Amy & Roger's Epic Detour (25 page)

“Let me talk to Roger,” my mother said. “You’re clearly getting hysterical.”

“He’s sleeping,” I said sharply, a tone I’d almost never used with anyone, and certainly not my mother. “It’s six a.m. here. And I’m

not

getting hysterical.”

“You will come home right now—”

“I don’t think we will,” I said. The scary, huge anger was beginning to ebb and was being replaced by a kind of recklessness that I hadn’t felt in a long time, if ever. “I’ll be there soon, but there’s some stuff we want to see first.”

“You will not,” said my mother, and she was using the voice that usually ended any discussions. But now it just seemed to be egging me on. “You will come home immediately—”

“Oh, so you want me to turn around and go back to California? Because we can do that.”

“I meant,” she said, “come to Connecticut. You know that.” She now sounded mostly tired and sad, like someone had let all the anger out of her voice. Hearing this shift, I suddenly felt guilty, on top of angry and scared and sad myself.

“We’ll be there soon,” I said quietly. I was crying now, and barely even trying to hide it from her. What was so terrible was that this was my

mother

, and she was so close, just on the other end of the phone. All I wanted to do was to just open up to her, tell her how I was feeling, and have her tell me it would be all right. Instead of this. Instead of how hard this was. Instead of any of the conversations we’d had over the past few months. Instead of feeling so far away from her. Instead of feeling so alone. “Mom,” I said softly, hoping that maybe she’d feel the same way, and maybe we’d be able to talk about it.

“I am calling Marilyn and letting her know what her son has been up to,” she said, her voice now clipped and cold. Taking care of things. I knew the tone well. “If you want to do this, good luck. Just know that you are totally on your own. And when you do get here, know that there will be serious consequences.”

“Okay,” I said quietly, feeling worn out. “All right.”

“I am very,” my mother said, and I heard her voice shaking a little now. With anger, or suppressed emotion, I had no idea. “

Very

disappointed in you.” Then the phone went dead, and I realized my mother had just hung up on me.

I stared down at the phone and wondered if I should just call her back and tell her that I was sorry and we’d be there as soon as possible. I’d still get in trouble, but probably less trouble. I didn’t want to do that, but I also didn’t want to go the rest of the trip feeling guilty. I played with the room key, turning it over in my hands. And that’s when I saw the message printed in white on the purple card.

WANDERING IS ENCOURAGED

.

“Checking out?” the girl behind the front desk asked cheerfully. Roger and I nodded at her, both of us a little blearily. After I’d returned to the room, I’d gone back to bed but hadn’t slept much at all, just staring at the gradually lightening ceiling and replaying the conversation with my mother. I must have drifted off a little, though, because the wake-up call at nine—the one I’d forgotten I’d left the night before—had startled me from sleep. When I had started to get dressed in the bathroom after a quick shower, I’d remembered that I no longer had my own clothes. I’d stared down at my suitcase, with no idea how to put outfits together like Bronwyn could. I’d finally just grabbed whatever was on top—a long black tank top and gray pants that were like a combination of jeans and leggings.

But it seemed that Bronwyn’s clothes were magic, as I could see in the mirror behind the desk that I somehow managed to look more pulled-together than I had any right to. I yawned, feeling exhausted, and even though I covered my mouth, I saw Roger yawn as well about three seconds later.

“Okay …,” the girl said, typing on her computer. I wondered how many cups of coffee she’d had to be this awake, and this friendly, this early. Her name tag read

KIKI

…

HERE TO HELP

. “So no charges except the one night’s stay, is that correct?”

“Right,” I said, stifling another yawn.

“And was everything to your liking?”

“Fine,” I said, figuring I should take this one, since Roger hadn’t been conscious for almost any of the stay.

“All right,” said Kiki, fingers flying over her keyboard. “Excellent. So I’ll just put that on the card I was holding the room on?”

“Yep,” I said, mentally rolling my eyes at myself, but feeling resigned to the fact that I was, apparently, going to occasionally speak like a cowpoke from now on. Kiki nodded, smiled, and headed off to the small room behind the desk. I turned to Roger, leaning my elbows on the counter. “Breakfast?”

“If breakfast involves coffee,” he said, rubbing his eyes, “then yes.”

“I’m sorry, Miss Curry,” Kiki said when she returned, looking a lot less friendly than she had just a minute before. “I’m afraid your card has been declined.”

I blinked at her. “What?” I asked, flummoxed.

“I’ve tried it twice,” she said, sliding the card across the counter at me, touching it with only one finger. “It’s not good. Do you have another card?”

“Well,” I said, looking through my wallet, as though there would magically be another credit card in there. “Um …” I didn’t understand how this could be happening. The card wasn’t even attached to my bank account; it was linked to my mother’s credit card. As soon as I thought this, I knew what had happened. I felt my stomach drop as I realized what my mother had meant when she told me I was now on my own. “Oh God, Roger,” I said, turning to him. “There’s something I should probably tell you.”

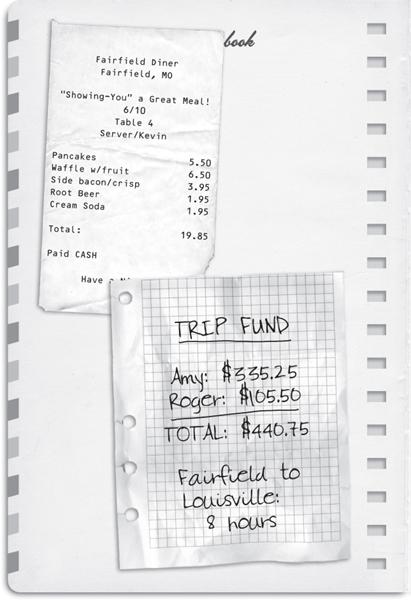

Roger pushed our shared side of bacon toward me, and I took a piece. It was extra crispy, extra greasy, and really good. But that wasn’t doing much to help the churning in my stomach. I wasn’t sure we were going to be able to pull this off.

I had the atlas next to me on the table, open to the map of the country. The thought of facing all that road between Missouri and Connecticut—without the safety net of an emergency credit card—was making me feel a little sick. We’d pooled our funds, which left us with $440 to get to the East Coast. I’d provided the lion’s share, thanks to my mother’s drawer egg. When Roger had raised his eyebrows at my cash, I’d mumbled something about my mother giving it to me in case places didn’t accept cards.

“What do you think?” I asked, looking down at the pile of money on the table between us. Our waiter, passing by, must have thought that we were assembling his tip, as he stopped and gave us both water refills, accompanied by a big smile.

Roger rubbed his hand over his forehead, which I now recognized was something he did when he was worried. “I think it might be enough,” he said. “Hopefully.” He pulled the plate of bacon back to him, took a piece, and crunched down on it. Then he looked out the window, which provided a beautiful view of the parking lot, for a long moment. “I guess I’m just surprised,” he finally said. “When your mother told you to come back, you said no.” He looked across the table at me and raised his eyebrows.

“I know,” I said. I still couldn’t believe that I’d done it—that we were now cut loose, and on our own in the middle of America. That my mother had basically washed her hands of me. I looked away from his direct gaze and down at the scratched surface of the table. Someone had etched into it

RYAN LOVES MEGAN ALWAYS

.

“Why?” Roger asked simply.

I glanced up at him. I hadn’t asked myself this yet. Saying no had just been my first response. “Because …” I looked out the window as well, beyond the parking lot to the interstate, where the cars were rushing by, heading home, running away, all of them off to somewhere else. I suddenly had the most overwhelming urge to get into the Liberty and join them. “Because we’re not done yet, right?”

Roger smiled but didn’t say anything, choosing instead to eat a piece of bacon pensively, something I wouldn’t have thought possible without seeing the proof.

“I mean,” I said, watching his face closely, “you haven’t seen Hadley yet.” When he still didn’t respond, I felt a sense of dread creep over me. I suddenly felt chilled in Bronwyn’s tank top, even though sunlight was hitting the table and I had been too warm a moment ago. What if he wanted to end it? I had just assumed Roger would want to keep going. But maybe he didn’t. Maybe we were going to change the route and head directly to Connecticut. The thought of being there, of having to begin my life there with my now furious mother, made me feel panicky. I wasn’t ready to do that yet. “But if you want to stop it,” I said, trying to keep my voice level, like saying this wasn’t completely terrifying, “we can.”

“No, it’s not that,” he said, looking across at me. He ran his hands through his hair, bringing it from its post-shower neatness to its normal messiness, and sighed. “I’m supposed to be the responsible one here. My mother is not going to be happy about this either. And I don’t want to get you into trouble.”

“You’re not,” I said quickly. “I did that on my own, believe me.”

“I just feel guilty about this.”

“Don’t,” I said. “Really.” I looked at him closely. “Do you want to stop?” I held my breath, hoping for the sake of my health that he wouldn’t take long to answer.

Roger looked across the table at me for a long moment, then shook his head. “I don’t,” he said, sounding a little surprised by the answer. I let out a long breath and felt my stomach unclench a little.

Our waiter passed by then, dropping our check and a handful of cellophane-wrapped mints on the table.

Roger took out his phone. “I should make some calls,” he said. “I still haven’t been able to talk to Hadley. And I should probably call my mother before yours does.”

“I’ll take care of this,” I said, counting out money for the check.

“You want to hold on to that?” Roger asked, nodding at the rest of the money. “I’d be worried I’d lose it.”

“Sure,” I said, folding the bills and tucking them in my wallet.

“Meet you at the car,” he said, grabbing one of the mints off the table and heading out the door, the bell above signaling his exit.

I looked down at the map and traced the route we’d take to Kentucky. We’d estimated about eight hours to get there, so we should be there by early evening, six or seven. I looked below Kentucky and saw Tennessee. And in the corner of the state, almost to Arkansas, was Memphis. I let my finger rest on the bolded name for a moment, thinking about the trip I was supposed to be on this summer—the trip that would have taken me there. To Memphis, but specifically to Graceland. It was strange to think how close we were going to be to it once we got to Louisville. Probably only a few hours away. But it would be backtracking. And I didn’t want to go without my father. Which meant, then, that I never would.

I closed the atlas, trying to push this unsettling thought away. I paid the bill, placing the money on the check and securing the waiter’s tip under my water glass. I figured I’d given Roger enough time to make his calls in private and got up to leave. As I did, my eyes caught the graffiti again. I wondered who Ryan and Megan were. And if, wherever they were, they’d made it. I wondered how anyone could have been so sure about a concept so tenuous and impossible as

always

that they’d be willing to carve it into a tabletop.

I glanced at it for a moment longer, then headed out of the diner, squinting against the sun.

I found my thrill on Blueberry Hill.

—Elvis Presley

S

EVEN YEARS EARLIER

My father swung the car around into a spot in front of the Raven Rock tennis complex and leaned back so that I could reach over and honk the horn. I used the honk we always used for Charlie,

honk-honk-honkhonkhonk

, what my father for some reason called “shave and a haircut.”

We sat back to wait, and a moment later,

From Nashville to Memphis

, the CD that had gotten us from home to 21 Choices and then to the tennis complex ended, and started over at track one. This was not permitted in my father’s car. In his mind, once you started listening to a CD on repeat, you stopped hearing its nuances. “Maestro?” he asked, turning to me.