American Eve (8 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

As an increasing number of eager painters and illustrators dropped by the studios where “the little Miss Nesbit” worked steadily in the “skylight world” week after week, several commented on the girl’s potential as a professional photographer’s model. The possibility for such a change appealed to the teenager immediately, since she believed that one had to hold a pose only for several minutes for a photograph (she was wrong). And, her mother offered, she could sit for any number of photographers in the same time that she now sat for one artist (she was not wrong).

Not long after the suggestion was made, Ryland Phillips, a Philadelphia photographer who had heard from John Storm about the fetching fifteen-year-old, arranged for her to sit for some photographic studies. Or rather stand. Throughout the session, Phillips had Florence Evelyn lean casually against a wall, clad in a floor-length milky white satin gown, with her hair falling softly to one side. Unlike the painters, who preferred her without makeup, however, the photographer put some eye makeup and lipstick on Evelyn, subtle touches that nonetheless gave her a startlingly more mature appearance. Phillips was extraordinarily pleased by the pictures in which, he said, she resembled “a young Aphrodite.” He managed to have them printed in an art magazine, where they attracted a good deal of attention; they were then reproduced in the Philadelphia newspapers (and once again a year or two later in

Broadway Magazine

).

By late fall, the Philadelphia newspapers had begun reporting on the “strange and fascinating creature” whose face “shows a remarkable maturity of repose, though [she is] no more than fourteen years old.” Although the issue of her correct age was already becoming a topic for debate, as Florence Evelyn’s popularity grew, so did the demand for the privilege of photographing the “rare young Pittsburgh beauty” or capturing her “dazzling allure on canvas.” As one reporter saw it, she exuded an “enchanting combination of youthful innocence and colossal self-possession.” When one of the local shopkeepers on Arch Street remarked casually to the girl that she was going to shake up the new century that was just around the corner, she almost believed it.

As New Year’s Eve 1899 approached and the final weeks of the 1800s

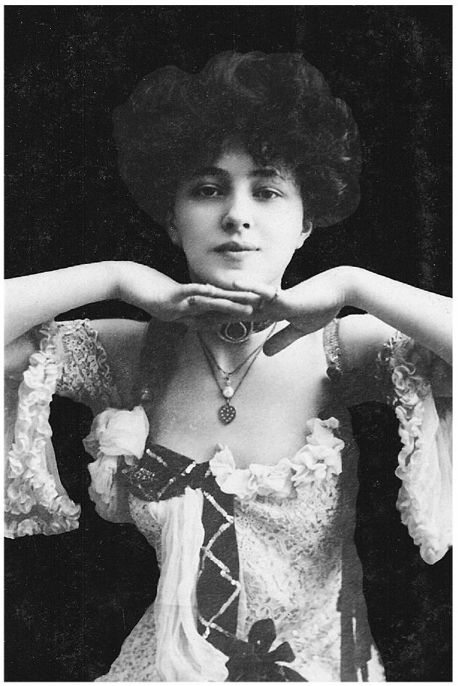

One of the Phillips photographs of fifteen-year-old

Evelyn posing in Philadelphia, 1900.

were peeled away, Florence Evelyn hoped that the much-heralded Century of Progress that was about to unwrap itself would live up to the hoopla and near hysteria she heard on every side. While her mother mulled over the idea of another change in the scenery behind her uniquely photogenic daughter, Florence Evelyn fantasized about how she might figure in whatever awesome changes lay ahead in the pink new tomorrow of 1900 and all tomorrows after that. But not even in her wildest dreams could she have predicted that the public’s burning desire for the perfect emblem of their imagined perfect new age would be realized in a girl from Tarentum. The setting, of course, was already obvious.

Advertising pose of sixteen-year-old Evelyn as the Sphinx.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Little Sphinx in Manhattan

By 1900, questions of identity had become a social obsession. . . . But there was something new: the favored type was one variation or other of the American female.

—Martha Banta, Imagining American Women

Vulgar tradition dictated that portliness in mature men of the dignified leisure class indicated wealth and opulence. The opposite was true for women— dictated to by the useless and expensive canons of conspicuous waste . . . under the guidance of the canon of pecuniary decency, the men find the resulting artificiality and induced pathological features attractive, so for instance the constricted waist.

—Thorsten Veblen

Mrs. Nesbit kept turning over in her head the suggestion that her coveted daughter might have a more profitable career as a photographer’s model in New York City. After a few more turns, despite Florence Evelyn’s regular income posing for a satisfied spectrum of Philadelphia painters, illustrators, and sculptors, in mid-June of 1900, Mrs. Nesbit packed up her few belongings in a ratty carpet bag and set off for New York, alone, with no plan of action whatsoever, leaving her children behind once again. What she did take with her were some letters of introduction to a few well-known metropolitan artists—but she told herself that she would use them only as a last resort. In the meantime, a confused and anxious Florence Evelyn, who, for the first time since her father’s death, had felt a pleasing sensation of security, was pulled off her pedestal and shunted back to Pittsburgh to stay with family friends, while Howard was once more planted on a family farm out in Allegheny from which he had already been uprooted twice before.

As the weeks stretched into months with no money and only a few perfunctory postcards from her mamma, a discouraged Florence Evelyn was alternately bewildered and annoyed. She wondered why she couldn’t have kept working while her mother was away, especially since her mamma took all the modeling money she had earned in the last year and a half to allegedly stir this latest pot of gilt veneer. She wondered where and how her mother was looking for a position. She wondered why the New York artists weren’t clamoring for her services, not knowing that for reasons only she knew, her mamma had felt it necessary to withhold the letters of introduction.

Instead, whether out of fear or sheer ineptitude, Mrs. Nesbit had once again borrowed money from the “good penny,” their ubiquitous family friend Charles Holman, who was making a name for himself back in Pittsburgh, where he had positioned himself to become secretary to the Stock Exchange. At the time, Holman’s continued charity to the little Nesbit family and persistent refusal to let her mother “isolate herself in widowhood” seemed an admirable thing to young Florence Evelyn, who never wondered how it was that her mother managed to communicate with Mr. Holman but not with her or Howard as she supposedly scoured Manhattan for work, month after month.

During one of her last sessions posing, the fetching model had begun to calculate how many hours she needed to work in order to pay back all the people her mother had “unhappily imposed upon” in the last year alone. But it now appeared that the career that had begun so unexpectedly and fortuitously was on the verge of ending just as suddenly. It briefly crossed Florence Evelyn’s mind that in a fit of reactionary perversity, her mother had sabotaged her fledgling career out of jealousy, cutting off her nose to spite her daughter’s prettier face. But at fifteen, all she could do was sit and wait and stare at the walls. And not get paid a penny for doing so.

As of late November, Mrs. Nesbit had not found a job, although it’s anybody’s guess where she looked, how strenuously, and what type of job she looked for in the five months since leaving Philadelphia. But the intensely vibrant, swirling city that offered such glorious opportunities to so many others seemed to wrap itself around Mrs. Nesbit like a winding sheet. Thrown eventually into a state of panic, then paralysis, by the sheer impossibility of it all, with the hatchet edge of winter approaching (if the

Farmer’s Almanac

was accurate), after securing a second-floor, back-room apartment on Twenty-second Street, Mamma Nesbit finally sent for her refugee children. She supposed that if nothing else, they might all find positions at Macy’s department store as they had at Wanamaker’s.

With her sixteenth birthday only three and a half weeks away, an elated Florence Evelyn went alone back to the country on money borrowed from a family friend to reclaim Howard, while a third friend provided the money for the children’s railroad tickets to New York (her mother apparently having spent all of Florence Evelyn’s earnings during her five unaccountable months in Manhattan). The trip from Pennsylvania to Manhattan, however, was far less dismal than the one to Philadelphia a year earlier. Fully revived, Evelyn recalled in later years that on the way to New York she began to foment images of a “splendid future for her and her brother.” Her mother was, noticeably, excluded from that particular vision.

As predicted, winter in December 1900 descended like a sledgehammer. Reunited with her underdressed and overwhelmed children, according to the adult Evelyn, her mother continued to try to look for work as a designer or seamstress. Part of Florence Evelyn still believed (or hoped) naively that in New York City her mother would become a well-known designer, and that their combined efforts would finally pull the family forever beyond the relentless, grappling hands of unfeeling bank presidents, callous courts, and mustard sandwiches. But Mrs. Nesbit’s nebulous efforts proved futile. Everywhere she went, the same questions were asked.

“Have you been to Paris lately?” Or, “Have you had experience with similar firms?”

She had even less success than she did in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, since the impediments that had blocked her way in the other cities were magnified a thousandfold in New York. On the contrary, however, Manhattan offered exceptional head-turning possibilities for an aspiring young model of equally exceptional head-turning looks.

Even though the three Nesbits shivered in a poorly heated room for several days, Mrs. Nesbit maintained her profoundly puzzling and inexplicable inertia regarding the letters of introduction. When it seemed she was on the verge of capitulating, she confessed to Florence Evelyn that she was simply unsure how to proceed. Moreover, she said she was worried about the propriety of her daughter becoming a New York model. Staring at her mother’s vexed expression and empty purse hanging limply on the closet door behind her, the girl asked why it was all right to pose in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia but not New York. Her mother had no answer. A day later, when the all-too-familiar press of insistent hunger squeezed them (each had only a cup of cheap java and a biscuit the entire day), Mrs. Nesbit surrendered.

She took the Ryland Phillips photos and a letter of introduction to James Carroll Beckwith, a well-known and respected New York painter. After seeing the photographs, Beckwith said he wanted to see immediately if this “perfectly formed nymph” really existed in the flesh. The very next day, the diminutive poser and her mother came to Beckwith’s studio on Fifty-seventh Street and Sixth Avenue. The gray-haired artist was instantly struck by what one reporter would describe as “the soul of beauty trapped behind big melancholy eyes.” Beckwith was particularly affected by her haunting pubescent loveliness and the uncommon mixture of innocence and ennui in her expression that others had already noted.

The artist took Mrs. Nesbit aside, spoke to her about the business side of posing, and said that indeed he would be very happy to use her uncommonly lovely daughter as his model. He gave his credentials, in a show of politeness, since it was obvious Mrs. Nesbit had never heard of him and knew nothing of his work or the New York art scene. Florence Evelyn listened intently from the sidelines. When Beckwith mentioned that he taught life classes at the Art Students League, the girl involuntarily gasped and waited nervously for her mother’s reaction.

She had heard about the school while listening to conversations in the Philadelphia studios, and, true to form, when her mother understood that life classes meant “posing in the nude,” she “went to pieces.” Beckwith assured a frantic Mrs. Nesbit that he had no intention of allowing her little girl to pose like that, whereupon, in an uncharacteristic show of proactive involvement, Mamma Nesbit said she would see for herself, since she would be at all the sittings. Within a month, however, she seemed to have forgotten her pledge.

MODELING AND MIGNON

After only ten days in New York, Florence Evelyn was already scheduled to pose twice a week for Beckwith, whose staunchest patron was John Jacob Astor. The elderly painter expressed his concerns for her welfare and took a grandfatherly view of the sweetly inexperienced adolescent with her equally unsophisticated mother, particularly given all the dark and dodgy corners in a city where people whispered nervously about white slavery and the less morally scrupulous routinely sought to procure images popularly known as “mignon.” These were photo postcards of barefoot, fresh-faced young women or girls in Gypsy-style or rural costumes. Only a few degrees of attitude and clothing removed from the more salacious French postcards depicting fully nude

“jeunes filles”

smuggled in from the Continent and circulated throughout the city’s thriving pornographic underground, mignon photos were in some ways more disturbing and subversive, disguising pedophilia as sentiment and pandering to the closeted connoisseur of “young filets.”