America's Great Depression (13 page)

Read America's Great Depression Online

Authors: Murray Rothbard

Workers, for example, become persuaded of the great importance of preserving the

mystique

of the union: of union solidarity in “not crossing a picket line,” or not undercutting union wage rates.

Unions almost always reinforce this

mystique

with violence, but there is no gainsaying the breadth of its influence. To the extent that workers, both in and out of the union, feel bound by this

mystique

, to that extent will they refuse to bid wages downward even when they are unemployed. If they do that, then we must conclude that they are unemployed

voluntarily

, and that the way to end their unemployment is to convince them that the

mystique

of the union is morally absurd.9 However, while these workers are unemployed voluntarily, as a consequence of their devotion to the union, it is highly likely that the workers do not fully realize the consequences of their ideas and actions. The mass of men are generally ignorant of economic truths. It is highly possible that once they discovered that their unemployment was the direct result of their devotion to union solidarity, much of this devotion would quickly wither away.

Both workers and businessmen may become persuaded by the mistaken idea that artificial propping of wage rates is beneficial.

This factor played a great role in the 1929 depression. As early as the 1920s, “big” businessmen were swayed by “enlightened” and

“progressive” ideas, one of which mistakenly held that American prosperity was

caused

by the payment of high wages (rates?) instead of the other way round. As if other countries had a lower standard of living because their businessmen stupidly refused to quadruple or quintuple their wage rates! By the time of the depression, then, 9It is immaterial to the argument whether or not the present writer believes the

mystique

to be morally absurd.

Keynesian Criticisms of the Theory

45

businessmen were ripe for believing that lowering wage rates would cut “purchasing power” (consumption) and worsen the depression (a doctrine that the Keynesians later appropriated and embellished). To the extent that businessmen become convinced of this economic error, they are responsible for unemployment, but responsible, be it noted, not because they are acting “selfishly” and

“greedily” but precisely because they are trying to act “responsibly.” Insofar as government reinforces this conviction with cajolery and threat, the government bears the primary guilt for unemployment.

What of the Keynesian argument, however, that a fall in wage rates would

not

help cure unemployment because it would slash purchasing power and therefore deprive industry of needed demand for its products? This argument can be answered on many levels. In the first place, as prices fall in a depression,

real

wage rates are not only maintained but

increased

. If this helps employment by raising purchasing power, why not advocate drastic

increases

in money wage rates? Suppose the government decreed, for example, a minimum wage law where the minimum was triple the going wage rates? What would happen? Why don’t the Keynesians advocate such a measure?

It is clear that the effect of such a decree would be total mass unemployment and a complete stoppage of the wheels of production. Unless . . . unless the money supply were increased to permit employers to pay such sums, but in that case

real

wage rates have not increased at all! Neither would it be an adequate reply to say that this measure would “go too far” because wage rates are

both

costs to entrepreneurs and incomes to workers. The point is that the free-market rate is precisely the one that adjusts wages—costs

and

incomes—to the full-employment position. Any other wage rate distorts the economic situation.10

The Keynesian argument confuses wage

rates

with wage

incomes

—a common failing of the economic literature, which often 10Maximum wage controls, such as prevailed in earlier centuries and in the Second World War, created artificial shortages of labor throughout the economy—the reverse of the effect of minimum wages.

46

America’s Great Depression

talks vaguely of “wages” without specifying rate or income.11 Actually,

wage income

equals

wage rate

multiplied by the amount of time over which the income is earned. If the wage

rate

is per hour, for example, wage rate will equal total wage income divided by the total number of hours worked. But then the total wage income depends on the number of hours worked as well as on the wage rate. We are contending here that a drop in the wage rate will lead to an increase in the total number employed; if the total man-hours worked increases enough, it can also lead to an

increase

in the total wage bill, or payrolls. A fall in wage rate, then, does not necessarily lead to a fall in total wage incomes; in fact, it may do the opposite.

At the very least, however, it

will

lead to an absorption of the unemployed, and this is the issue under discussion. As an illustration, suppose that we simplify matters (but not too drastically) and assume a fixed “wages fund” which employers can dispense to workers. Clearly, then, a reduced wage rate will permit the same payroll fund to be spread over a greater number of people. There is no reason to assume that total payroll will fall.

In actuality, there is no fixed fund for wages, but there is rather a fixed “capital fund” which business pays out to all factors of production. Ultimately, there is no return to capital goods, since their prices are all absorbed by wages and land rents (and interest, which, as the price of time, permeates the economy). Therefore, what business as a whole has at any time is a fixed fund for wages, rents, and interest. Labor and land are perennial competitors.

Since production functions are not fixed throughout the economy, a widespread reduction in wage rates would cause business to substitute labor for land, labor now being relatively more attractive

vis-à-vis

land than it was before. Consequently, aggregate payrolls would not be the

same

; they would

increase

, because of the substitution effect in favor of labor as against land. The aggregate demand for labor would therefore be “elastic.”12

11See Hutt, “The Significance of Price Flexibility

,”

pp. 390ff.

12Various empirical studies have maintained that the aggregate demand for labor is highly elastic in a depression, but the argument here does not rest upon them. See Benjamin M. Anderson, “The Road Back to Full Employment,” in

Keynesian Criticisms of the Theory

47

Suppose, however, that the highly improbable “worst” occurs, and the demand for labor turns out to be inelastic, i.e., total payrolls decline as a result of a cut in wage rates. What then? First, such inelasticity could only be due to businesses holding off from investing in labor in expectation that wage rates will fall further.

But the way to meet such speculation is to permit wage rates to fall as quickly and rapidly as possible. A quick fall to the free-market rate will demonstrate to businessmen that wage rates have fallen their maximum viable amount. Not only will this

not

lead businesses to wait further before investing in labor, it will stimulate businesses to hurry and invest before wage rates rise again. The popular tendency to regard speculation as a commanding force in its own right must be avoided; the more astute as forecasters and diviners of the economy the businessmen are, the more they will “speculate,” and the more will their speculation spur rather than delay the natural equilibrating forces of the market. For any mistakes in speculation—selling or buying goods or services too fast or too soon—will directly injure the businessmen themselves. Speculation is

not

self-perpetuating; it depends wholly and ultimately on the underlying forces of natural supply and consumer demand, and it promotes adjustment to those forces. If businessmen overspeculate in inventory of a certain good, for example, the piling up of unsold stock will lead to losses and speedy correction. Similarly, if businessmen wait too long to purchase labor, labor “shortages” will develop and businessmen will quickly bid up wage rates to their “true” free-market rates. Entrepreneurs, we remember, are trained to forecast the market correctly; they only make mass errors when governmental or bank intervention distorts the “signals” of the market and misleads them on the true state of underlying supply and demand. There is no interventionary deception here; on the contrary, we are discussing a

return

to the free market after a previous intervention has been eliminated.

If a quick fall in wage rates ends and even reverses withholding of the purchase of labor, a slow, sluggish, downward drift of wage Paul T. Homan and Fritz Machlup, eds.

Financing American Prosperity

(New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1945), pp. 20–21.

48

America’s Great Depression

rates will aggravate matters, because (a) it will perpetuate wages above free market levels and therefore perpetuate unemployment; and (b) it will stimulate withholding of labor purchases, thereby tending to aggravate the unemployment problem even further.

Second, whether or not such speculation takes place, there is still no reason why unemployment cannot be speedily eliminated.

If workers do not hold out for a reserve price because of union pressure or persuasion, unemployment will disappear even if total payroll has declined.

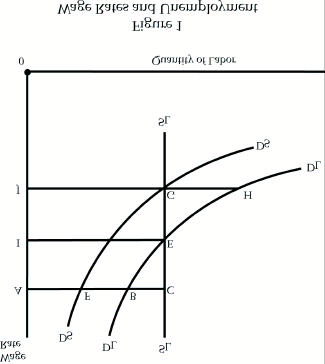

The following diagram will illustrate this process: (see Figure 1).

Quantity of Labor is on the horizontal axis; wage rate on the vertical. DLDL is the aggregate demand for Labor; IE is the total stock of labor in the society; that is, the total supply of labor seeking work. The supply of labor is represented by vertical line SLSL

rather than by the usual forward-sloping supply curve, because we

Keynesian Criticisms of the Theory

49

may abstain from any cutting of hours due to falling wage rates, and more important, because we are investigating the problem of

involuntary

unemployment rather than voluntary. Those who wish to cut back their hours, or quit working altogether when wage rates fall, can hardly be considered as posing an “unemployment problem” to society, and we can therefore omit them here.

In a free market, the wage rate will be set by the intersection of the labor supply curve SLSL and the demand curve DLDL, or at point E or wage rate 0I. The labor stock IE will be fully employed.

Suppose, however, that because of coercion or persuasion, the wage rate is kept rigid so that it does not fall below 0A. The supply of labor curve is now changed: it is now horizontal over AC, then rises vertically upward, CSL. Instead of intersecting the demand for labor at point E the new supply of labor curve intersects it at point B. This equilibrium point now sets the minimum wage rate of 0A, but only employs AB workers, leaving BC unemployed. Clearly, the remedy for the unemployment is to remove the artificial prop keeping the supply of labor curve at AC, and to permit wage rates to fall until full-employment equilibrium is reached.13

Now, the critic might ask: suppose there is not only speculation that will speed adjustment, but speculation that

overshoots

its mark.

The “speculative demand for labor” can then be considered to be DsDs, purchasing less labor at every wage rate than the “true” demand curve requires. What happens? Not unemployment, but full employment at a lower wage rate, 0J. Now, as the wage rate falls

below

underlying market levels, the true demand for labor becomes ever greater than the supply of labor; at the new “equilibrium” wage the gap is equal to GH. The enormous pressure of this true demand leads entrepreneurs to see the gap, and they begin to bid up wage rates to overcome the resulting “shortage of labor.” Speculation is self

correcting

rather than self aggravating, and wages are bid up to the underlying free-market wage 0I.

If speculation presents no problems whatever and even helps matters when wage rates are permitted to fall freely, it accentuates 13See Hutt, “The Significance of Price Flexibility

,”

p. 400.

50

America’s Great Depression

the evils of unemployment as long as wages are maintained above free-market levels. Keeping wage rates up or only permitting them to fall sluggishly and reluctantly in a depression sets up among businessmen the expectation that wage rates must

eventually

be allowed to fall. Such speculation lowers the aggregate demand curve for labor, say to DsDs. But with the supply curve of labor still maintained horizontally at AC, the equilibrium wage rate is pushed farther to the left at F. and the amount employed reduced to AF, the amount unemployed increased to FC.14

Thus, even if total payrolls decline, freely falling wage rates will always bring about a speedy end to involuntary unemployment.

The Keynesian linkage of total employment with total monetary demand for products implicitly

assumes

rigid wage rates downward; it therefore cannot be used to criticize the policy of freely-falling wage rates. But even if full employment is maintained, will not the declining demand further depress business? There are two answers to this. In the first place, what has happened to the existing money supply? We are assuming throughout a given quantity of money existing in the society. This money has not disappeared. Neither, for that matter, has total monetary spending necessarily declined.