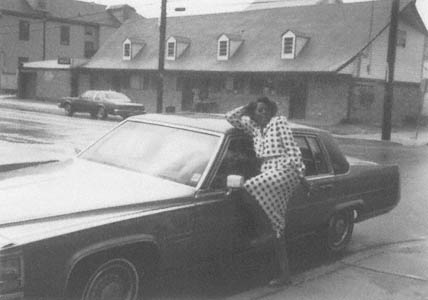

In her loose white short-sleeved blouse and full skirt, white kerchief tied up tight, Ava Kay-as-m'ambo had the same effect on the tour guides as she did on people on the street. Unfortunately, the thick black frames of her glasses gave her away. In the old days, under slavery, an African who had glasses probably used them for reading, and in most of the colonies or Southern states, slaves were not allowed to read. "A hundred years ago I would've been barbecued for coming here to say all this," Ava quipped, pausing at a table next to the lectern to arrange some of the herbs, charms, soaps, books and oils she'd brought. "You know what I'm saying?"

|

The guides chuckled, a little nervously. Probably, they didn't. White, middle-class, mostly retirees, they had signed on as explicators of the French Quarter and this was just part of the educational drill. But they listened. Some tourist was bound to ask about voudou, and this woman in white would make it clear what to say, and there was fresh French roast coffee in china cups.

|

She opened the lecture with a song, a traditional Yoruba chant to Elegba, for Monday was his day. It was a holy rite, but the gulf between the Africanness of what she had to say and the centuries of opposition to that race and everything it stood for made the audience react to the prayer is if it were some kind of mildly embarrassing warm-up act.

|

"Voudou is a way of life," she began, "not just something we do on Sunday," and went on with a brief rundown of the orisha and the cultureuncomfortably revisionist to some, judging from the crossed arms and knowing glances. "I'm a Catholic, toooh, yes," she offered, perhaps to bridge the gap. "My favorite church is Our Lady of Guadalupe, especially the novenas. But I also believe in voudou. And when people ask me what voudou believes in, I say: we serve the same God you serve. We worship the God Force." Arms remained crossed, although many took notes.

|

|