Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (4 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if she forever flies within that gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in her lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than the other birds upon the plain, even though they soar

.H

ERMAN

M

ELVILLE,

Moby-Dick

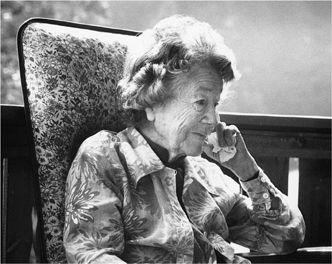

Anne Morrow Lindbergh on the balcony of her chalet

in Vevey, Switzerland, August 1988. (Photographed by the Author)

T

he first time I saw Anne Lindbergh was in Minnesota, in 1985, at an annual meeting of the Lindbergh Fund, the environmental organization established in honor of her late husband, Charles. In spite of the urgings of family and friends, Mrs. Lindbergh refused to meet me. For four days, I watched from afar as she bristled at the obsequity of admirers, as she exploded with warmth among friends, as she accepted awards and gave them graciously; I wished I could meet her face to face, if only for a moment.

But a tight circle of friends protected her with a fervor attendant on a holy shrine. Her presence lingered like incense behind closed doors. If, by chance, one approached the “forbidden,” angry voices rose in protest, forming a protective circle around her. Some who shielded her seemed proud to be part of this inner circle. Others appeared angered, even imprisoned by it. All seemed creatures of habit rather than of conviction, trapped in a script rehearsed for half a century.

They protected her, they said, because she was “weak;” weak with the scars of age and tragedy. And yet there was a paradox that begged to be understood. Those who treated her as though she were weak knew she was strong.

“Strong as steel,” they whispered to me in corners of the room while they tended their priestess as if she were a lost lonely child.

Fascinated by her mask, and by the intricate mythology she had created in its service, I wondered why this disciplined writer, this pioneering aviator, this fervent conservationist, this mother of five, and the wife of the indomitable Charles Lindbergh chose to appear weak? What was she concealing behind this elaborate charade?

With a notebook full of observations and a bitterness common among those who pursue the Lindberghs, I sat at the departure gate, waiting for the plane home to New York, when Mrs. Lindbergh, quite by chance, sat down beside me. Not believing the good fortune the gods had granted me, I reveled at being, for the first time, in the physical presence of a subject I had been studying for twenty years.

I sat very still, taking note of her deeply lined cheek, her angular profile, and her frail curved body, as she sat, Sphinx-like, in thought. How

small and insignificant she seemed, sitting in that blue vinyl chair, her head turned away from the bustling traffic of people, toward the glass-walled balcony overlooking the airfield. She sat cross-legged, drawing energy inward, not so much a presence as a receptacle for the sights and sounds that are the kaleidoscope of airport life. More striking than her posture or her stature was the fact that she was alone. No one recognized or followed her. No imposing husband sat beside her. None of her five children was there to disturb her thoughts or to demand her attention. She was a gentle sylph of a woman, girlish even in her old age, slightly bent and dressed in blue, watching the comings and goings of airport life behind dark, passably fashionable glasses. At any moment, I expected her to turn and greet me. I, after all, knew her well.

At the age of twenty-one, I had given birth to my daughter. We spent the summer at an island beach, and I read Anne Lindbergh’s book

Gift from the Sea

. It spread clear across my life like a finely focused lens. It was the mid-sixties, in the heat of an escalating war, when presidents and statesmen, visionaries and children were beaten and killed in the fevered anarchy of the streets. To those raised in the quiescence of the fifties, the line between law and lawlessness was nothing more than a matter of opinion.

Looking at history through our newspapers, we ordinary housewives, neither soldiers nor protesters, had no voice and had no answers. We had only questions—gnawing questions that consumed our neatly fashioned lives, turning every certainty into a battleground of ideas. My friends and I, finely dressed young matrons behind our proper English prams, walked our babies along city streets, stalking ideas as if we were jungle cats. What did it mean to be a woman? How did one live out one’s needs without violating oneself or those one loved? How could a woman be free and independent, yet part of a constellation of social expectations and relationships that threatened to eclipse her?

I

n little more than a hundred pages, in language so simple and lyrical that it was more poetry than prose, Anne Morrow Lindbergh set forth the answers in

Gift from the Sea

. Look inside yourself, she said. Strip life

of its conventions; reach down to the essentials. Find the core of your being. Make it an

oasis

for yourself and others. Take strength from it and create a space, sacred and inviolable, in which to become and express yourself. Do it gently, do it gracefully, without anger or destruction. Do it because the quality of your life—in fact, the quality of Western civilization!—depends on your authenticity.

I had read her book without knowledge of her past, her husband, or her fame. And yet understanding the genesis of her philosophy became an increasing obsession. How and where did she find these answers? How dare she answer with certainty the questions that threatened the fabric of our lives? I unearthed her books in libraries and bookstands. I read her diaries and letters as they appeared off the press.

Through her writing, Anne Lindbergh became my mentor and my friend. I walked alongside her, like some metaphysical voyeur, dusting myself off when she fell and applauding myself for her every victory. Her thoughts and her anguish became a laboratory for me to study my role as wife and mother, as well as to cultivate my literary ambition. I came to believe that if I were to understand Anne Lindbergh and the choices she had made, I could chart the process of female creativity, finding feminine consciousness in crises, heightened by the anguish and isolation of fame. I would know not only myself, but something more: the anatomy of a woman who had chosen to become a writer.

Now, after twenty years, and merely by chance, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, total stranger and intimate friend, was sitting beside me. I introduced myself and reached for her hand. Her touch was like a fluttering bird; energy and movement without flesh or place. She raised her eyebrow like a camera clicking its shutter. My image recorded, she withdrew. Out of indifference, she turned away.

Fueled by that chance meeting in 1985, I pursued her, making circles of words and relationships around her, forcing her to acknowledge my intent to write her story. Slowly, I pierced the inner circle.

T

wo years later, out of weariness as much as curiosity, Anne Morrow Lindbergh invited me to her mountain chalet in a small town east of Geneva, Switzerland.

The invitation held the fire of Old Testament sin. It was an act of intimidation hidden between the folds of social grace and literary allusion.

“I feel an aversion to having my

LIFE

written,” she wrote. “The aversion has to do with the appalling amount of publicity we have already had and my intense desire to escape from it … The aversion is not to you but to publicity, public scrutiny and the falsity of public images. In fact,

all

images. A man called Stiller once wrote about images in a novel. One of the characters says to another ‘You have made me an image … Every image is a “sin.”’”

In this country steeped in Calvinism, the language of the Ten Commandments had a forbidding ring: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image … for I the Lord am a jealous God.”

My mind both rejected and obeyed her warning. I too had Old Testament beginnings. Eastern European Orthodox Jews observed the ancient prescript, much like the Midwestern or New England fundamentalists. I too had ancestors whose lives had been spent in prayer and public service. Their voices “murmured in my blood” like rain-filled streams, ready to overflow. They told me that Life, not Art, was the true sphere of man. And woman? A woman who makes “images”? My grandmother would have mocked me with laughter, then narrowed her eyes in anger. What was I doing in this strange and Gentile city without my husband and my children? Why wasn’t I content to live God’s will? What was I trying to prove?

I was not trying to prove anything, I thought; I was trying to understand. I wanted to find a pattern—a way of living that would permit me to balance love and work without the scars of sacrifice. It was a personal journey, perhaps a selfish one, but if I could bring order to one woman’s life, wouldn’t my words and images serve others?

Anne Lindbergh was tired, she would later say, of “sugary images”

that made her appear “sweet and kind.” She was “a rebel,” she said with pride and anger. I began to realize that my task was to find the rebel beneath the saint, the steel beneath the porcelain—the psychological reality that obscured the myth.

My problems, however, would prove to be less esoteric. I had written no books, and I was not a historian. I was a housewife and a mother of three, with a fascination for Anne Lindbergh and a desire to write. Paradoxically, my lack of public reputation persuaded Mrs. Lindbergh to take me at my word. I had no past and I made no promise except my commitment to honest scholarship. In a period of two years, I cultivated relations with members of the family. It was clear that I had no political or ideological motives, and, for the moment at least, was welcomed as a friend. But as I met with Anne Lindbergh again and again, ten times in all, her advisers grew suspicious. Who was this “housewife” Susan Hertog? And what did she really want? Was she as earnest as she appeared to be, or was she part of a news media conspiracy? By the time Anne had her stroke, in 1991, many established writers were banging on her door, and, in the end, I was not given access to her unpublished papers. Nonetheless, I persevered.

The story, I realized, was mine for the taking, and it was more grand than any I might have imagined. To my advantage, Anne and Charles were writers. They wrote about everything to everybody. They had published diaries, articles, and books—travelogues, novels, memoirs, and poetry. I visited private and public archives and traveled throughout the United States and Europe to visit friends and relatives of the Morrow and Lindbergh families. But my most precious and telling moments were those spent with Anne.