An Owl Too Many (13 page)

Authors: Charlotte MacLeod

Peter’s reply was blurred by a yawn too big to choke back. Helen handed him the disreputable tweed hat and mackinaw he’d dropped on a chair when they’d arrived.

“Come along, darling, you’re out on your feet. Winifred, you must be ready to drop. Would you like to drive back and spend the night with us again? You, too, Knapweed, if you don’t mind sleeping on the living-room sofa.”

“Thanks, Mrs. Shandy. I could sleep on a hat rack if I had to, but I think I ought to stay here and man the barricades in case there’s any trouble. Besides, we have people coming tomorrow.”

“Nobly spoken, Knapweed,” said Winifred. “You’re a dear to offer, Helen, but we’ll do quite all right in our own downy beds. We did expect a troop of Boy Scouts from Lumpkin Upper Mills to be bivouacked out here tonight doing their own owl count, but the scoutmaster called to say it was too cold. Translated, I expect that means their parents are afraid to let them come because of what happened to Mr. Emmerick.”

“And who could blame them?”

“Not I, surely. However, we do expect them first thing in the morning. I’m supposed to show them how to leach the bitterness out of acorns, then roast them over an open fire. They were supposed to gather their own acorns, but Knapweed and I collected a bucketful this afternoon to speed things up. With no untoward incident, I’m relieved to say. We’ve got them shelled and leaching in the brook.”

“Viola phoned a while back to tell us she’s feeling better and could come in for a while tomorrow if we needed her,” Knapweed put in, “but I said we could manage, so she’s going to wash her hair instead.”

“So you see we’re more or less back to normal,” said Winifred. “I’d offer you a cup of chamomile tea for the road, but you don’t look to me as if you need any. Good luck with the code, or whatever it is, and thank you for thinking of us. Nighty-night, Jane dear. Come again soon.”

Peter said, “Good night, Winifred,” just to keep in practice. Jane gave Knapweed’s hand a parting lick, which pleased him greatly. Helen fished out the car keys and got them back on the road, Peter and Jane both had to be waked up when they pulled into Charley Ross’s parking lot. Jane showed an inclination to walk the short way home. Helen protested.

“No, you don’t, young woman. You’re not going to start roaming the streets downtown like your cousin Edmund.”

Edmund was in fact only a sixth cousin once removed, but relatives were relatives in Balaclava County. Peter ended the matter by scooping up the cat and letting her work out her irritation on his mackinaw, which was long past hurting anyway.

“Now, we’re all going to have a nice, quiet Sunday,” Helen decreed as they walked up the hill. “We’ll sleep as late as we like and I’ll make us a nice big breakfast whenever we feel like eating.”

“Too bad we didn’t think to bum some acorns off Winifred,” said Peter. “We could sit around the backyard roasting them over a campfire.”

“Yes, dear.” Helen glanced up at the moonless, starless firmament. “I have a hunch those Boy Scouts aren’t going to get many acorns roasted tomorrow, unless they do it over the station fireplace. I don’t care what the weatherman said, I predict we’re in for a real rainstorm.”

As so often happened, Helen was right. Sunday morning never quite arrived. The sky stayed leaden; the rain lashed against the windows, drummed on the roof, and no doubt leaked around the bulkhead into the cellar. None of the Shandys got up to look; they were content to laze and drowse until Jane decided it was tummy time and Helen’s conscience got the better of her. Peter was the last one down. He found his wife at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee in front of her, sausages in the frying pan, a pitcherful of pancake batter ready for action, and Knapweed’s copies spread all over the place.

“Any luck, Mrs. Holmes?”

“Not a glimmer.” Helen gathered up the sheets and parked them on the cutting board with a can of cat food to hold them down. “I’ve phoned Winifred. The Boy Scouts aren’t coming, so she and Knapweed are going to wallpaper her living room. She’d been putting it off for a rainy day, and she’s not likely to find one rainier than this. She’s been out to check the rain gauges, there’s already upward of half an inch. They haven’t had any luck with Emmerick’s code. I had to tell them we haven’t, either. Maybe I’ll feel smarter after I’ve had something to eat.”

“Yes, pet. Want me to do the flapjacks?”

“Not if you’re planning to flip them in the air and try to catch them in the pan. You know what happened last time.”

“There’s gratitude, forsooth! Which of us had been nattering for three years about getting the ceiling done? And who provided the ultimate impetus?”

“I grant you the impetus, but what about the stove? I don’t know when I’ve seen Mrs. Lomax more upset. And that was after we’d scraped most of the batter off the burners. Go see if the Sunday paper’s come, since you burn to be helpful. I hope that child didn’t simply dump it on the doorstep and gallop off, the way he usually does.”

“If he did, what we have now is papier-mâché,” said Peter in a voice of doom. “Gad, what a downpour! Jane, get your nose out of that frying pan and come help Papa brave the elements.”

Jane made it clear that she felt her first duty was to the sausages, so Peter went alone. He managed better than he’d expected; the Boston paper was so wrapped around with circulars and classified ads, thanks to somebody’s having got it assembled the wrong way around, that the relatively meager news and editorial sections were damp only halfway through. Today, moreover, he found another quite unexpected, far less ponderous journal propped up against the front door, enclosed in plastic and dry as a bone.

The latter’s front page featured an exclusive, on-the-spot photo of a cadaver being toted down a woodland path by two well-groomed stalwarts in state-police uniform. There was another showing Chief Ottermole, looking even handsomer and groomier, thanks to Edna Mae’s fond attentions, arresting a medium-sized man who had his head turned away from the camera. Peter dumped the bigger and wetter paper in the umbrella stand and carried the other back to the kitchen.

“Look at this, Helen, the

Fane and Pennons

finally got around to putting out a special Sunday edition. Another milestone in history! Ottermole’s made the front page.”

“As when does he not? My stars and garters, Edna Mae’s going to run out of wall space. Isn’t there a picture of you anywhere?”

“Gad, I should hope not. Swope knows better.”

“Well, I think it’s discriminatory. We have walls too, you know.”

“Then why don’t you hang up that photograph of me at the county fair, judging the twenty-seven-pound Balaclava Buster that old coot from Outer Clavaton dragged in.”

“Yes, with your back to the camera and a rip in the seat of your pants.”

“Merely a snag. I happened to sit on a splintered rail at the cattle pens that some bored beast had been chewing on. You must admit the rutabaga came out well, though.”

“I grant you the rutabaga. Give those sausages a turn, will you? Gently, without histrionics.” Helen added two pancakes to the stack she was keeping warm in the oven and poured more batter. “I may as well finish the batch, we can have tea and crumpets this afternoon.”

Helen and Peter had been amused while in Britain to learn that crumpets resembled American batter cakes closely enough to make no great difference; this would be a good day for a high tea by the fireplace. They ate their excellent breakfast, read each other snatches of Cronkite Swope’s lively reportage, turned down the telephone so they wouldn’t hear it ring after they’d got one too many calls from neighbors who’d also been reading the

Fane and Pennon,

and tried not to think about various tasks they too had been putting off for a rainy day.

Every so often, one or both of them would take another whack at the code. The encyclopedia up at the college library would have given them the relative frequency of the various letters of the alphabet; but that would have meant a slog through the rain and this really was too beastly a day to bother.

About two o’clock in the afternoon, Timothy Ames slished across the Crescent with his cribbage board under his raincoat. His house was directly across from the Shandys’, which was about as far as anybody cared to go. Tim and Peter played. Helen retired to the kitchen to make fudge, not that they needed the extra calories but just because it was that sort of day. Once the nutmeats were in and the fudge set to harden, she picked up Knapweed’s copies again.

*

Vane Pursuit

, 1989.

P

ETER WAS IN THE

act of pegging out when he heard the cry from the kitchen.

“Dolt! Dizzard! Double-dyed dunderhead! How could I have been so blind?”

“Excuse me, Tim. I’d better see what’s up.” He dashed to the kitchen. “Wherefore the wailing, woman?”

“It’s toothpick letters, that’s all. Didn’t you play with them as a kid?”

“When I was a kid, one whittled one’s own toothpick out of a burnt match.”

“And carried it around in a little gold case, I suppose? Here, let me show you.”

“While Tim stacks the deck? I’ll get him in here. Wait a minute.”

He went back to the living room, but returned alone in a couple of minutes. “Tim says never mind, he’ll read the paper instead. The rain got into his hearing aid on the way over and he has a static problem. So what’s with the toothpicks?”

Helen had brought a box of toothpicks from the tiny pantry and was arranging them in geometric patterns on the table. “See, I’ve duplicated a set of symbols from Emmerick’s notebook.”

“Or Fanshaw’s.”

“Whichever. You’ll grant that I’ve got them right?”

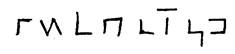

Peter nodded. What Helen had achieved was

“Featly formed, my love. Now what?”

“Now we add a few more toothpicks. Here, I think. And here, and—darn, I wish they wouldn’t skitter around like that. Here, and I think we just move this one down a little, and here, and what do we get?”

“Good question. Oh, I see now. I’ll be switched!

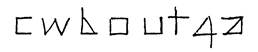

“CWBOUTGA. What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Well, ‘bout’ refers to boxing. Maybe CW is supposed to fight somebody in Georgia. Perhaps if we go through the rest of the notes—”

“Wait a second, could this be the key?”

As a boy, Peter had always enjoyed working out the rebuses in the family almanac. He shuffled through the notes and found the drawing from the back of the notebook. “Suppose, for the sake of argument, C stands for Compote and GA for Golden Apples?”

“Of course, darling! Then could WB stand for Winifred Binks? You say she practically owns that company.”

“According to her lawyers, she has controlling interest. So Compote Winifred Binks out Golden Apples. Or maybe the W means something else; it could stand for worried, or warning.”

“Or wanting or wishing or simply waiting. Waiting, perhaps, to see what Winifred’s going to do about her shares.”

“Or worried about what she might do. Or wanting to buy her out so she can’t do anything.”

“Sopwith, the trust officer, claims the Compotes can’t buy her out. They don’t have the money.”

“How does he know?”

“He damned well ought to, it’s his job to know. Well, this looks promising, unless we’re deluding ourselves. Let’s, as you suggest, press on. We don’t have to keep on with the toothpicks, do we?”

“Oh no, it’s just a matter of adding one more straight line to each of the symbols, you see. There’s a pencil beside the telephone, unless Jane’s been playing with it again.”

“That’s all right, I have one. What’s next?”

Working directly on the copies, Helen made light strokes. VBOKKCRED. “Could that mean Viola Buddley’s all right but Knapweed Calthrop is a Communist?”

“Could mean he’s red with embarrassment if Calthrop’s version of what happened out by the bird feeder is the true one,” said Peter. “Unless it’s some key word like red for stop or red for danger? Drat it, Helen, this is getting too thought-provoking for comfort. Why couldn’t the bastard have been more explicit?”

“Since he wrote them in code, he obviously didn’t want them to be easily understood,” Helen pointed out quite reasonably. “They could be just Emmerick’s reminders to himself of things he ought to tell Fanshaw when they got together. Or he could have left the notebook in the car for Fanshaw to find when he picked it up last night. And Fanshaw didn’t find it, which might explain why he showed up looking for Emmerick this morning. I do think it must have been Emmerick who made the notes, don’t you? He was the only one in a position to make judgments about Knapweed and Viola. Fanshaw had never been near the station before, had he?”