American Eve (4 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

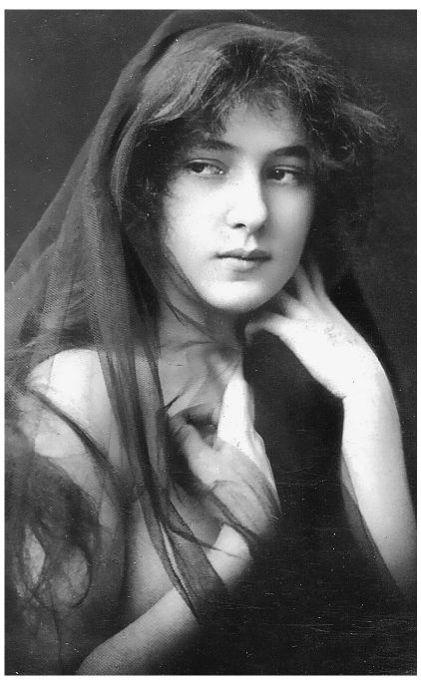

British postcard photograph

of sixteen-year-old Evelyn, 1901.

Five-year-old Evelyn with Pittsburgh playmate.

CHAPTER TWO

Beautiful City of Smoke

Sentimentality is as much out of place in an autobiography as it would be in a time-table or phone book.

—Evelyn Nesbit, My Story

In spite of marked improvements in diagnoses, triage, and treatment, due ironically to the unimaginable carnage of the War Between the States only twenty years earlier, medicine was far from being a sophisticated or reliable science, even as America advanced steadily upon the twentieth century. The average life expectancy was only forty-nine for men and fifty-one for women, and the infant mortality rate was distressingly high, as was the number of deaths of mothers and/or infants during childbirth. People of every age died with awful and chilling regularity from cholera, consumption, pneumonia, diphtheria, typhus, and small-pox, while infants and children died routinely from illnesses such as scarlet fever and whooping cough.

Yet as a light snowfall muted the slate grays and dingy browns of the landscape in and around Tarentum, the girl known as Florence Evelyn Nesbit was born on December 25. Fortunately, against significant odds, there were no complications for either mother or daughter. Those would come about sixteen years later.

The year was 1884. Or perhaps 1885, depending on whose version one takes into account. Over the years, Mrs. Nesbit lied about her daughter’s age so many times to accommodate assorted and potentially sordid circumstances that her selective memory meant that eventually even her daughter couldn’t be 100 percent certain of her own age. As Evelyn relates in several letters, an unfortunate fire consumed all records in her hometown. As a result, verifying her age in order to qualify for social security posed a problem in her later life, which her daughter-in-law remembered as well. When pressed by reporters during her daughter’s rise to fame, however, Mamma Nesbit was nevertheless pretty certain that Florence Evelyn made her debut in an even-numbered year.

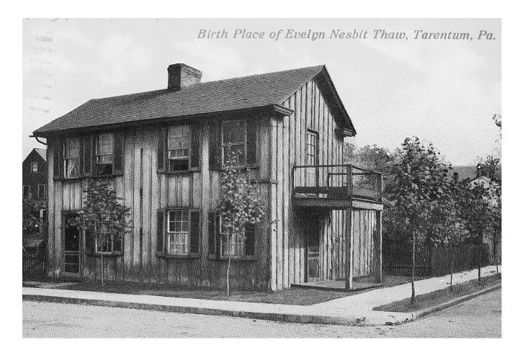

The place we know for sure was Tarentum, located twenty-four miles up the Allegheny River from the steel-driven city of Pittsburgh, which at the time had the dubious distinction of being named the “dirtiest city in America.” Those unfortunate enough to have to scrape out a living in the deep choking cramp of the steel mills and coal mines were also forced to inhabit ramshackle row houses that weren’t much better than the dark holes they toiled in for pennies a day. They were, however, only a cobblestone’s throw (if one had a good arm) from the sprawling suburban estates and magnificently manicured lawns of several of Pittsburgh’s brand-spanking -new Millionaires’ Rows, whose imposing mansions and mock-English gardens sat podgy and stodgy and secure behind colonnades of trees, enormous boxwood hedges, and decorative gilded gates. Their impressive occupants were looked upon as emblems of progress, with eighty-room summer “cottages” in Newport and seats on the New York Stock Exchange. They viewed their world through steel-colored glasses and saw Pittsburgh as “the beautiful city of smoke,” while those who actually made progress possible by sweating out a precarious living six days a week, ten hours a day, considered it hell on earth. But, by comparison, on the farthest edges of the panting smoky city, in communities such as Natoria and Tarentum, in Evelyn’s memory the sunny, rustic world of Victorian America lingered like a ripe Anjou pear in Indian summer.

According to Nesbit family legend, little Florence was such an exceedingly pretty infant that she attracted visitors from the neighboring counties for months after she was born. Two years and two months later, the Nesbits’ second child, Howard, was born, physically more frail and congenitally less feisty than his sister, but with the same large soulful eyes and silken brunet hair. As they grew, Howard and the petite Florence were often mistaken for twins. Their heavy-lidded, unwavering gaze gave brother and sister a “constant expression of knowing and amused detachment” often startling to casual observers in children so young. Because of her special Christmas birthday, Florence Evelyn believed that she was destined always to “get twice as many presents as anybody else.”

Her father, Winfield Scott Nesbit, was a man of great heart and small aspirations. Known as Win or Winnie to his family and friends, he was by all accounts a good-looking, soft-spoken, unimposing man named in honor of a fierce and flinty general (whose career stretched from the War of 1812 until the start of the Civil War, when he served briefly as the Union general-in-chief). He was also described as that rarest of animals, an unambitious lawyer, and therefore one to whom money, its acquisition, and its management were not a priority. Her mother, whose maiden name was Mackenzie, was considered a handsome woman with some talent for sewing; not surprisingly, she had been brought up to wish for

Photo postcard of Evelyn’s house in Tarentum, Pennsylvania, circa 1907.

nothing more than to stitch herself securely into the cherished quilt of Victorian domesticity. She was blithely unaware of how the world worked beyond the limited sphere of wife and mother and therefore knew nothing about her husband’s lack of business acumen, wrongheaded investments, or slipshod business practices. What she did know was that her homemade outfits were routinely praised by friends and neighbors who saw them on mother and daughter. Comfortably cosseted by womanly conventionality, the sometimes skittish Mrs. Nesbit nonetheless seemed perfectly content to be the wife of the amiable Win and go along with his plans for his children’s future. Florence Evelyn, unlike the majority of girls in the country, who barely finished grammar school, would go to Vassar College and travel, while Howard would follow in his father’s footsteps and become a lawyer.

For her first ten years (depending on which account one follows), Florence Evelyn’s childhood was ordinary, no different from that of most girls living in seemingly bucolic towns across America at the time. But if, as certain “big city” social critics and hopeful prophets claimed, a sea change in social mores and sensibilities was seeping through the widening cracks of not-so-ironclad Victorianism, the greater part of hardworking, God-fearing Christians throughout America were still living in communities like Tarentum with populations of fewer than 2,500 people.

Like other young girls “from the provinces,” Florence Evelyn went to picnics and spelling bees and attended Sunday school, where she sang in the choir. She fantasized about running off with the traveling circus in the summer, went ice-skating and sledding in the winter, and attended her first Pirates baseball game with her father when she was five. Part princess, part prizefighter, depending on her mood, Florence Evelyn lived for her father’s praise, and he in turn doted on her. Of course as the head of the house and sole wage earner, Win was the central figure in the family and the dominant force in Florence Evelyn’s life.

Unusually progressive about the intellectual capabilities of “the weaker sex,” Winfield encouraged his daughter’s early interest in reading by building a small library at home of her favorite books. The majority were the typical childhood fairy tales and fantasies, such as

Snow White

and

Sleeping Beauty,

with wonderfully vivid illustrations, charming princes, and happily-ever-afters. But Florence Evelyn read anything her father brought home for her, including the

Arabian Nights,

Arthurian legends, Greek myths, and popular dime novels, even though the latter were considered “books for boys.” With pithy titles such as

Ragged Dick, Slow and Sure, Do and Dare,

and

Mark, the Match Boy,

the rags-to-riches stories the little girl read were full of high sentiment and often ludicrous plots that extolled the virtues identified as “pluck and luck.” Their foremost literary proponent was Horatio Alger Jr., who sold more than 200 million copies of his prescriptive fantasies to post-Civil War American dreamers who wanted a blueprint for success. Of course, none of his faithful reading public knew that before he came to New York City, Alger had been run out of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, accused of “the abominable and revolting crime of gross familiarity with boys.”

A vivacious and free-spirited child, Florence Evelyn bounced headfirst into all activities, particularly those she thought would please her father— singing, dancing, drawing, reciting from her books, playing the piano. She began music and dance lessons with her father’s encouragement and practiced in earnest to learn “The Amorous Goldfish” and “Chin, Chin Chinaman” to please him. She knew in her heart that she was her father’s favorite, although Win made a point of always praising both children for their efforts. Her mother, on the other hand, visibly favored Howard, whose sometimes distracted disposition and nervous temperament mirrored her own and threatened to make him into a mamma’s boy. The children often accompanied their mother on visits to various relatives’ farms in the outlying areas of Donnellsville and Allegheny, where young Florence Evelyn’s inherent self-assurance made an immediate and lasting impression on those around her. One cousin remembers a comment her own mother made: she “despaired of Florence ever learning how to milk a cow,” not because it was hard work, but because “the cow took up too much of her space.”

When Florence Evelyn was around eleven, a change in her father’s job meant the family would have to relocate to Pittsburgh. The Nesbits moved into a modest two-story saltbox house unexceptionally similar to the one they had left, and life continued to be pleasantly predictable. The children were enrolled in the grandly named Shakespeare Elementary School, and every day Win went to his offices on Diamond Street in the family’s rockaway carriage, bought “on time” from Sears, Roebuck. But in less than a year, what had seemed like an eighteenth-century sentimental novel turned Dickensian.

At the age of forty, Winfield Scott Nesbit died without warning, of either a brain hemorrhage or virulent spinal meningitis. Since autopsies were not routinely performed, the local doctors were unable to determine the exact cause of death. But the consequences were no less inexorable and devastating for his stunned family. Encumbrances on the modest property left by Win Nesbit cut off virtually every source of income, leaving his inconsolable wife and children broken and broke.

The days immediately following Win’s funeral, paid for largely by a contribution from his side of the family, were heartbreaking. Having seen their father active and happy in the previous weeks and months, at first both children refused to accept the news. Eleven-year-old Florence Evelyn demanded to see him. She threw herself at the locked bedroom door behind which Win Nesbit lay in stale grim silence on top of the bedcovers until his removal for burial. Mrs. Nesbit had thought it best that he be remembered alive, so there would be no final viewing for the grief-stricken children. Instead, their last image of him entailed handfuls of dirt thrown onto a pine box as it was lowered by ropes into the frost-covered ground while neighbors and family friends intoned the clichés of despair and solace. “Here today and gone tomorrow.” “It was God’s will.” “He’s in a better place.” To the children, it was as if their father were nowhere—he had simply vanished overnight into the cold gray cosmos. It was almost unbearable.