Amy & Roger's Epic Detour (24 page)

“I know that,” I said carefully. “Haven’t I been talking to you?” I asked, deciding to deliberately misunderstand what he was saying. “Have we not been talking?”

He sighed and looked out at the road, and I knew he hadn’t bought it. Of course I knew what he meant. But it was one thing to tell Walcott, since I knew I wasn’t going to see him again. Opening up to Roger would be a wholly different thing. I’d have to sit with him in the car afterward, for miles and miles and hours and hours. And what if it was too much for him?

“I just …,” I said. I took a breath, so I wouldn’t break down before I even started. “It’s just hard for me. To talk about this. I mean.” Or to complete full sentences, apparently. Amy! wouldn’t have had this problem. Amy! would have had no issue with sharing her feelings and the things that scared her most with the person who was offering to hear them. But then again, Amy! probably had no issues. I really, really hated Amy!.

“I know it is,” Roger said quietly. The mix ended, and he didn’t start it up again. The iPod’s tiny screen glowed for a moment, then faded, and the only sound in the car was the rhythmic thwapping of the wipers across the windshield, which remained clear for only a second before the rain engulfed it again.

“It’s not that I don’t want to talk,” I said without thinking about it, and as soon as the words were out of my mouth I realized that they were true. I did want to talk. I’d wanted to talk for months. And here was someone who was offering to listen. So why did this seem so impossible? Like I was being asked to speak Portuguese, or something equally difficult? “I just …” I didn’t even seem to possess the words to finish that sentence. I hugged my knees into my chest and looked out the window.

“All right,” Roger said after a moment. “I’ll start, okay? Twenty Questions.”

“Oh,” I said, a little surprised that we were switching topics so quickly. Because to be honest, I’d almost felt ready to talk to him. “Okay. Is it a person?”

“No,” Roger said, smiling. “I mean, I’ll ask you questions. And that way it might be easier for you to talk. Maybe?”

I was both relieved and anxious that we were staying on me, that I would have to talk. “Twenty seems like a lot,” I said. “How about five?”

“Five Questions? Doesn’t exactly have the same ring to it.”

“And I get to ask you, too,” I added on impulse. “It’s only fair that way.”

Roger drummed his fingers on the steering wheel, then nodded. “Okay,” he said. “Ready?” I nodded. Mostly, I wanted to just get this over with. “Why don’t you want to drive?” he asked.

I swallowed and concentrated on the wipers going back and forth. And even though Roger could see me and I him, I was suddenly glad for the darkness in the car. It made it easier to pretend that he couldn’t see that I was trying hard not to cry, that my chin had apparently taken on a life of its own, and I no longer had any control over it. “There was an accident,” I said finally, forcing the words out.

“A car accident?”

“Yes,” I said. I was working very, very hard to keep control of myself, but I was on the verge of bursting into tears, and there was nowhere to go if that happened. No bathroom stall to hide in, nowhere to run.

“When was this?” Roger was asking me these questions gently, and quietly, but he might as well have been shouting them at me, that was how it felt to hear them, knowing I would have to answer.

“Three months ago,” I said, and felt my voice crack a little on the last word. “March eighth.”

“That’s all?” Roger asked, sounding surprised, and sad.

“Yes,” I said. I took a deep breath and tried to take a lighter tone. “That counts as one of your questions, you know.” From the way my voice was shaking, and the way it sounded thick to me, I had a feeling that my lighter tone had not been successful.

“Last one,” he said. He glanced at me again and asked, more quietly than ever, “Do you want to tell me what happened?”

I’d known this was coming, but that didn’t make it any easier to hear him ask. Because there was a piece of me that wanted to talk about it. Deep down, somewhere, I knew that it would be better in the long run, to face it. That the bone would have to be set in order to heal properly, not weak and crooked. I had seen a flash of the Old me in Bronwyn’s mirror in Colorado. I wanted to see her again. I wanted to try to get back to who I had once been. And the rational piece of me knew that not talking about it was keeping me from sleeping and was probably making my hair fall out.

But there was another piece of me, the part I’d been listening to for the past three months, that told me to turn away, not answer, pull the covers over my head and keep on hiding.

Because Roger didn’t know what had happened. If he had, he wouldn’t be looking at me the way he had been. Once he found out, he’d turn away from me, then leave me altogether, just like Mom and Charlie had done. And I didn’t want to have to face the look in his eyes when I stopped being whatever he thought I was and turned into something else. I unclasped my knees, placed my feet on the floor, and looked at him. “No,” I said quietly. But my voice seemed to reverberate in the silent car nonetheless.

Roger looked over at me, then back at the road, pressing his lips together, nodding. Then he brought the iPod to life again and turned up the music, beginning his mix again.

I felt like I’d let him down, but I knew that it was better, in the end, to keep this inside. I’d gotten good at that. And soon he’d stop asking. Soon this would just be who I was. Soon Old me would be dead too. I tipped my head against the cold glass of the window. When I felt myself begin to cry, I didn’t fight against it. And when I caught my reflection in the dark window, I wasn’t able to tell what was tears and what was rain.

I called your line too many times.

—Plushgun

M

ARCH

8—

THREE MONTHS EARLIER

I headed back inside the house, pocketing my cell phone. My mother wasn’t in the kitchen, but I could hear her in the family room, talking on the phone, her words clipped and anxious.

“Charlie,”

I muttered, hating that my brother was doing this to us.

I took the stairs two at a time up to his room and opened the door, and the strong scent of Glade Plug-Ins hit me. I always thought it might have raised my parents’ suspicions that Charlie’s room consistently smelled like potpourri, but they had never seemed to think anything of it. Or if they had, it was like they didn’t want to deal with it, so they never said anything.

Charlie hadn’t appeared in his room, and it looked just like it always did. His posters of James Blake and Maria Sharapova were tacked to the walls, and the bed, never made, was rumpled as usual. Charlie told me that he’d discovered if you never made your bed, it was harder for people to tell if you’d slept in it the night before. I closed the door and checked my phone again. Charlie was usually good at covering his tracks; it was how he’d been able to get away with things for so long.

I thought back to the conversation I’d had with him on our porch six months ago, my failed attempt at an intervention. When I’d threatened to tell Mom and Dad, I’d also threatened to stop covering for him. But I hadn’t done either, just like he’d said I wouldn’t, and here I was ready to try to fix the situation, if only he would give me some information. I sent him a text—

WHERE ARE YOU

???—and waited, staring down at my phone. But I didn’t get a reply.

I headed back downstairs and heard my parents’ voices in the kitchen. I sat on the bottom step, partially hidden but able to hear what was being said.

“Who else should we call?” my mother asked, and I could hear the raw worry in her voice. I couldn’t help thinking that if it had been me who had disappeared, she wouldn’t be worried. She’d be furious. But then, Charlie always had been her favorite.

“Maybe we should just hold tight,” said my father. “I mean, he’s sure to turn up….”

The kitchen phone rang, and I stood up and stepped into the kitchen, leaning back against the counter. My father smiled at me when he saw me, but I could see how stressed he was. The whistling figure pushing the lawn mower was gone.

“Hello,” my mother said, grabbing the kitchen phone. Her expression changed as she listened to what was being said on the other end. Genuine fear was now mixed in with the worry. “I don’t understand,” she said. “He’s

where

?”

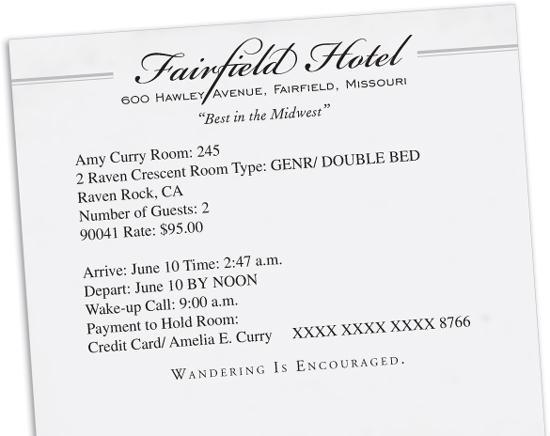

I hadn’t been able to sleep. We’d checked into a hotel when it became clear that Roger was hitting his wall. He’d gone right to sleep, but I’d spent three hours lying awake, looking at the space between Roger’s bed and my own, watching the clock. Roger was sleeping peacefully, and as I saw his back rise and fall, I envied him that sense of peace. I had taken my cell phone out and placed it next to me on the bed, and every time I opened it, I saw my voice mail icon illuminated. My sense of dread was growing. I knew I’d have to call my mother soon—in theory, we were supposed to be heading in from Ohio and getting to Connecticut that afternoon. We were not supposed to be in Missouri and heading for Kentucky. We were not supposed to be in a different time zone. When six a.m. rolled around, I gave up on the idea of sleep entirely. I grabbed the purple plastic room key card and my phone and headed out to the hallway, closing the door slowly behind me so it wouldn’t slam and wake Roger.

I walked to the end of the hallway, where a large window overlooked the highway. Then I took a deep breath and pressed the speed dial for my mother’s cell phone.

She answered on the second ring, sounding much more awake than I would have imagined she’d be at seven in the morning, her time. “Amy?” she asked. “Is that you?”

“Hi, Mom,” I said.

“Hi, honey,” she said. I felt myself blinking back tears, just hearing her voice. I knew that this was why I had avoided talking to her for as long as possible. Because I was feeling so many things right now, I wasn’t even sure how to process them all. It was like I was in overload. It felt so good to hear her voice, but a second later I was furious, and I wasn’t even sure exactly why.

“I’m so glad you called. I have to say, Amy,” she said, and the sharpness was coming back into her tone, what Charlie called her “professor voice,” even though she had hardly ever used it on him, “I’ve been very disappointed with how out of touch you’ve been during this whole process. I feel like I’ve barely heard from you, I hardly ever know where you are—”

“We’re in Missouri,” I interrupted her, which was something I almost never did, since I always knew her next words would be,

Don’t interrupt me, Amy.

“Don’t interrupt me, Amy,” my mother said. “It’s just incredibly irresponsible, and—did you say Missouri?”

“Yes,” I said. I felt my heart hammering again, the same feeling that I always used to get whenever I knew I was going to get in trouble.

“What,” said my mother, her voice low and steady, always a bad sign, “on

earth

are you doing in Missouri?”

“Just listen for a second, okay?” I asked, swallowing and trying to get my bearings.

“Am I stopping you?”

“No. Okay.” I held the phone away from my ear for a moment and looked out on the highway. I thought I could see a little tiny ribbon of light creeping up on the horizon, bringing the dawn. But it might have just been brake lights. “So Roger and I,” I said, trying not to think about how mad my mother was probably growing on the other end of the phone, “we decided to take a little bit of a scenic route. We’re fine, I promise, he’s driving safely and we’re stopping whenever he gets tired.” There was silence on the other end of the phone. “Mom?” I asked tentatively.

“Did you just say,” she asked, sounding more incredulous than angry, “that you’re taking the

scenic route

?”

“Yes,” I said, swallowing. “But I promise we’ll be there before too long. We’re just—”

“What you will do,” she said, the anger now back in her voice, full force, “is get in the car and drive straight to Connecticut. I will put Roger on a train to Philadelphia, and then you and I will discuss your consequences.”

“Don’t interrupt me, Mom,” I said. The words were out of my mouth before I even registered what I was saying. I held the phone away from my face as I stifled a shocked laugh.

“Amelia Curry,” she said, saying the two words that inevitably meant a serious consequence was coming after them. “You are on very thin ice, young lady. This is not some sort of … pleasure cruise. This is not a vacation. You had one simple task to do. As though we haven’t been through enough, you decide to …” her voice shook, and trailed off for a moment, but a second later she was back, sounding as in control as ever. “Why are you doing this?” she asked. “You’re making my life much harder—”

“I’m making your life harder?” I repeated, feeling like I’d lost all sense of perspective, just feeling an overwhelming anger that seemed like it might take me over. “I’m making

your

life harder?” I could hear my voice coming out, loud and a little uncontrolled, sounding nothing like my normal voice. Tears had sprung to my eyes, and my hand that was holding the phone was shaking. I was furious, and the depth of it was scaring me. “Seriously?” I asked, feeling my voice crack and two tears slide down my cheek.