn would describe on the witness stand, “men like White, the baser White with which the world is better acquainted, reduce their methods to an exact science.” The formula never varied. With an appearance and manner that easily deceived them, Stanford White found easy pickings in young “peaches” and “tomatoes” eager to appear on the stage. He insinuated himself into their usually deprived lives, and engaged their mothers (those who had them) as willing or clueless conspirators. Setting himself up as benefactor and friend, White would eventually arrange a meeting out of the public eye. Even if by nature he was a kind man, the

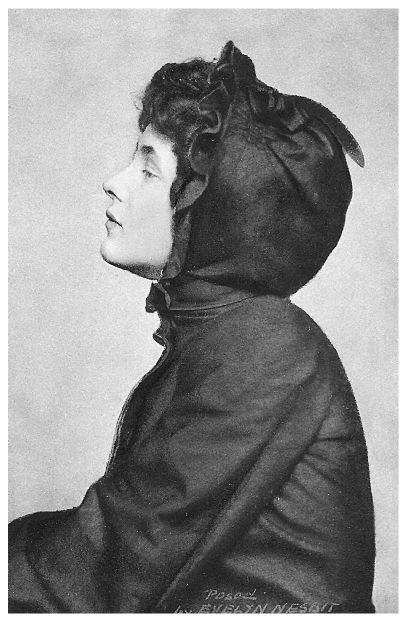

Sixteen-year-old Evelyn wearing Stanny’s

gift of a Red Riding Hood cloak.

fatherly attitude White showed toward those he had “marked down” was, as Evelyn came to see, calculated. A later editorial from the

Atlanta News

that labeled him as monstrous libertine also described how this “brilliant architect . . . was relentless and irresistible in his organized and well-prepared search for the honor and virtue of the young uncorrupted girls of the great metropolis in which he lived.”

With Evelyn, White took the “shortest cut to [her] affections,” both of which were intimately tied to her abbreviated childhood. In addition to her unmistakable love of sweets and food in general, it had become a well-known joke among the theater crowd that “the Kid” loved automata, the mechanical toys she lingered over in the shop window below White’s apartment. So White furnished his life-sized dolly with a new toy each time she visited. She had her pick of anything she fancied in the FAO Schwarz window, an inoffensive and ironic front for White’s hideaway. Nor did her mother consider these relatively expensive gifts of toys as anything but paternal kindness.

During the first impulsive month when he was actively pursuing Evelyn, White revealed himself to her as a man of tremendous powers and capabilities, one of which, unbeknownst to her, was the ability to juggle the affections of numerous girls simultaneously. But as far as Evelyn was concerned, he was a unique man, “large and generous in his dealings with his fellows; brilliant as an artist and scholar; kindly to a degree in his relations to those who needed his kindness.” And in a culture where the norm regarding meals and food in general (even in 1901) was to “buy it, boil it, bolt it and beat it,” White was a connoisseur and gourmand of the “Continental model,” a man who took the act of eating as seriously as he did his art. With variety of taste and sensuous presentation as his foundation, White strove to make meals an aesthetic experience; whether it was teal and mallard or veal medallions and rack of lamb, his table was invariably a source of unending pleasure and an epicurean delight. It was a rule that applied to virtually everything in his life, especially his craving for mignon of a very particular type.

One day when she told White about the artists she had already posed for, he replied that they were all “old stuffs” and that he would introduce her to some real artists, including the foremost illustrator of the day, Charles Dana Gibson. As she would later write in regard to first seeing Stanford White, “he himself looked like an old stuff; at that point in one’s life, anyone over twenty-five seemed ancient.” For their next few meetings it was always the same. White never approached Evelyn directly himself; instead, he had her brought to him by other showgirl acquaintances. These clandestine meetings were well orchestrated, carefully planned down to the last detail, as one might expect from an architect whose own appetite for both fine and unrefined gratification and pursuit of perfection would ultimately be his downfall.

Her benefactor, as her mother now preferred to call White, began to send flowers regularly, while nearly every other day the aged Mr. Clarke, who was also apparently fascinated by Evelyn and moved by her constrained circumstances, sent huge baskets of fruit to her boardinghouse address. As she remembers it, she and her mother were appropriately grateful for this show of “polite attention.” Going beyond what most would consider polite attention, however, White’s next impressive act was to move daughter and mother (and Howard when he was well enough to be “in town”) into the Wellington Hotel, where their accommodations included a drawing room, alcove, and private bath.

The apartment at the Wellington, decorated by the great man personally, was a shrine to sensuality. The color scheme was an enchanting snow white and rose red, a deliberate choice by White to appeal to his little maiden’s love of fairy tales. Her bedroom had white satin walls, red velvet carpets, a huge white bearskin on the floor, ivory white furniture, and a bed draped in ivory satin, covered with rare imported Irish lace. The canopy of the bed was also draped in white satin, “ending in a huge crown from which protruded five thick white ostrich plumes.” In imitation of the red velvet swing room in White’s own apartment on Twenty-fourth Street, the small living room was done in forest green, decorated with swan planters, concealed lights, and a beautiful ebony piano. White also generously engaged a German piano teacher so that Evelyn could revive her piano lessons, for which she rewarded him by studying Beethoven, “especially to please him.”

One day soon after the move, a package arrived for White’s “protégée” containing a sage green hat, a soft green feathered boa, and a gorgeous English-tailored cloak of “an intriguing shade of American beauty red with long flowing lines and a boyish satin collar.” With it came instructions that Evelyn was to wear the cape to a party that Friday night. Rather than become alarmed or suspicious that perhaps White had more than a philanthropic or avuncular interest in Evelyn, Mrs. Nesbit made her daughter a new dress especially for the occasion, and in record time.

The night of the party, she sent it on to the theater. After the performance, Evelyn was told by a stagehand that a carriage was waiting for her on the side of Twenty-ninth Street. As she approached, Evelyn saw that several carriages were waiting there (she wasn’t the only chorus girl being wooed by the captains of industry and Champagne Charlies of Manhattan). Before she could inquire which one was hers, out from the dimness of the greengrocer’s doorway across from where the line of carriages waited stepped White. He got into the carriage with Evelyn.