Amy, My Daughter (3 page)

Authors: Mitch Winehouse

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #music, #Personal Memoirs, #Composers & Musicians, #Individual Composer & Musician

I knew I shouldn't laugh, but it was so typically Amy. She told me later that she'd sung it to calm herself down whenever she knew she was in trouble.

Just about the only thing she seemed to enjoy about school was performance. However, one year when Amy sang in a show she wasn't very good. I don't know what went wrong â perhaps it was the wrong key for her again â but I was disappointed. The following year things were different. âDad, will you both come to see me at Ashmole?' she asked. âI'm singing again.' To be honest, my heart sank a bit, with the memory of the previous year's performance, but of course we went. She sang the Alanis Morissette song âIronic', and she was as terrific as I knew she could be. What I wasn't expecting was everyone else's reaction: the whole room sat up. Wow, where did this come from?

By now Amy was twelve and she wanted to go to a drama school full time. Janis and I were against it but Amy applied to the Sylvia Young Theatre School in central London without telling us. How she even knew about it we never figured out as Sylvia Young only advertised in

The Stage

. Amy eventually broke the news to us when she was invited to audition. She decided to sing âThe Sunny Side Of The Street', which I coached her through, helping with her breath control, and won a half-scholarship for her singing, acting and dancing. Her success was reported in

The Stage

, with a photograph of her above the column.

As part of her application, Amy had been asked to write something about herself. Here's what she wrote:

Â

All my life I have been loud, to the point of being told to shut up. The only reason I have had to be this loud is because you have to scream to be heard in my family.

My family? Yes, you read it right. My mum's side is perfectly fine, my dad's family are the singing, dancing, all-nutty musical extravaganza.

I've been told I was gifted with a lovely voice and I guess my dad's to blame for that. Although unlike my dad, and his background and ancestors, I want to do something with the talents I've been âblessed' with. My dad is content to sing loudly in his office and sell windows.

My mother, however, is a chemist. She is quiet, reserved.

I would say that my school life and school reports are filled with âcould do betters' and âdoes not work to her full potential'.

I want to go somewhere where I am stretched right to my limits and perhaps even beyond.

To sing in lessons without being told to shut up (provided they are singing lessons).

But mostly I have this dream to be very famous. To work on stage. It's a lifelong ambition.

I want people to hear my voice and just forget their troubles for five minutes.

I want to be remembered for being an actress, a singer, for sell-out concerts and sell-out West End and Broadway shows.

Â

I think it was to the school's relief when Amy left Ashmole. She started at the Sylvia Young Theatre School when she was about twelve and a half and stayed there for three years â but what a three years it was. It was still school, which meant she was always being told off, but I think they put up with her because they recognized that she had a special talent. Sylvia Young herself said that Amy had a âwild spirit and was amazingly clever'. But there were regular âincidents' â for example, Amy's nose-ring. Jewellery wasn't allowed, a rule Amy disregarded. She would be told to take the nose-ring out, which she would do, and ten minutes later it was back in.

The school accepted that Amy was her own person and gave her a degree of leeway. Occasionally they turned a blind eye when she broke the rules. But there were times when she took it too far, especially with the jewellery. She was sent home one day when she'd turned up wearing earrings, her nose-ring, bracelets and a belly-button piercing. To me, though, Amy wasn't being rebellious, which she certainly could be; this was her expressing herself.

And punctuality was a problem. Amy was late most days. She would get the bus to school, fall asleep, go three miles past her stop, then have to catch another back. So, although this was where Amy wanted to be, it wasn't a bed of roses for anyone.

Amy's main problem at Sylvia Young's was that, as well being taught stagecraft, which included ballet, tap, other dance, acting and singing, she had to put up with the academic side or, as Amy referred to it, âall the boring stuff'. About half of the time was allocated to ânormal' subjects and she just wasn't interested. She would fall asleep in lessons, doodle, talk and generally make a nuisance of herself.

Amy really got into tap-dancing. She was pretty good at it when she started at the school but now she was learning more advanced techniques. When we were at my mother's flat for dinner on Friday nights, Amy loved to tap-dance on the kitchen floor because it gave a really good clicking sound. The clicks it gave were great. I told her she was as good a dancer as Ginger Rogers, but my mother wouldn't have that: she said Amy was better.

Amy would put her tap shoes on and say, âNan, can I tap-dance?'

âGo downstairs and ask Mrs Cohen if it's all right,' my mum would reply, âbecause you know what she's like. She'll only complain to me about the noise.'

So Amy would go and ask Mrs Cohen if it was all right and Mrs Cohen would say, âOf course it's all right, darling. You go and dance as much as you like.' And then the next day Mrs Cohen would complain to my mum about the noise.

After dinner on a Friday night, we'd play games. Trivial Pursuit and Pictionary were two of our favourites. Amy and I played together, my mum and Melody made up the second team, with Jane and Alex as the third. They were the âquiet' ones, thoughtful and studious, my mum and Melody were the âloud' pair, with a lot of screaming and shouting, while Amy and I were the âcheats'. We'd try to win no matter what.

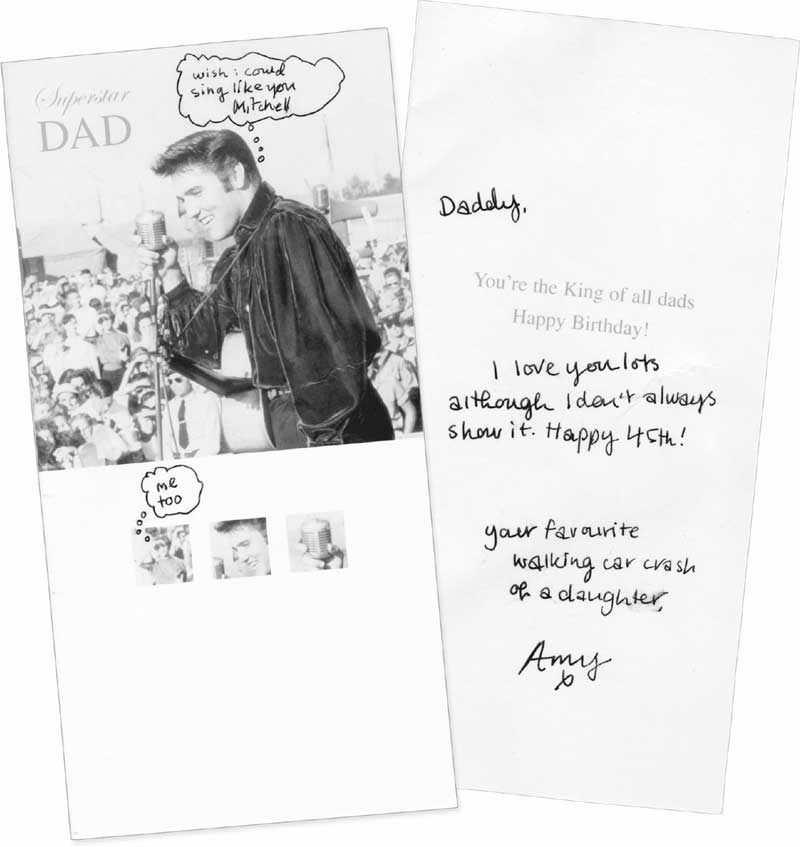

Another lovely birthday card from Amy, aged twelve. This came just after yet another meeting with Amy's teacher about her behaviour.

Â

When she wasn't playing games or tap-dancing, Amy would borrow my mum's scarves and tops. She had a way of making them seem not like her nan's things but stylish, tying shirts across her middle and that sort of thing. She also started wearing a bit of makeup â never too much, always understated. She had a beautiful complexion so she didn't use foundation, but I'd spot she was wearing eyeliner and lipstick â âYeah, Dad, but don't tell Mum.'

But while my mum indulged Amy's experiments with makeup and clothes, she hated Amy's piercings. Later on when Amy began getting tattoos, she'd have a go at her about all of it. Amy's âCynthia' tattoo came after my mum had passed away â she would have loathed it.

Â

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

Â

Along with other pupils from Sylvia Young's, Amy started getting paid work around the time she became a teenager. She appeared in a sketch on BBC2's series

The Fast Show

; she stood precariously on a ladder for half an hour in

Don Quixote

at the Coliseum in St Martin's Lane (she was paid eleven pounds per performance, which I'd look after for her as she always wanted to spend it on sweets); and in a really boring play about Mormons at Hampstead Theatre where her contribution was a ten-minute monologue at the end. Amy loved doing the little bits of work the school found for her, but she couldn't accept that she was still a schoolgirl and needed to study.

Eventually Janis and I were called in to see the head teacher of the school's academic side, who told us he was very disappointed with Amy's attitude to her work. He said that he constantly had to pressure her to buckle down and get some work done. He accepted that she was bored and they even tried moving her up a year to challenge her more, but she became more distracted than ever.

The real blow came when the academic head teacher phoned Janis, behind Sylvia Young's back, and told her that if Amy stayed at the school she was likely to fail her GCSEs. When Sylvia heard about this she was very upset and the head teacher left shortly afterwards.

Contrary to what some people have said, including Amy, Amy was not expelled from Sylvia Young's. In fact, Janis and I decided to remove her as we believed that she had a better chance with her exams at a ânormal' school. If you're told that your daughter is going to fail her GCSEs, then you have to send her somewhere else. Amy didn't want to leave Sylvia Young's and cried when we told her that we were taking her away. Sylvia was also upset and tried to persuade us to change our minds, but we believed we were doing the right thing. She stayed in touch with Amy after she'd left, which surprised Amy, given all the rows they'd had over school rules. (Our relationship with Sylvia and her school continues to this day. From September 2012, Amy's Foundation will be awarding the Amy Winehouse Scholarship, whereby one student will be sponsored for their entire five years at the school.)

Amy had to finish studying for her GCSEs somewhere, though, and the next school to get the Amy treatment was the all-girls Mount School in Mill Hill, north-west London. The Mount was a very nice, âproper' school where the students were decked out in beautiful brown school uniforms â a huge change from leg warmers and nose-rings. Music was strong there and, in Amy's words, kept her going. The music teacher took a particular interest in her talent and helped her settle in. I use that term loosely. She was still wearing her jewellery, still turning up late and constantly rowing with teachers about her piercings, which she delighted in showing to everybody. When I remember where some of those piercings were, I'm not surprised the teachers got upset. But, one way or another, Amy got five GCSEs before she left the Mount and yet another set of breathless teachers behind her.

There was no question of her staying on for A levels. She had had enough of formal education and begged us to send her to another performing-arts school. Once Amy had made up her mind, that was it: there was no chance of persuading her otherwise.

When Amy was sixteen she went to the BRIT School in Croydon, south London, to study musical theatre. It was an awful journey to get there â from the north of London right down to the south, which took her at least three hours every day â but she stuck at it. She made lots of friends and impressed the teachers with her talent and personality. She also did better academically: one teacher told her she was âa naturally expressive writer'. At the BRIT School Amy was allowed to express herself. She was there for less than a year but her time was well spent and the school made a big impact on her, as did she on it and its students. In 2008, despite the personal problems she was having, she went back to do a concert for the school by way of a thank-you.

As it turned out, it was a good thing that Sylvia Young stayed in touch with Amy after she left the school, because it was Sylvia who inadvertently sent Amy's career in a whole new direction.

Towards the end of 1999, when Amy was sixteen, Sylvia called Bill Ashton, the founder, MD and life president of the National Youth Jazz Orchestra (NYJO), to try to arrange an audition for Amy. Bill told Sylvia that they didn't audition. âJust send her along,' he said. âShe can join in if she wants to.'

So Amy went along, and after a few weeks, she was asked to sing with the orchestra. One Sunday morning a month or so later, they asked Amy to sing four songs with the orchestra that night because one of their singers couldn't make it. She didn't know the songs very well but that didn't faze her â water off a duck's back for Amy. One quick rehearsal and she'd nailed them all.

Amy sang with the NYJO for a while, and did one of her first real recordings with them. They put together a CD and Amy sang on it. When Jane and I heard it, I nearly fainted â I couldn't believe how fantastic she sounded. My favourite song on that CD has always been âThe Nearness Of You'. I've heard Sinatra sing it, I've heard Ella Fitzgerald sing it, I've heard Sarah Vaughan sing it, I've heard Billie Holiday sing it, I've heard Dinah Washington sing it and I've heard Tony Bennett sing it. But I have never heard it sung the way Amy sang it. It was and remains beautiful.

There was no doubt that the NYJO and Amy's other performances pushed her voice further, but it was a friend of Amy's, Tyler James, who really set the ball rolling for her. Amy and Tyler had met at Sylvia Young's and they remained best friends to the end of Amy's life. At Sylvia Young's, Amy was in the academic year below Tyler, so when they were doing academic work they were in different classes. But on the singing and dancing days they were in the same class, as Amy had been promoted a year, so they rehearsed and did auditions together. They met when their singing teacher, Ray Lamb, asked four students to sing âHappy Birthday' on a tape he was making for his grandma's birthday. Tyler was knocked out when he heard this little girl singing âlike some jazz queen'. His voice hadn't broken and he was singing like a young Michael Jackson. Tyler says he recognized the type of person Amy was as soon as he spotted her nose-ring and heard that she'd pierced it herself, using a piece of ice to numb the pain.

They grew closer after Amy had left Sylvia Young, when Tyler would meet up regularly with her, Juliette and their other girlfriends. Tyler and Amy talked a lot about the downs that most teenagers have. Every Friday night they would speak on the phone and every conversation ended with Amy singing to him or him to her. They were incredibly close, but Tyler and Amy weren't boyfriend and girlfriend, more like brother and sister; he was one of the few boys Amy ever brought along to my mum's Friday-night dinners.

After leaving Sylvia Young's, Tyler had become a soul singer, and while Amy was singing with the NYJO, Tyler was singing in pubs, clubs and bars. He'd started working with a guy named Nick Shymansky, who was with a PR agency called Brilliant!. Tyler was Nick's first artist, and he was soon hounding Amy for a tape of her singing that he could give to Nick. Eventually Amy gave him a tape of jazz standards she had sung with the NYJO. Tyler was blown away by it, and encouraged her to record a few more tracks before he sent the tape to Nick.

Now Tyler had been talking about Amy to Nick for months, but Nick, who was only a couple of years older than Tyler and used to hearing exaggerated talk about singers, wasn't expecting anything life-changing. But that, of course, was what he got.

Amy sent her tape to him in a bag covered in stickers of hearts and stars. Initially Nick thought that Amy had just taped someone else's old record because the voice didn't sound like that of a sixteen-year-old. But as the production was so poor he soon realized that she couldn't have done any such thing. (She had in fact recorded it with her music teacher at Sylvia Young's.) Nick got Amy's number from Tyler but when he called she wasn't the slightest bit impressed. He kept calling her, and finally she agreed to meet him when she was due to rehearse in a pub just off Hanger Lane, in west London.

It was nine o'clock on a Sunday morning â Amy could get up early when she really wanted to (at this time she was working at weekends, selling fetish wear at a stall in Camden market, north London). As Nick approached the pub he could hear the sound of a âbig band' â not what you expect to hear floating out of a pub at that hour on a Sunday morning. He walked in and was stunned by what he saw: a band of sixty-to-seventy-year-old men and a kid of sixteen or seventeen, with an extraordinary voice. Straight away Nick struck up a rapport with Amy. She was smoking Marlboro Reds, when most kids of her age smoked Lights, which he says told him Amy always had to go one step further than anyone else.

As Nick was talking to her in the pub car park, a car reversed and Amy screamed that it had driven over her foot. Nick was concerned and sympathetic, checking that she was all right. In fact, the car hadn't driven over Amy's foot and she had staged the whole thing to find out how he would react. It was the choking game all over again â she never outgrew that sort of thing. I've no idea what in Amy's mind the test was intended to achieve, but after that Amy and Nick really hit it off and he remained a close friend for the rest of her life.

Nick introduced Amy to his boss at Brilliant!, Nick Godwyn, who told her they wanted her to sign a contract. He invited Janis, Amy and me out for dinner, Amy wearing a bobble hat and cargos, with her hair in pigtails. She seemed to take it in her stride, but I could barely sit still.

Nick told us how talented he thought Amy was as a writer, as well as a singer. I knew how good she was as a singer, but it was great hearing an industry professional say it. I'd known she was writing songs, but I'd had no idea if she was any good because I'd never heard any of them. Afterwards, on the way back to Janis's to drop her and Amy off, I tried to be realistic about the deal â a lot of the time these things come to nothing â and said to Amy, âI'd like to hear some of your songs, darling.'

I wasn't sure she was even listening to me.

âOkay, Dad.'

I didn't get to hear any of them though â at least, not yet.

As Amy was only seventeen she was unable to sign a legal contract, so Janis and I agreed to. With Amy, we formed a company to represent her. Amy owned 100 per cent of it, but it was second nature to her to ask us to be involved in her career. As a family, we'd always stuck together. When I'd run my double-glazing business, my stepfather had worked for me, driving round London collecting the customer satisfaction forms we needed to see every day in head office. When he died my mum took over.

By now Amy had a day job. She was learning to write showbiz stories at WENN (World Entertainment News Network), an online media news agency. Juliette had got her the job â her father, Jonathan Ashby, was the company's founder and one of its owners. It was at WENN that Amy met Chris Taylor, a journalist working there. They started going out and quickly became inseparable. I noticed a change in her as soon as they got together: she had a bounce in her step and was clearly very happy. But it was obvious who was the boss in the relationship â Amy. That's probably why it didn't work out. Amy liked strong men and Chris, while a lovely guy, didn't fall into that category.

The relationship lasted about nine months, it was her first serious relationship, and when it finished, Amy was miserable â but painful though the break-up was, her relationship with Chris had motivated her creatively, and ultimately formed the basis of the lyrics for her first album,

Frank

.

Â

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

Â

Excited as Amy was about her management contract, music-business reality soon intruded: only a few months later Brilliant! closed down. While usually this is a bad sign for an artist, Amy wasn't lost in the shuffle. Simon Fuller, founder of 19 Management, who managed the Spice Girls among others, bought part of Brilliant!, including Nick Shymansky and Nick Godwyn.

Every year Amy's birthday cards made me laugh.

Â

As before, with Amy still under eighteen, Janis and I signed the management contract with 19 on Amy's behalf. To my surprise, 19 were going to pay Amy £250 a week. Naturally this was recoupable against future earnings but it gave her the opportunity to concentrate on her music without having to worry about money. It was a pretty standard management contract, by which 19 would take 20 per cent of Amy's earnings. Well, I thought, it looks like she's going to be bringing out an album â which was great. But, I wondered, who the hell's going to buy it? I still didn't know what her own music sounded like. I'd nagged, but she still hadn't played me anything she'd written. I was beginning to understand that she was reluctant to let me hear anything until it was finished, so I let it go. Amy seemed to be enjoying what she was doing and that was good enough for me.

Along with the management contract, Amy became a regular singer at the Cobden Club in west London, singing jazz standards. Word soon spread about her voice, and before long industry people were dropping in to see her. It was always boiling hot in the Cobden Club, and on one hotter than usual night in August 2002 I'd decided I couldn't stand it any longer and was about to leave when I saw Annie Lennox walk in to listen to Amy. We started talking and she said, âYour daughter's going to be great, a big star.'

It was thrilling to hear those words from someone as talented as Annie Lennox, and when Amy came down from the stage I waved her over and introduced them to each other. Amy got on very well with Annie and I saw for the first time how natural she was around a big star. It's as if she's already fitting in, I thought.

It wasn't just the crowds at the Cobden Club who were impressed with Amy. After she had signed with 19, Nick Godwyn told Janis and me that there had been a lot of interest in her from publishers, who wanted to handle her song writing, and from record companies, who wanted to handle her singing career. This was standard industry practice, and Nick recommended the deals be made with separate music companies so neither had a monopoly on Amy.

Amy signed the music-publishing deal with EMI, where a very senior A&R, Guy Moot, took responsibility for her. He set her up to work with the producers Commissioner Gordon and Salaam Remi.

On the day that Amy signed her publishing deal, a meeting was arranged with Guy Moot and everyone at EMI. Amy had already missed one meeting â probably because she'd overslept again â so they'd rescheduled. Nick Shymansky called Amy and told her that she must be at the meeting, but she was in a foul mood. He went to pick her up and was furious because, as usual, she wasn't ready, which meant they'd be late.

âI've had enough of this,' he told her, and they ended up having a screaming row.

Eventually he got her into the car and drove her into London's West End. He parked and they got out. They were walking down Charing Cross Road, towards EMI's offices, when Amy stopped and said, âI'm not going to the fucking meeting.'

Nick replied, âYou've already missed one and there's too much at stake to miss another.'

âI don't care about being in a room full of men in suits,' Amy snapped. The business side of things never interested her.

âI'm putting you in that dumpster until you say you're going to the meeting,' he told her.

Amy started to laugh because she thought Nick wouldn't do it, but he picked her up, put her in the dumpster and closed the lid. âI'm not letting you out until you say you're coming to the meeting.'

She was banging on the side of the dumpster and shouting her head off. But it was only after she'd agreed to go to the meeting that Nick let her out.

She immediately screamed, âKIDNAP! RAPE!'

They were still arguing as they walked into the meeting.

âSorry we're late,' Nick said.

Then Amy jumped in: âYeah, that's cos Nick just tried to rape me.'