Amy & Roger's Epic Detour (2 page)

Third Night:

Terre Haute, Indiana

Fourth Night:

Akron, Ohio

End:

Stanwich, Connecticut

I will then drive Roger to his father’s house in Philadelphia. Please drive safe!

Contents

But I think it only fair to warn you, all those songs about California lied.

You ain’t never caught a rabbit, and you ain’t no friend of mine.

I’d like to dream my troubles all away on a bed of California stars.

You’ll be missed, Miss California.

2 The Loneliest Road in America

Long-distance information, give me Memphis, Tennessee.

She’s gonna make a stop in Nevada.

We’re on the road to nowhere. Come on inside.

Yesterday, when you were young . . .

A love-struck Romeo sings a streetsuss serenade.

And you’re doing fine in Colorado.

Have you ever been down to Colorado? I spend a lot of time there in my mind.

Those memories so steeped in yesterday. Those memories you couldn’t run away.

4 Through Adversity to the Stars

I’ve reached the point of know return.

Where they love me, where they know me, where they show me, back in Missouri.

I called your line too many times.

I found my thrill on Blueberry Hill.

We will sing one song for the old Kentucky home.

You’d better go on home, Kentucky gambler.

I said, blue moon of Kentucky, keep on shining.

We both will be received in Graceland.

Well they’ve been so long on Lonely Street they ain’t ever going to look back.

I was on your porch last night.

I’ll be right here with you, come what may.

If you don’t mind, North Carolina is where I want to be.

Country roads, take me home to the place I belong.

You’ve Got a Friend in Pennsylvania.

Good-bye, so long, farewell . . .

Into the woods, then out of the woods, and home before dark.

—California state motto

I sat on the front steps of my house and watched the beige Subaru station wagon swing too quickly around the cul-de-sac. This was a rookie mistake, one made by countless FedEx guys. There were only three houses on Raven Crescent, and most people had reached the end before they’d realized it. Charlie’s stoner friends had never remembered and would always just swing around the circle again before pulling into our driveway. Rather than using this technique, the Subaru stopped, brake lights flashing red, then white as it backed around the circle and stopped in front of the house. Our driveway was short enough that I could read the car’s bumper stickers:

MY SON WAS RANDOLPH HALL’S STUDENT OF THE MONTH

and

MY KID AND MY $$$ GO TO COLORADO COLLEGE

. There were two people in the car talking, doing the awkward car-conversation thing where you still have seat belts on, so you can’t fully turn and face the other person.

Halfway up the now overgrown lawn was the sign that had been there for the last three months, the inanimate object I’d grown to hate with a depth of feeling that worried me sometimes. It was a Realtor’s sign, featuring a picture of a smiling, overly hairsprayed blond woman.

FOR SALE

, the sign read, and then in bigger letters underneath that,

WELCOME

HOME.

I had puzzled over the capitalization ever since the sign went up and still hadn’t come up with an explanation. All I could determine was that it must have been a nice thing to see if it was a house you were thinking about moving into. But not so nice if it was the house you were moving out from. I could practically hear Mr. Collins, who had taught my fifth-grade English class and was still the most intimidating teacher I’d ever had, yelling at me. “Amy Curry,” I could still hear him intoning, “

never

end a sentence with a preposition!” Irked that after six years he was still mentally correcting me, I told the Mr. Collins in my head to off fuck.

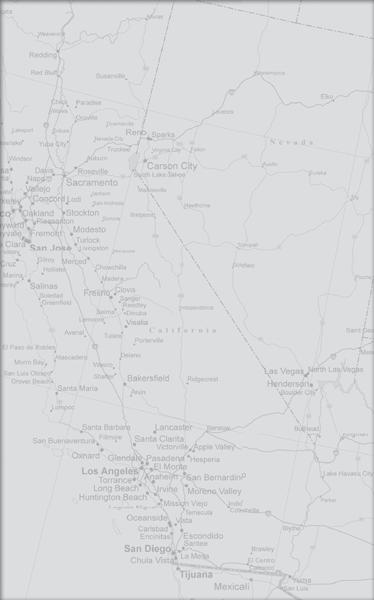

I had never thought I’d see a Realtor’s sign on our lawn. Until three months ago, my life had seemed boringly settled. We lived in Raven Rock, a suburb of Los Angeles, where my parents were both professors at College of the West, a small school that was a ten-minute drive from our house. It was close enough for an easy commute, but far enough away that you couldn’t hear the frat party noise on Saturday nights. My father taught history (The Civil War and Reconstruction), my mother English literature (Modernism).

My twin brother, Charlie—three minutes younger—had gotten a perfect verbal score on his PSAT and had just barely escaped a possession charge when he’d managed to convince the cop who’d busted him that the ounce of pot in his backpack was, in fact, a rare California herb blend known as Humboldt, and that he was actually an apprentice at the Pasadena Culinary Institute.

I had just started to get leads in the plays at our high school and had made out three times with Michael Young, college freshman, major undecided. Things weren’t perfect—my BFF, Julia Andersen, had moved to Florida in January—but in retrospect, I could see that they had actually been pretty wonderful. I just hadn’t realized it at the time. I’d always assumed things would stay pretty much the same.

I looked out at the strange Subaru and the strangers inside still talking and thought, not for the first time, what an idiot I’d been. And there was a piece of me—one that never seemed to appear until it was late and I was maybe finally about to get some sleep—that wondered if I’d somehow caused it all, by simply counting on the fact that things wouldn’t change. In addition, of course, to all the other ways I’d caused it.

My mother decided to put the house on the market almost immediately after the accident. Charlie and I hadn’t been consulted, just informed. Not that it would have done any good at that point to ask Charlie anyway. Since it happened, he had been almost constantly high. People at the funeral had murmured sympathetic things when they’d seen him, assuming that his bloodshot eyes were a result of crying. But apparently, these people had no olfactory senses, as anyone downwind of Charlie could smell the real reason. He’d had been partying on a semiregular basis since seventh grade, but had gotten more into it this past year. And after the accident happened, it got much,

much

worse, to the point where not-high Charlie became something of a mythic figure, dimly remembered, like the yeti.

The solution to our problems, my mother had decided, was to move. “A fresh start,” she’d told us one night at dinner. “A place without so many memories.” The Realtor’s sign had gone up the next day.

We were moving to Connecticut, a state I’d never been to and harbored no real desire to move to. Or, as Mr. Collins would no doubt prefer, a state to which I harbored no real desire to move. My grandmother lived there, but she had always come to visit us, since, well, we lived in Southern California and she lived in Connecticut. But my mother had been offered a position with Stanwich College’s English department. And nearby there was, apparently, a great local high school that she was sure we’d just love. The college had helped her find an available house for rent, and as soon as Charlie and I finished up our junior year, we would all move out there, while the

WELCOME

HOME Realtor sold our house here.

At least, that had been the plan. But a month after the sign had appeared on the lawn, even my mother hadn’t been able to keep pretending she didn’t see what was going on with Charlie. The next thing I knew, she’d pulled him out of school and installed him in a teen rehab facility in North Carolina. And then she’d gone straight on to Connecticut to teach some summer courses at the college and to “get things settled.” At least, that’s why she said she had to leave. But I had a pretty strong suspicion that she wanted to get away from me. After all, it seemed like she could barely stand to look at me. Not that I blamed her. I could barely stand to look at myself most days.

So I’d spent the last month alone in our house, except for Hildy the Realtor popping in with prospective house buyers, almost always when I was just out of the shower, and my aunt, who came down occasionally from Santa Barbara to make sure I was managing to feed myself and hadn’t started making meth in the backyard. The plan was simple: I’d finish up the school year, then head to Connecticut. It was just the car that caused the problem.

The people in the Subaru were still talking, but it looked like they’d taken off their seat belts and were facing each other. I looked at our two-car garage that now had only one car parked in it, the only one we still had. It was my mother’s car, a red Jeep Liberty. She needed the car in Connecticut, since it was getting complicated to keep borrowing my grandmother’s ancient Coupe deVille. Apparently, my grandmother was missing a lot of bridge games and didn’t care that my mother kept needing to go to Bed Bath & Beyond. My mother had told me her solution to the car problem a week ago, last Thursday night.

It had been the opening night of the spring musical,

Candide

, and for the first time after a show, there hadn’t been anyone waiting for me in the lobby. In the past, I’d always shrugged my parents and Charlie off quickly, accepting their bouquets of flowers and compliments, but already thinking about the cast party. I hadn’t realized, until I walked into the lobby with the rest of the cast, what it would be like not to have anyone there waiting for me, to tell me “Good show.” I’d taken a cab home almost immediately, not even sure where the cast party was going to be held. The rest of the cast—the people who’d been my closest friends only three months ago—were laughing and talking together as I packed up my show bag and waited outside the school for my cab. I’d told them repeatedly I wanted to be left alone, and clearly they had listened. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise. I’d found out that if you pushed people away hard enough, they tended to go.

I’d been standing in the kitchen, my Cunégonde makeup heavy on my skin, my false eyelashes beginning to irritate my eyes, and the “Best of All Possible Worlds” song running through my head, when the phone rang.

“Hi, hon,” my mother said with a yawn when I answered the phone. I looked at the clock and realized it was nearing one a.m. in Connecticut. “How are you?”

I thought about telling her the truth. But since I hadn’t done that in almost three months, and she hadn’t seemed to notice, there didn’t seem to be any point in starting now. “Fine,” I said, which was my go-to answer. I put some of last night’s dinner—Casa Bianca pizza—in the microwave and set it to reheat.