An Introduction to Rowing (7 page)

Read An Introduction to Rowing Online

Authors: HL Fourie

The coxswain should steer by aiming at a distant point and making small adjustments towards that point. It is better to under steer towards the aiming point rather than to over steer and have the boat fishtail towards the target.

Steering may be done during the recovery or during the drive, and to achieve the desired amount of turn the rudder movement may need to be applied over several strokes. Steering during the recovery is most responsive because the boat is fastest at this time. However, since the blades are out of the water during the recovery the boat is at its most unstable state and big movements of the rudder will affect the balance of the boat. The smaller rudder movement will result in less drag and so this method is usually preferred during a race.

Steering during the drive is less responsive but has the advantage that the boat is more stable. The disadvantage of this method is that the rudder movement will need to be applied over more strokes to achieve the same turning effect resulting in more drag.

When the shell is in motion, steering can also be done by added or reduced pressure on the starboard or port oars. This may also be used when sharper turns need to be negotiated. For example, the coxswain would call "port pressure" to start a turn to starboard and then "even pressure" to stop the added pressure.

The shell can also be turned using squared oars on the starboard or port side. This will check the boat on the side that the oars are squared causing it to turn in that direction. For example, the coxswain will call "Stroke hold water" to get the stroke to square his oar to make a turn to port.

Since the rule of passing is to navigate around a body of water by keeping the bank close to the starboard side of the boat, boats will typically need to make turns to port. To do this the coxswain will call "Port back" and "Starboard row".

When the shell is stationary, it can also be turned by taking backing strokes or rowing in the reverse direction. This is typically used when maneuvering the boat when docking or when lining the boat up at the start of a sprint race.

When the shell is stationary, it can be turned to starboard by getting seat 2 to take a one or more strokes. To turn more sharply, seats 2 and 4 can take strokes. This will also cause the shell to move forward. To rotate the shell in place in a clockwise direction, seat 2 should take some strokes while seat 7 does backing strokes.

The shell can be turned to port by getting bow seat to take a one or more strokes. To turn more sharply, bow seat and seat 3 can take strokes. To rotate the shell in place in a counter clockwise direction, the bow seat should take some strokes while the stroke seat does backing strokes.

The coxswain may decide to use both the rudder and added or reduced oar pressure in certain situations.

In a sweep boat the rowers have theirs oars extending to the starboard or port side of the shell. Novice rowers should try rowing both starboard and port positions to determine their preference and aptitude.

The hand closest to the rigger is called the inside hand and the hand furthest from the rigger is the outside hand. When rowing at port the left hand is the outside hand, and when rowing at starboard the right hand is the outside hand.

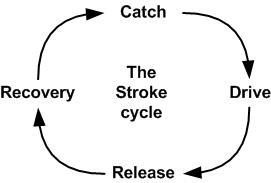

Rowing is a cycle of repeated strokes. Each stroke consists of four steps during which the seat slides between two positions: closest to the stern and closest to the bow.

1. The Catch is the instant at which the oar blade is placed in the water and the drive starts. The seat is at a position closest to the stern.

2. The Drive is when the oar blade is in the water and the rower is pulling on the oar. The rower drives the seat towards the bow by extending the legs.

3. The Release (also called the Extraction or the Finish) is the instant at the end of the drive when the oar blade is removed from the water. The seat is at a position closest to the bow.

Figure 40:

The Stroke Cycle

It is important to note that although the phases of the stroke have been identified and described here, when actually rowing the stroke must be a smooth, continuous movement from one phase of the stroke to the next and from one stroke to the next.

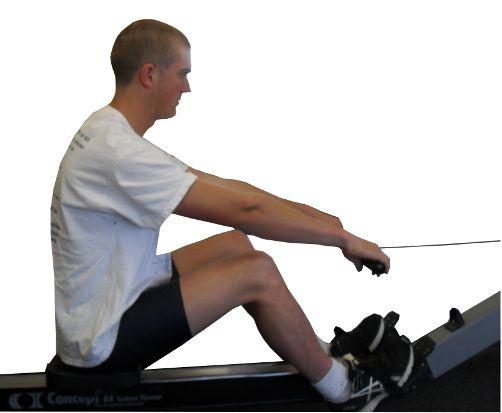

The rower starts the drive at the catch position with seat at the stern-most position with the knees bent and legs compressed with the arms extended towards the stern. The shins of the leg should be vertical, the chest resting on thighs, arms straight and the rower's weight on the balls of the toes. The rower's head should be up and be looking beyond the stern of the boat. Avoid looking down into the shell as this will cause the chin to drop and the back to be rounded. The rower's back should be erect and slightly pivoted forward. The outside shoulder should be slightly rotated towards the rigger and should be slightly higher than the inside shoulder. The outside arm will be between the rower's knees so they should be a natural distance apart. The body position is shown below.

Figure 41:

Body Position at the Catch

At the catch the rower places the oar blade into the water by rapidly raising the arms by pivoting them up straight-armed from the shoulders, and then starts to extend the legs to push the seat towards the bow of the boat. This applies pressure on the oar blade to drive the boat forward through the water. The drive may be broken into three sequential phases:

First, the rower extends the legs to push the seat towards the bow. This is called the leg drive. Most of the power for the stroke comes from this strong leg extension. There is no pivot of the back or bending the arms. The rower's back angle should be unchanged for the first half of the drive. The shoulder muscles should not be engaged, the arms should be extended forward as if hanging from the oar.

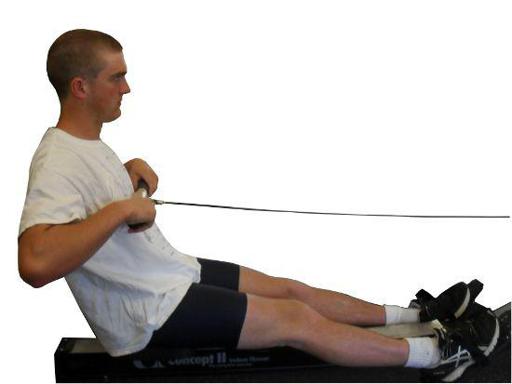

Next, the rower leverages the torso backwards towards the bow as the legs near full extension. The pivot of the torso toward the bow should occur during the last quarter of the leg drive. The body position as the rower starts to lean backwards is shown below.

Figure 42:

Body Position at the Half Slide

Finally, the rower draws the arms towards the chest when the torso has passed vertical. The hands should almost touch the chest just above the diaphragm and have enough room to drop to remove the blades from the water for the release. The body position at the Release is shown below.

Figure 43:

Body Position at the Release

This sequence is important because the muscle groups of the body used in the stroke: the legs, the back and the arms, have decreasing strength. The most powerful muscle group, the legs are used first, followed by a transition to the pivot of the back towards the bow, and finally the arms. The handle and seat should move together during the drive.

The rower starts the recovery by pushing down on the oar handle to lift the blade from the water at the release. The oar blade should come out of the water perpendicular to the surface of the water. Once the blade is out of the water the rower starts to feather the oar so that the blade of the oar is parallel to the surface of the water. The recovery may also be broken into three sequential phases:

First, the rower extends the arms out in front. This is the arms-away position shown in the picture below.

Figure 44:

Arms-away Body Position

Next, the rower leans the torso forward. The boat reaches its maximum velocity through the water.

Finally, when the torso is just past vertical, the rower starts to bend the knees which causes the seat to move towards the stern of the boat. The oar handle must be past the knees before they break. This bending of the knees occurs slightly more slowly than the drive and allows the rower a moment to recover. The boat now merely glides through the water.

The recovery completes with the seat moving toward the stern position and the legs compressing until the shins are vertical again. The shins should be vertical and aligned with the feet and not flared outward. It is important to achieve maximum leg compression in each stroke since the bulk of the power for the stroke comes from leg extension during the next drive.

The recovery phase of the stroke is performed more slowly than the drive, in fact only about a third of the time for the whole stroke cycle is used for the drive and two thirds is used for the recovery. This gives the rower a chance to rest and prepare for the next drive. The rowing ratio is the ratio of the time spent on the drive versus the time for the recovery. The value of the ratio should about 0.5, meaning that about twice time is spent during the recovery compared with the drive. The goal is to have a powerful drive followed by a relaxed recovery without rushing forward up the slide.

In summary the stroke is a repeated cycle as follows: catch, legs, back, arms, release, arms, back, legs. The stroke should represent power under graceful control with the minimum of splashing as the oar blade enters and leaves the water.

Feathering is done during the recovery phase of the stroke when the oar blade is out of the water. When feathered the blade of the oar is parallel to the surface of the water (with the face of the blade facing upwards) so that it meets less wind resistance and is able to slice through the air during the recovery. During the drive the wrists should be straight with the arms.