American Eve (12 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

However, Florence Evelyn’s disenchantment with the alternately mind-numbing and grueling life as studio, advertising, and photographer’s model forced the issue to what would be the next obvious step. Having lived for half a year on the boisterous fringes of the Gay White Way, which shared its sketchy but enticing borders with a number of the studios where she worked, the impatient teen declared to her mother with appropriate histrionics, “I am going to be an actress!”

As young and inexperienced as she was, Florence Evelyn tried to reassure her mother that she could maintain a sensible perspective about her prospects of becoming an actress. She writes in 1934 that she was not stagestruck in the common sense, even though she did have the enthusiasm of every teenage girl whose “desire for the enlargement of life” sees no possible flaws in such an impetuous plan. As far as Florence Evelyn could see, being on the magical stage, where she could woo an audience full of living, responsive people, was a vast improvement over the decidedly mundane studios populated by dismally sedate artists, many of whom were on the far edge of “decrepitude.” And, in addition to living in such close proximity to the theater district, having already had her picture featured in several theatrical magazines, the celebrated girl model was convinced that she could be “supremely indifferent” to the position she might occupy in the spotlight. As she described it years later, she only wanted to be “in it” and see what else the world had to offer her. And, unlike other girls, for whom the stage would be their first exposure to an admiring or appreciative audience, Florence Evelyn already knew the effect she exerted over people with a mere look or the upturn of her chin.

For several weeks, mother and daughter seesawed over the idea of her acting. As Evelyn describes it in one memoir, her mother never really stood a chance with her when she wanted something badly enough. After some inquiries, Mamma Nesbit discovered that her daughter could still pose by day and appear on the stage by night (just as she had worked all week at Wanamaker’s and posed on weekends in Philadelphia). And so Mrs. Nesbit’s attitude changed. Whether or not Florence Evelyn saw this too-familiar arrangement as an utterly unhappy alternative, she convinced herself that she could see her mother’s point about the more practical side of having two careers—again: “the very material fact that . . . stage life would enable me to make a double income.”

If this meant continuing in the alternately suffocating and chilly studios all day, depending on the season, it was the price she had to pay since, as her mother constantly reminded her, the “dollars counted horribly. ” In the end, the combination of Florence Evelyn’s pie-in-the-sky persistence and her mother’s unrelenting hand-wringing about money proved to be deciding factors. One can’t help but sense an undercurrent of desperation in the adult Evelyn’s recollections about this decision, which imply that she was more anxious to distance herself from the grim specter of poverty than she was eager to sustain two simultaneous careers again at such a relatively immature and vulnerable age.

“Fate,” however, as she wrote, “was moving me inexorably in the direction I was to take.”

But not everyone was pleased at this proposed shift in the focus of her still unformed professional life. Neither Frederick Church nor Carroll Beckwith approved, and when Evelyn told the much-admired Beckwith during a modeling session of her intentions to pursue a career on the stage, he exploded in anger, scolded her, threw down his brush, and paced up and down his studio.

“That is preposterous!” he said. “I don’t approve. You are barely sixteen—still a child!”

But instead of showing appreciation for the painter’s paternal concern, a petulant Evelyn balked at his characterization of her as a child and silently fumed throughout the session. She fared no better with the avuncular Church, whose more gentle insistence also focused on her inexperience and youthful vulnerability; at his urging she came close to abandoning her thoughts of the stage, because, as she remembers it, “he lent art a meaning that made deserting it seem like a sacrilege.”

THE BABY FARM

Over the course of several months early in 1901, Florence Evelyn had received a number of letters from a Mr. Marks, a well-known and legitimate theatrical agent who promised in illegibly scribbled letters the req-uisite

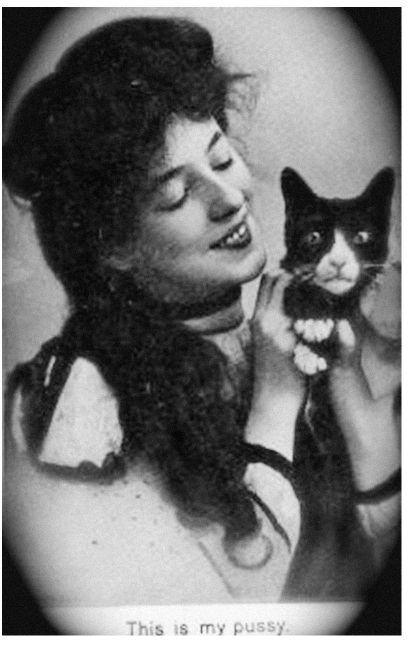

Double-entendre postcard image of Evelyn from her

Florodora

days.

fame and fortune. With no knowledge of the business of Broadway and no ability to discern a genuine from an insincere offer, Mrs. Nesbit and her daughter initially paid little attention to these letters. However, when Marks wrote again in May, saying that he could arrange an introduction to John C. Fisher, the manager of the

Florodora

company, the curtain lifted.

Just as things Oriental had found their way into the popular culture and marketing of the day, so had the Philippines, newly accesible because of the Panama Canal.

Florodora,

a “spicy little musical dish,” was the most popular show on Broadway. Playing nightly at the Moorish Casino Theatre, nicknamed the “temple of feminine pulchritude,”

Florodora

was set in a mythical Philippine Island.

There is little doubt that in spite of Florence Evelyn’s attempts to paint her mother’s initial reaction as anxious and reluctant to have her go on the stage, it didn’t take long for Mrs. Nesbit to rethink her position. To hear Evelyn tell it in 1934, “I overruled my mother’s objections and went with her one day to Mr. Fisher’s office.”

The well-publicized fact that several former

Florodora

soubrettes had managed to snag millionaire husbands may have also factored in the final equation for Mamma Nesbit’s about-face.

Manager Marks met them at the theater. His flamboyant dress— the requisite black derby, black-and-white-checked suit, and diamond-studded bully-boy red tie—struck Mrs. Nesbit as “vulgar.” Sixteen-year -old Florence Evelyn, however, thought it was “spiffy.”

When they entered the office, Marks immediately began to pitch his newest find. Fisher held up his hand and took his partner Riley aside. Fisher then approached Mrs. Nesbit and asked about her qualifications for the chorus, mistaking the girl’s mother as the one who had come for the audition. Marks let out a laugh as Florence Evelyn jumped up from her seat and declared that she was the one who wanted the job. Fisher looked over the five-foot-nothing girl in her homemade skirts, with her hair tied behind her and no makeup.

“So, you want to be an actress?” he asked with mock solemnity.

He turned to her mother.

“Madame, I’m not running a baby farm!”

He went on, explaining that even if he were willing to snatch her from the cradle and allow this little miss to join the company, Comstock’s Gerry Society (which focused specifically on child labor) would be at his door, flaming swords of decontamination drawn and warrants in hand before you could say Diamond Jim Brady. Comstock, with the aid of the district attorney’s office, had of late been stepping up his efforts to crack down on underage children working adult jobs in “depraved environments. ” The theater of course was a particularly sensitive area with Comstock, who saw the entire theater district as an “open sore” spreading filth in the streets. To Comstock, its unsavory atmosphere lured unsuspecting young girls from their homes with promises of overnight success and untold wealth, only to infect them and to have them end up, as he was quoted in one newspaper, “bejeweled Bathshebas, besotted, bedeviled, broken-hearted or brothel-bound.”

Although Fisher smiled condescendingly at her, a devastated Florence Evelyn broke into instantaneous and very real tears. She looked at her mother in desperation, but Mrs. Nesbit returned an equally distressed look.

“All right,” said Fisher, unable to resist the girl before him, whose wholesome, unpainted face was so striking against her dark mass of hair. “There is a rehearsal going on upstairs.” He offered to let her take a look at it, and in less than thirty minutes, the specter of the Gerry Society seemed to have vanished from the producer’s mind, displaced no doubt by thoughts of what an impact this unusually beautiful girl would make in his company. He asked her if she knew how to dance.

“A little,” she replied, suddenly shy and somewhat apprehensive, her dancing (as well as singing and piano) lessons having been abruptly ended back in Pittsburgh when her father died. A woman who played the piano was sent for. Florence Evelyn did an impromptu dance, and offered that she could carry a tune as well.

“The stage manager was keen on my coming into the theater,” the adult Evelyn recalls, but Fisher was less than enthusiastic and said he would “let them know.” It was not because he thought the girl lacked enough talent to fill an anonymous spot in the chorus. If anything, he speculated that she might be a “find.” The real issue was her age. He took Mrs. Nesbit aside and told her frankly that her daughter’s only chance of joining the company was to “be a little reticent” about her real age. If she did this, he would be willing to give her a trial, even though her diminutive figure, thin, narrow shoulders, and perfectly smooth face indicated someone only playing at adulthood—and not very convincingly. Mrs. Nesbit offered no resistance. The very next morning, the first day of a month of rehearsals began for the model turned chorus girl while her mamma attempted to juggle her schedule of modeling appointments to accommodate the rehearsals.

By the end of the month, the former stock girl was a

Florodora

chorus girl. Because of her luxurious brunette hair and sultry eyes, she was cast as an unnamed “charming Spanish maiden.” Putting on costumes and makeup, spending hours doing repetitious actions, being directed to look a certain way or strike a certain pose was nothing new to her. She had learned from the business end of the so-called glamour of the studios, and now, somewhat to her disappointment, she would get the same view of the stage.

When thinking back on this first phase in her theatrical life, Evelyn recalls that her initial reaction to the general shabbiness and banality of the reality of life in the theater did not dampen her enthusiasm completely. Her heart rose at the prospect of being onstage. And, as she already had in other ways in her short life, she quickly dropped her illusions and accepted the machinery of the whole enterprise, the long hours of hard work, and the frequent run-down state of the sets, where “a beautiful garden from the front of the house is drab, tattered and discolored close up,” and “lovely dresses as seen from the auditorium are too often bedraggled and soiled upon close inspection.” Even if the reality of the theater was a “bare, cold barn of a floor, inexpressibly dull when seen in the unromantic light of morning,” and knowing that hers would be an insignificant part, Florence Evelyn prepared herself with juvenile high spirits. Anxious to perfect herself for her anonymous part, the girl considered the world she was about to enter as a “terra incognita” with the promise of novel and exciting rewards all its own.

While the other chorus girls went backstage after their number to the communal dressing room, Florence Evelyn would stand in the wings and watch the featured sextet “dancing gracefully . . . and wonder a little ruefully whether [she would] ever be tall enough or skillful enough to do the work they were doing. . . .” As she writes, “in my innocence I regarded them as the most wonderful part of the show, and, certainly the best paid.” For the girl who, until recently, always seemed to just barely keep her family’s head above the bog of insolvency (if one were to believe her mother), the evidence of the sextet’s success was, for her, the beautiful clothes and jewels they wore offstage. While performing in their wedding-cake gowns, with seven layers of lace like strawberry icing, their long throats decorated with black velvet chokers and wearing long black gloves as they clutched pink parasols, the sextet seemed the height of smartness and elegance to the girl from Allegheny County. Their signature number, “Tell Me Pretty Maiden,” was the highlight of the show each night and frequently the cause of a standing ovation by enthusiastic audience members—predominantly male—before the number was even completed.

Each night, as the dapper, clean-shaven, square-jawed Gibsonish men in their gray cutaway coats, black silk top hats, and pearl gray gloves got down on their knees to serenade the six buxom, statuesque

Florodora

beauties, the audience clapped with delight, waiting for the response to the question “Are there any more at home like you?” And every night a new cordon of stage-door Johnnies then went to wait outside to find out.

While appearing in the show, the youngest member of the company was billed as Florence Evelyn. Her constant primping and preening, however, caused her to be christened “Flossie the Fuss” by the cast and crew. After weeks of teasing, the fledgling chorine considered giving herself a

nom de théâtre

to go with her new career, one that she hoped would put an end to her unwelcome nickname. Two months and a day later, “Flossie the Fuss” disappeared when Florence Evelyn insisted that her new name was Evelyn Nesbit. Another perhaps unintentional but no less compelling reason may have been to assert herself and coincidentally usurp her mother. If there was going to be an Evelyn Nesbit, she would be it. So she dropped Florence for good (although her mother and the family back in Pennsylvania continued to refer to her as Florence). Her mother said nothing.