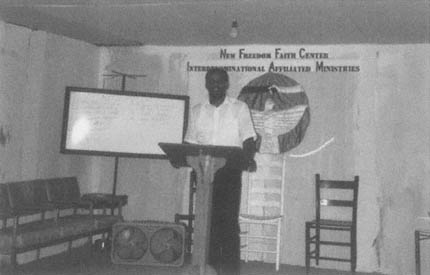

modestly appointed Baptist preacher. He led me around a grassless yard full of car parts, toys and cast-off bits of machinery to show me the sanctuary in which worshipers were "slain in the spirit," spoke in tongues and washed each other's feet. The white walls were virtually unadorned: other decor limited to a lectern, floor fans and a couple dozen unmatched chairs from yard sales.

|

His wife, a pretty, demure woman, invited us into the kitchen and made some hot tea. I wondered what her life was like with him. What did it mean to marry and raise children with a man whose very presence struck spiritual revulsion or fear into most of the community? Yet in their demeanor, the tidiness and discipline of their home, I thought of the spareness of Islam. Another religion that hadn't worked out well with Christianity.

|

Buckley had left the Baptists over a decade ago to become a "two-headed man"like Ricky Cortez, able to see into the futurebecause of his past. In his mid-twenties he had been arrested in Ruston for carrying a stolen gun across the state line to Arkansas. "Guilty as everything," he spent about six months in jail in El Dorado. There, he said, he was like Paul, reading the Bible till midnight and preaching from his cell, getting put in solitary for it, coming out and preaching again. When he was released, a jailer told his mother, "You have a prophet up there."

|

Divine Healing was his way of converting his ability to do "supernatural things, which can either help you or hurt you" to the uses of the Lord. The difference in helping or hurting, to Buckley, "defines the line between Christians and the spiritualists who just do negative work." Around town, his use of oils, herbal potions, special teas and "annointments" with polticeswhat Lorita would have called "cleaning"earned him a tag not only as a two-headed man, but a prophet, root doctor, hoodoo and worse. Hard shells condemned him as a blasphemer, what Sarah would have called a usurper of God's powers, a false magician.

|

|